Archives

Posts Tagged ‘dhsi’

June 20, 2014

New in the Neighbourhood

This year was my first ever experience of DHSI in Victoria, and it has been an awesome whirlwind of activities — meeting so many great people and participating in a lot of the colloquium and “Birds of a Feather” sessions. If I were to sum up the experience in a few words, it might be something like “excited conflict”. There is so much to see and do that it’s a little difficult not to become physically drained and mentally overloaded in just a couple days. Yet, at the end of the week, and even now, I find myself wanting to return for another heavy dose of the same, and wishing it was just a little bit longer.

The Course

I participated in The Sound of Digital Humanities course with Dr. John Barber, along with a few fellow colleagues I work with on a poetry archive project back at UBCO. Throughout the week, the course itself weaved through different focuses, and in between practicing basic editing in Audacity and GarageBand, there was much deep discussion about the nature of sound, theory, research, copyright, and the like. It is especially the latter discussion portion that I was keenly interested in, as we found that some others in the class were doing projects based on or around archives, and were tackling questions and concerns similar to what pertained to our project. It was an opportunity to not only listen and glean some greater insights from experts and generally brilliant minds, but to reciprocate it and impart some of my knowledge to others for application towards their own projects. The general atmosphere is… infectious enthusiasm: everyone is quick to offer their own valuable experiences and suggestions for solutions for others peoples’ projects — in some cases right down to the nitty-gritty technical details. In fact, come to think of it, it doesn’t stray too far from what you might find at a typical medium-sized gathering at a web development conference: some give talks on new cool techniques and technologies, and everyone is engaged in vigorous talk of theory and stories and jokes about working in the field, even over a couple pints at the pub. It was that kind of coming together and collaboration in our class (sans alcohol) which culminated with each of us putting a bit of ourselves into a sound collage representative of the broader aims of the Digital Humanities and our nuanced experiences in it. It was all at times (sometimes simultaneously) hilarious and poignant. Definitely not something I will forget any time soon.

New in the Neighbourhood

In addition to meeting new acquaintances, the week was also a time of reunion, where I was able to reconnect with my colleagues on our poetry archive project. It was a helpful and fun time for us to “regroup” — to reflect on the project’s progress, and also come back with new energy in thinking about ways of moving forward, with the application of some of our discussions both in class and within the larger DHSI hub.. For me, Chris Friend’s presentation on crowd-sourced content creation and collaborative tools yielded wonderful points about the benefits and perils of using such a model pedagogically. It has made me more particularly sensitive to how pedagogical functions might be brought to our archive, and what designs we might create (both visually and technically) to accommodate that.

On a more personal front, attending DHSI (and by extension, learning about the Digital Humanities as a field this year) has solidified a deep sense of belonging for me through moments of glorious serendipity, if you will; of happening upon something fascinating at the end of a long wandering; of searching for a place to call my “intellectual” and “academic” home. It is a place that beautifully brings together my major pursuits of web development, literary theory/criticism, and music, and collectively articulates them as the makeup of “what I do”. It has been one of those somewhat rare “Ah-ha!” moments where you find something that you were looking for all along, but didn’t know quite what it was.

It’s been a wild ride, but one that I definitely want embark on again. My greatest thank yous, all of my friends and colleagues — old and new — for such a wonderful experience. I look forward to when I can return again for another week-long adventure and “geekfest”!

Keep it “robust” my friends.

June 15, 2014

In My End is My Beginning

With the support of EMiC I have attended DHSI as a student from the very beginning and have learned an enormous amount – only part of my huge debt to EMiC over the years.

In the course of my years at DHSI, I believe I have set two precedents: I am the first person to have retired since joining EMiC and I am the first EMiCite to have graduated from the status of student to instructor.

Previous to teaching this year’s DHIS/DEMiC course I had taught TEMiC in Peterborough, but while that course dealt to some extent with digital editing its primary focus was editorial theory. The course this year grew out of a text/image tool for genetic editing which Josh and I are in the process of developing (see Chris Doody’s post, The Digital Page: Brazilian Journal ). The course did not focus on this tool, however: its focus was on the XSLT which is the backbone of the tool, and the collaborative process that went into developing it.

We had originally intended to call the course Every Batman Needs a Robin (a bow to another, very successful digital humanities collaboration involving Mike DiSanto and Robin Isard) but we soon realized that this would misrepresent the true nature of our non-hierarchical working relationship. We considered Every Batman Needs an Alfred but that seemed a bit esoteric.

Although Josh and I worked very closely together in planning the course, I was very much his assistant in teaching it, since his mastery of XSLT far exceeds mine. But this was a central thrust of the course. If digital humanists are to succeed in their projects, unless they are highly experienced programmers themselves – which few are, or have the time or inclination to become – it is necessary to establish a strong, personal, longstanding relationship with a developer. Our experience, and the experience of other digital humanist/developer teams, is that the project will take shape as a result of this collaboration, and the shape that it will take is often very different than what the digital humanist who initiated the project had in mind.

My role in the course was twofold: to help students out with the numerous hands-on exercises which we had devised for them (I wasn’t nearly as good at this as Josh) and to act as a kind of stand-in for the students, asking for clarification or repetition of points that were blindingly obvious to Josh but perhaps less so for the non-programmers amongst us. I was obviously much better at this than Josh was.

We had a very wide range of students in the course – from Master’s students to a Professor Emeritus – with a similarly wide range of projects, skills and aptitudes. But, judging by our interactions with the students and the student evaluations we struck a pretty good balance.

Certainly, from my point of view teaching such a committed and intelligent group of students who seem to have genuinely appreciated the work we put into the course, and doing so with my son (we didn’t fight once!) was a great experience – a real high point of my career and life.

I was very pleased to hear, then, that we have been asked to return with the course next year. So one of my many debts to EMiC, as it comes to its appointed end, is that my association with it has marked a new beginning for me – as a DHSI instructor.

June 12, 2014

What Makes It Work

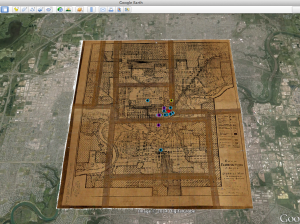

As part of EMiC at DHSI 2014, I took part in the Geographical Information Systems (GIS) course with Ian Gregory. The course was tutorial-based, with a set of progressive practical exercises that took the class through the creation of static map documents through plotting historical data and georeferencing archival maps into the visualization and exploration of information from literary texts and less concrete datasets.

I have been working with a range of material relating to Canadian radical manifestos, pamphlets, and periodicals as I try to reconstruct patterns of publication, circulation, and exchange. Recently, I have been looking at paratextual networks (connections shown in advertisements, subscription lists, newsagent stamps, or notices for allied organizations, for example) while trying to connect these to real-world locations and human occupation. For this course, I brought a small body of material relating to the 1932 Edmonton Hunger March: (1) an archival map of the City of Edmonton, 1933 (with great thanks to Mo Engel and the Pipelines project, as well as Virginia Pow, the Map Librarian at the University of Alberta, who very generously tracked down this document and scanned it on my behalf); (2) organizational details relating to the Canadian Labor Defense League, taken from a 1933 pamphlet, “The Alberta Hunger-March and the Trial of the Victims of Brownlee’s Police Terror”, including unique stamps and marks observed in five different copies held at various archives and library collections; (3) relief data, including locations of rooming houses and meals taken by single unemployed men, from the City Commissoner’s fonds at the City of Edmonton Archives; and (4) addresses and locational data for all booksellers, newspapers, and newsstands in Edmonton circa 1932-33, taken from the 1932 and 1933 Henderson’s Directories (held at the Provincial Archives of Alberta, as well as digitized in the Peel’s Prairie Provinces Collection).

Through the course of the week I was able to do the following:

1. Format my (address, linguistic) data into usable coordinate points.

2. Develop a working knowledge of the ArcGIS software program, which is available to me at the University of Alberta.

3. Plot map layers to distinguish organizations, meeting places, booksellers, and newspapers.

4. Georeference my archival map to bring it into line with real-world coordinates.

5. Layer my data over the map to create a flat document (useful as a handout or presentation image).

6. Export my map and all layers into Google Earth, where I can visualize the historical data on top of present-day Edmonton, as well as display and manipulate my map layers. (Unfortunately, the processed map is not as sharp as the original scan.)

7. Determine the next stages for adding relief data, surveillance data, and broadening these layers out beyond Edmonton.

Detail: Archival map of City of Edmonton, 1933. Downtown area showing CLDL (red), booksellers (purple), newsstands (blue), and meeting places (yellow)

What I mean to say is, it worked. IT WORKED! For the first time in five years, I came to DHSI with an idea and some data, learned the right skills well enough to put the idea into action, and to complete something immediately usable and still extensible.

This affords an excellent opportunity for reflecting on this process, as well as the work of many other DH projects. What makes it work? I have a few ideas:

1. Expectations. Previous courses, experiments, and failures have begun to give me a sense of the kind of data that is usable and the kind of outcomes that are possible in a short time. A small set of data, with a small outcome – a test, a proof, a starting place – seems to be most easily handled in the five short days of DHSI, and is a good practice for beginning larger projects.

2. Previous skills. Last year, I took Harvey Quamen’s excellent Databases course, which gave me a working knowledge of tables, queries, and overall data organization, which helped to make sense of the way GIS tools operated. Data-mining and visualization would be very useful for the GIS course as well.

3. Preparation. I came with a map in a high-resolution TIFF format, as well as a few tables of data pulled from the archive sources I listed above. I did the groundwork ahead of time; there is no time in a DHSI intensive to be fiddling with address look-ups or author attributions. Equally, good DH work is built on a deep foundation of research scholarship, pulling together information from many traditional methods and sources, then generating new questions and possibilities that plunge us back into the material. Good sources, and close knowledge of the material permit more complex and interesting questions.

4. Projections. Looking ahead to what you want to do next, or what more you want to add helps to stymie the frustration that can come with DH work, while also connecting your project to work in other areas, and adding momentum to those working on new tools and new approaches. “What do you want to do?” is always in tension with “What can you do now?” – but “now” is always a moving target.

5. Collaboration. I am wholly indebted to the work of other scholars, researchers (published and not), librarians, archivists, staff, students, and community members who have helped me to gather even the small set of data used here, and who have been asking the great questions and offering the great readings that I want to explore. The work I have detailed here is one throughline of the work always being done by many, many people. You do not work alone, you should not work alone, and if you are not acknowledging those who work with you, your scholarship is unsustainable and unethical.

While I continue to work through this project, and to hook it into other areas of research and collaboration, these are the points that I try to apply both to my research practices and politics. How will we continue to work with each other, and what makes it work best?

June 9, 2012

DH Tools and Proletarian Texts

(This post originally appeared on the Proletarian Literature and Arts blog.)

I’m at the Digital Humanities Summer Institute at the University of Victoria this week. I’m taking a course on the Pre-Digital Book, which is already generating lots of interesting ideas about how we think and work with material texts, and how that is changing as we move into screen-based lives. There are, of course, many implications for how these differing textual modes relate to how we study and teach proletarian material, and more importantly, how class bears on these relationships. I hope to share some of these ideas as they have developed for me over the week. The course has taken up these questions in relation to medieval manuscripts and early modern incunablua and print, but the issues at stake are relevant for modern material as well. The instructors and librarians were kind enough to bring in a 1929 “novel in woodcuts” by Lynd Ward for me to look at – more on that will follow.

But, for fun, I also wanted to post about a little analysis experiment I did with some textual analysis tools.

I used the Voyant analysis tool to examine a set of Canadian manifesto writing. I transcribed six texts either from previous print publications or from archival scans for use as the corpus. These included: (1) “Manifesto of the Communist Parties of the British Empire”; (2) Tim Buck, “Indictment of Capitalism”; (3) CCF, “Regina Manifesto”; (4) Florence Custance, “Women and the New Age”; (5) “Our Credentials” from the first issue of Masses; and (6) Relief Camp Workers Strike Committee, “Official Statement”. [The RCWSC document remains my favorite text of all time.] Once applied, the tools let me read the texts in new ways, pulling out information or confirming ideas that I had about them in meaningful ways. You can find the summary of my corpus here.

The simplest visualization is the Cirrus word cloud, which at a glance shows that these texts are absolutely dominated by the language of class and politics (unsurprising, as they are aimed at remaking the existing class order). Michael Denning’s statement in The Cultural Front that the language of the 1930s became “labored” in both the public and metaphoric spheres is clearly reflected in this image.

Cirrus visualization of Canadian manifesto texts

Cirrus visualization of Canadian manifesto texts

Looking at the differences among the materials, an analysis of distinctive words is a simple way to get at the position of a given text in relation to the others. We might think of these Canadian manifestos as occupying the same ground of debate (though they are not responding to one another directly), but not necessarily sharing the same tent. For example, the “Manifesto of the Communist Parties of the British Empire” shows a much higher concentration of the term “war”, which helps situate it to later in the 1930s. The “Regina Manifesto” is overwhelmingly concerned with the “public” as it plans for a collective society. Florence Custance’s feminist statement shows itself to be more unique in its own time, as it uses “women” and female pronouns far beyond the other texts. And the Masses text betrays its literary periodical background with its heavier use of “art”.

The density of vocabulary in the texts can tell us something about intended readerships, and purpose of the text. Masses plays with the linguistic conventions of the manifesto to develop a text that is both assertive and creative; accordingly, it uses the largest variety of words to do so. However, the RCWSC is not far behind in its forthright call to action, which tells me something interesting about the role of the imaginative mode in connecting revolution with creative acts. Buck’s “Indictment” is the least dense text. It’s also the longest, which makes for a highly repetitive text. The “Indictment” has a strong oral quality to it, commenting on Buck’s trial and defense and with response and Marxist analysis. It is also highly indebted to that style, parsing its terms minutely and using them for step-by-step explanations. It is in many ways the most didactic of the texts, as the word density suggests, though such analysis misses the purposeful element of the limited word choices. I find Buck’s repetition to have an incantatory quality connecting it more closely to spoken debate than the other texts, an impression that comes out of working with the text closely, while typing and re-typing, and reading it aloud for myself. Word density is not for me an assignation of value; rather, it is one of many ways of framing some thoughts on how these texts – and manifestos more broadly – employ particular rhetorical modes and how we can follow them through.

Here is the link to the Voyant analysis of my manifestos. I invite you to take a look, play around, and consider throwing up some text from other working-class and proletarian sources. It seems to me that a lot of textual analysis begins by reaching for “important” texts – those that are canonical, or historical. The tools make no distinction – I would like to see more examples of writing from below feeding into the ways we think about texts in the DH realm.

August 23, 2010

TEI & the bigger picture: an interview with Julia Flanders

I thought those of us who had been to DHSI and who were fortunate enough to take the TEI course with Julia Flanders and Syd Bauman might be interested in a recent interview with Julia, in which she puts the TEI Guidelines and the digital humanities into the wider context of scholarship, pedagogy and the direction of the humanities more generally. (I also thought others might be reassured, as I was, to see someone who is now one of the foremost authorities on TEI describing herself as being baffled by the technology when she first began as a graduate student with the Women Writers Project …)

Here are a few excerpts to give you a sense of the piece:

[on how her interest in DH developed] I think that the fundamental question I had in my mind had to do with how we can understand the relationship between the surfaces of things – how they make meaning and how they operate culturally, how cultural artefacts speak to us. And the sort of deeper questions about materiality and this artefactual nature of things: the structure of the aesthetic, the politics of the aesthetic; all of that had interested me for a while, and I didn’t immediately see the connections. But once I started working with what was then what would still be called humanities computing and with text encoding, I could suddenly see these longer-standing interests being revitalized or reformulated or something like that in a way that showed me that I hadn’t really made a departure. I was just taking up a new set of questions, a new set of ways of asking the same kinds of questions I’d been interested in all along.

I sometimes encounter a sense of resistance or suspicion when explaining the digital elements of my research, and this is such a good response to it: to point out that DH methodologies don’t erase considerations of materiality but rather can foreground them by offering new and provocative optics, and thereby force us to think about them, and how to represent them, with a set of tools and a vocabulary that we haven’t had to use before. Bart’s thoughts on versioning and hierarchies are one example of this; Vanessa’s on Project[ive] Verse are another.

[discussing how one might define DH] the digital humanities represents a kind of critical method. It’s an application of critical analysis to a set of digital methods. In other words, it’s not simply the deployment of technology in the study of humanities, but it’s an expressed interest in how the relationship between the surface and the method or the surface and the various technological underpinnings and back stories — how that relationship can be probed and understood and critiqued. And I think that that is the hallmark of the best work in digital humanities, that it carries with it a kind of self-reflective interest in what is happening both at a technological level – and it’s what is the effect of these digital methods on our practice – and also at a discursive level. In other words, what is happening to the rhetoric of scholarship as a result of these changes in the way we think of media and the ways that we express ourselves and the ways that we share and consume and store and interpret digital artefacts.

Again, I’m struck by the lucidity of this, perhaps because I’ve found myself having to do a fair bit of explaining of DH in recent weeks to people who, while they seem open to the idea of using technology to help push forward the frontiers of knowledge in the humanities, have had little, if any, exposure to the kind of methodological bewilderment that its use can entail. So the fact that a TEI digital edition, rather than being some kind of whizzy way to make bits of text pop up on the screen, is itself an embodiment of a kind of editorial transparency, is a very nice illustration.

[on the role of TEI within DH] the TEI also serves a more critical purpose which is to state and demonstrate the importance of methodological transparency in the creation of digital objects. So, what the TEI, not uniquely, but by its nature brings to digital humanities is the commitment to thinking through one’s digital methods and demonstrating them as methods, making them accessible to other people, exposing them to critique and to inquiry and to emulation. So, not hiding them inside of a black box but rather saying: look this, this encoding that I have done is an integral part of my representation of the text. And I think that the — I said that the TEI isn’t the only place to do that, but it models it interestingly, and it provides for it at a number of levels that I think are too detailed to go into here but are really worth studying and emulating.

I’d like to think that this is a good description of what we’re doing with the EMiC editions: exposing the texts, and our editorial treatement of them, to critique and to inquiry. In the case of my own project involving correspondence, this involves using the texts to look at the construction of the ideas of modernism and modernity. I also think the discussions we’ve begun to have as a group about how our editions might, and should, talk to each other (eg. by trying to agree on the meaning of particular tags, or by standardising the information that goes into our personographies) is part of the process of taking our own personal critical approaches out of the black box, and holding them up to the scrutiny of others.

The entire interview – in plain text, podcast and, of course, TEI format – can be found on the TEI website here.

June 28, 2010

Versioning Livesay’s “Spain”

G’Day Folks;

I hope you are all finding your way into summer mode since returning from UVic. I had my first lake swim of the summer on Friday afternoon. It was glorious.

I’ve not had a single sighting of a bunny since my return…I got used to them but now they are strange again. Ok; on to DEMiC things…

One of my main interests in approaching TEI and XML is how to present non-hierarchical versions of texts (mostly poems, I guess) within an explicitly hierarchical encoding structure. As a result, I am less interested at this point in the issues of explanatory mark-up and more interested in structural issues.

I figured that Dorothy Livesay’s poem “Spain” would work as a good text to play with and try out multiple methods of editing. After trying a couple of different things, I decided to work with a form of layered parallelisms: at the level of the poem as a whole; at the level of stanzas; and, at the level of the individual line. I took six different versions of the poem and included them all in my XML document:

<body>

<head corresp=”#spain”>Spain<lb></lb>by Dorothy Livesay</head>

<div xml:id=”nf” type=”poem”>

<head><emph rend=”italics”>New Frontier </emph>Version</head>

<lg type=”stanza” rhyme=”aabb”><lg subtype=”quatrain” xml:id=”nfs.01″>

<lb/><l xml:id=”nfl.01″>When the bare branch responds to leaf and <rhyme label=”a”>light</rhyme>,</l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”nfl.02″>Remember them! It is for this they <rhyme label=”a”>fight</rhyme>.</l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”nfl.03″>It is for hills uncoiling and the green <rhyme label=”b”>thrust</rhyme></l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”nfl.04″>Of spring, that they lie choked with battle <rhyme label=”b”>dust</rhyme>.</l></lg></lg>

<lg type=”stanza” rhyme=”aabb”><lg subtype=”quatrain” xml:id=”nfs.02″>

<lb/><l xml:id=”nfl.05″>You who hold beauty at your finger <rhyme label=”a”>tips</rhyme></l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”nfl.06″>Hold it, because the splintering gunshot <rhyme label=”a”>rips</rhyme></l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”nfl.07″>Between your comrades’ eyes: hold it, <rhyme label=”b”>across</rhyme></l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”nfl.08″>Their bodies’ barricade of blood and <rhyme label=”b”>loss</rhyme></l></lg></lg>

<lg type=”stanza” rhyme=”aabb”><lg subtype=”quatrain” xml:id=”nfs.03″>

<lb/><l xml:id=”nfl.09″>You who live quietly in sunlit <rhyme label=”a”>space</rhyme></l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”nfl.10″>Reading the <rs type= “newspaper”>Herald</rs> after morning <rhyme label=”a”>grace</rhyme>,</l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”nfl.11″>Can count peace dear, when it has <rhyme label=”b”>driven</rhyme></l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”nfl.12″>Your sons to struggle for this grim, new <rhyme label=”b”>heaven</rhyme>.</l></lg></lg>

</div>

<div xml:id=”mq” type=”poem”>

<head><emph rend=”italics”>Marxist Quarterly </emph>Version</head>

<lg type=”stanza” rhyme=”aabb”><lg subtype=”quatrain” xml:id=”mq.01″>

<lb/><l xml:id=”mql.01″>When the bare branch responds to leaf and <rhyme label=”a”>light</rhyme>,</l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”mql.02″>Remember them! It is for this they <rhyme label=”a”>fight</rhyme>.</l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”mql.03″>It is for hills uncoiling and the green <rhyme label=”b”>thrust</rhyme></l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”mql.04″>Of spring, that they lie choked with battle <rhyme label=”b”>dust</rhyme>.</l></lg></lg>

<lg type=”stanza” rhyme=”aabb”><lg subtype=”quatrain” xml:id=”mqs.02″>

<lb/><l xml:id=”mql.05″>You who hold beauty at your finger <rhyme label=”a”>tips</rhyme></l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”mql.06″>Hold it, because the splintering gunshot <rhyme label=”a”>rips</rhyme></l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”mql.07″>Between your comrades’ eyes: hold it, <rhyme label=”b”>across</rhyme></l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”mql.08″>Their bodies’ barricade of blood and <rhyme label=”b”>loss</rhyme></l></lg></lg>

<lg type=”stanza” rhyme=”aabb”><lg subtype=”quatrain” xml:id=”mqs.03″>

<lb/><l xml:id=”mql.09″>You who live quietly in sunlit <rhyme label=”a”>space</rhyme></l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”mql.10″>Reading the <rs type= “newspaper”><emph rend=”italics”>Herald</emph></rs> after morning <rhyme label=”a”>grace</rhyme>,</l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”mql.11″>Can count peace dear, when it has <rhyme label=”b”>driven</rhyme></l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”mql.12″>Your sons to struggle for this grim, new <rhyme label=”b”>heaven</rhyme>.</l></lg></lg>

</div>

<div xml:id=”cpts” type=”poem”>

<head><emph rend=”italics”>Collected Poems </emph>Version</head>

<lg type=”stanza” rhyme=”aabb”><lg subtype=”quatrain” xml:id=”cptss.01″>

<lb/><l xml:id=”cptsl.01″>When the bare branch responds to leaf and <rhyme label=”a”>light</rhyme></l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”cptsl.02″>Remember them: It is for this they <rhyme label=”a”>fight</rhyme>.</l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”cptsl.03″>It is for haze-swept hills and the green <rhyme label=”b”>thrust</rhyme></l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”cptsl.04″>Of pine, that they lie choked with battle <rhyme label=”b”>dust</rhyme>.</l></lg></lg>

<lg type=”stanza” rhyme=”aabb”><lg subtype=”quatrain” xml:id=”cptss.02″>

<lb/><l xml:id=”cptsl.05″>You who hold beauty at your finger-<rhyme label=”a”>tips</rhyme></l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”cptsl.06″>Hold it because the splintering gunshot <rhyme label=”a”>rips</rhyme></l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”cptsl.07″>Between your comrades’ eyes; hold it <rhyme label=”b”>across</rhyme></l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”cptsl.08″>Their bodies’ barricade of blood and <rhyme label=”b”>loss</rhyme>.</l></lg></lg>

<lg type=”stanza” rhyme=”aabb”><lg subtype=”quatrain” xml:id=”cptss.03″>

<lb/><l xml:id=”cptsl.09″>You who live quietly in sunlit <rhyme label=”a”>space</rhyme></l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”cptsl.10″>Reading The <rs type= “newspaper”>Herald</rs> after morning <rhyme label=”a”>grace</rhyme></l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”cptsl.11″>Can count peace dear, when it has <rhyme label=”b”>driven</rhyme></l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”cptsl.12″>Your sons to struggle for this grim, new <rhyme label=”b”>heaven</rhyme>.</l></lg></lg>

</div>

<div xml:id=”cvii” type=”poem”>

<head><emph rend=”italics”>CV/II </emph>Version</head>

<lg type=”stanza” rhyme=”aabb”><lg subtype=”quatrain” xml:id=”cviis.01″>

<lb/><l xml:id=”cviil.01″>When the bare branch responds to leaf and <rhyme label=”a”>light</rhyme>,</l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”cviil.02″>Remember them: It is for this they <rhyme label=”a”>fight</rhyme>.</l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”cviil.03″>It is for hills uncoiling and the green <rhyme label=”b”>thrust</rhyme></l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”cviil.04″>Of spring, that they lie choked with battle <rhyme label=”b”>dust</rhyme>.</l></lg></lg>

<lg type=”stanza” rhyme=”aabb”><lg subtype=”quatrain” xml:id=”cviis.02″>

<lb/><l xml:id=”cviil.05″>You who hold beauty at your finger-<rhyme label=”a”>tips</rhyme></l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”cviil.06″>Hold it because the splintering gunshot <rhyme label=”a”>rips</rhyme></l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”cviil.07″>Between your comrades’ eyes: hold it, <rhyme label=”b”>across</rhyme></l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”cviil.08″>Their bodies’ barricade of blood and <rhyme label=”b”>loss</rhyme>.</l></lg></lg>

<lg type=”stanza” subtype=”quatrain” rhyme=”aabb”><lg subtype=”quatrain” xml:id=”cviis.03″>

<lb/><l xml:id=”cviil.09″>You who live quietly in sunlit <rhyme label=”a”>space</rhyme></l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”cviil.10″>Reading the <rs type= “newspaper”>Herald</rs> after morning <rhyme label=”a”>grace</rhyme></l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”cviil.11″>Can count peace dear, if it has <rhyme label=”b”>driven</rhyme></l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”cviil.12″>Your sons to struggle for this grim, new <rhyme label=”b”>heaven</rhyme>.</l></lg></lg>

</div>

<div xml:id=”rmos” type=”poem”>

<head><emph rend=”italics”>Red Moon Over Spain </emph>Version</head>

<lg type=”stanza” rhyme=”aabb”><lg subtype=”quatrain” xml:id=”rmoss.01″>

<lb/><l xml:id=”rmosl.01″>When the bare branch responds to leaf and <rhyme label=”a”>light</rhyme>,</l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”rmosl.02″>Remember them! It is for this they <rhyme label=”a”>fight</rhyme>.</l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”rmosl.03″>It is for hills uncoiling and the green <rhyme label=”b”>thrust</rhyme></l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”rmosl.04″>Of spring, that they lie choked with battle <rhyme label=”b”>dust</rhyme>.</l></lg></lg>

<lg type=”stanza” rhyme=”aabb”><lg subtype=”quatrain” xml:id=”rmoss.02″>

<lb/><l xml:id=”rmosl.05″>You who hold beauty at your finger <rhyme label=”a”>tips</rhyme></l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”rmosl.06″>Hold it, because the splintering gunshot <rhyme label=”a”>rips</rhyme></l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”rmosl.07″>Between your comrades’ eyes: hold it, <rhyme label=”b”>across</rhyme></l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”rmosl.08″>Their bodies’ barricade of blood and <rhyme label=”b”>loss</rhyme>.</l></lg></lg>

<lg type=”stanza” rhyme=”aabb”><lg subtype=”quatrain” xml:id=”rmoss.03″>

<lb/><l xml:id=”rmosl.09″>You who live quietly in sunlit <rhyme label=”a”>space</rhyme></l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”rmosl.10″>Reading the <rs type= “newspaper”><emph rend=”italics”>Herald</emph></rs> after morning <rhyme label=”a”>grace</rhyme>,</l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”rmosl.11″>Can count peace dear, when it has <rhyme label=”b”>driven</rhyme></l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”rmosl.12″>Your sons to struggle for this grim new <rhyme label=”b”>heaven</rhyme>.</l></lg></lg>

</div>

<div xml:id=”sis” type=”poem”>

<head><emph rend=”italics”>Sealed in Struggle </emph>Version</head>

<lg type=”stanza” rhyme=”aabb”><lg subtype=”quatrain” xml:id=”siss.01″>

<lb/><l xml:id=”sisl.01″>When the bare branch responds to leaf and <rhyme label=”a”>light</rhyme></l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”sisl.02″>Remember them: It is for this they <rhyme label=”a”>fight</rhyme>.</l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”sisl.03″>It is for haze-swept hills and the green <rhyme label=”b”>thrust</rhyme></l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”sisl.04″>Of pine, that they lie choked with battle <rhyme label=”b”>dust</rhyme>.</l></lg></lg>

<lg type=”stanza” rhyme=”aabb”><lg subtype=”quatrain” xml:id=”siss.02″>

<lb/><l xml:id=”sisl.05″>You who hold beauty at your finger-<rhyme label=”a”>tips</rhyme></l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”sisl.06″>Hold it because the splintering gunshot <rhyme label=”a”>rips</rhyme></l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”sisl.07″>Between your comrades’ eyes; hold it <rhyme label=”b”>across</rhyme></l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”sisl.08″>Their bodies’ barricade of blood and <rhyme label=”b”>loss</rhyme>.</l></lg></lg>

<lg type=”stanza” rhyme=”aabb”><lg subtype=”quatrain” xml:id=”siss.03″>

<lb/><l xml:id=”sisl.09″>You who live quietly in sunlit <rhyme label=”a”>space</rhyme></l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”sisl.10″>Reading The <rs type= “newspaper”>Herald</rs> after morning <rhyme label=”a”>grace</rhyme>,</l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”sisl.11″>Can count peace dear, when it has <rhyme label=”b”>driven</rhyme></l>

<lb/><l xml:id=”sisl.12″>Your sons to struggle for this grim, new <rhyme label=”b”>heaven</rhyme>.</l></lg></lg>

</div>

</body>

In the back material I included some basic bibliographic material (which certainly needs to be beefed up) as well as a more complex set of link targets that allow for the parallel structure:

<listBibl>

<bibl corresp=”#nf”>

<author corresp=”#dorothylivesay”>Dorothy Livesay</author>

<title>New Fronier</title>

<date>1937</date>

</bibl>

<bibl corresp=”#mq”>

<author corresp=”#dorothylivesay”>Dorothy Livesay</author>

<title>Marxist Quarterly</title>

<date>1966</date>

</bibl>

<bibl corresp=”#cpts”>

<author corresp=”#dorothylivesay”>Dorothy Livesay</author>

<title>Collected Poems</title>

<date>1972</date>

</bibl>

<bibl corresp=”#cvii”>

<author corresp=”#dorothylivesay”>Dorothy Livesay</author>

<title>CV/II</title>

<date>1976</date>

</bibl>

<bibl corresp=”#rmos”>

<author corresp=”#dorothylivesay”>Dorothy Livesay</author>

<title>Red Moon Over Spain</title>

<date>1988</date>

</bibl>

<bibl corresp=”#sis” >

<author corresp=”#dorothylivesay”>Dorothy Livesay</author>

<title>Sealed in Struggle</title>

<date>1995</date>

</bibl>

</listBibl>

<div>

<linkGrp type=”alignment”>

<link targets=”#nf #mq #cpt #cvii #rmos #sis”/>

<link targets=”#nfs.01 #mqs.01 #cptss.01 #cviis.01 #rmoss.01 #siss.01″/>

<link targets=”#nfs.02 #mqs.02 #cptss.02 #cviis.02 #rmoss.02 #siss.02″/>

<link targets=”#nfs.03 #mqs.03 #cptss.03 #cviis.03 #rmoss.03 #siss.03″/>

<link targets=”#nfl.01 #mql.01 #cptsl.01 #cviil.01 #rmosl.01 #sisl.01″/>

<link targets=”#nfl.02 #mql.02 #cptsl.02 #cviil.02 #rmosl.02 #sisl.02″/>

<link targets=”#nfl.03 #mql.03 #cptsl.03 #cviil.03 #rmosl.03 #sisl.03″/>

<link targets=”#nfl.04 #mql.04 #cptsl.04 #cviil.04 #rmosl.04 #sisl.04″/>

<link targets=”#nfl.05 #mql.05 #cptsl.05 #cviil.05 #rmosl.05 #sisl.05″/>

<link targets=”#nfl.06 #mql.06 #cptsl.06 #cviil.06 #rmosl.06 #sisl.06″/>

<link targets=”#nfl.07 #mql.07 #cptsl.07 #cviil.07 #rmosl.07 #sisl.07″/>

<link targets=”#nfl.08 #mql.08 #cptsl.08 #cviil.08 #rmosl.08 #sisl.08″/>

<link targets=”#nfl.09 #mql.09 #cptsl.09 #cviil.09 #rmosl.09 #sisl.09″/>

<link targets=”#nfl.10 #mql.10 #cptsl.10 #cviil.10 #rmosl.10 #sisl.10″/>

<link targets=”#nfl.11 #mql.11 #cptsl.11 #cviil.11 #rmosl.11 #sisl.11″/>

<link targets=”#nfl.12 #mql.12 #cptsl.12 #cviil.12 #rmosl.12 #sisl.12″/>

</linkGrp>

</div>

“s” stands for stanza and “l” stands for line within the “link targets”

Although not written into the XML file, this parallel structure allows for the POTENTIAL versioning of the poem within a web-based interface. In other words, I think I am creating a non-hierarchical BASE for future application. As I said, I THINK I am creating a non-hierarchical BASE… am I?

June 9, 2010

The Reflex

I’ve been discovering this week at DHSI that I don’t really know what I talk about when I talk about digital humanism. As someone who also talks about modernism, and Canadian modernism, and labour, and print, this fogginess is nothing new. It might even be productive.

The tools we are encountering, and the ways in which we work through them, are restructuring the ways we think about text, and place, and time. Our conversations about the digital realm and the boundaries of our various disciplines are a key part of relating to these very technical concepts and grappling with the future we are propelled toward. But we’re also talking about the way we relate to modernity and how the issues we are confronting right now are also a way of reaching through to the earlier moment that we have taken up as modernists.

I have been considering the ways in which modernist print betrays anxieties about modernity through reflexive styles of rhetoric and form. Giddens has discussed how modern self-conceptions depend on constantly ordering and re-ordering social relations to accommodate continual knowledge input. It is a process of selection and shaping – not determinism; the modern actor is self-defined and highly conscious of the world around her. I’ve been considering the conversations floating around DHSI, and our own para-conversations here and elsewhere, as part of a reflexive field. As a researcher, I have to redefine myself and my position constantly to account for new tools and approaches. As a reader, I begin to connect texts and ideas in ways I was blind to before. As a conscious actor, I have to try to filter through a world of potential to find what has meaning to me and what fits to who I am. The reflex, as I experience it, is about redefining oneself as much as it is about kickback. It’s destabilizing, and exhilarating.

Vanessa’s post reflecting on the ways TEI’s structures work to enforce typographic codes, even as these codes were challenged by many modernist writers, shows so much insight into the way our tools can force us to re-think our texts – or to reify what was once revolutionary. I want to consider our conversations in the same way. I become absorbed in the intensity of a good conversation, and have had a few already. I am an inveterate gesturer. Pub stools make for good conversational bases. I want our conversations to flow back and forth from screen to stool and back again with fluid boundaries. I will do my best this week to seek out more voices and challenge more of my thoughts on these tools and approaches. I invite you to join me (and to try to convince me about Twitter…)!

June 9, 2010

EMiC @ DHSI in pictures

Emily, Chris et. al. were gracious enough to welcome us into their home-away-from-home for a little get-together this evening at DHSI. Fun was had – there’s photographic evidence:

June 9, 2010

Since we are fantasizing…

The really engaged posts on the EMiC blog have really got me thinking… If we put all this effort into developing the “EMiC” brand of digital mark-up… Would it be possible to create an online graduate journal, or something similar, within which we could publish samples of our projects? Hosted through EMiC, or partnered with EMiC, but a distinct entity?

This way, like Chris suggests, we could develop a “house style” which all our projects could conform to, but also use and develop.

It could be a collaboration, by both humanities scholars, digital humanists and other computer scientists. If we worked with them to develop the tools we’d need to start out and get the ball rolling, then we would be able to self teach through forums like the DHSI summer course.

Some of the small projects we might be interested in pursuing don’t necessarily have a forum for publication. This would give graduate students a chance to learn new technology, and then have an immediate application for it. They would know that their work had a possible “home” within the journal.

Obviously this is looking a little bit longer term, but it would be really amazing if we were able to lay the groundwork for this in the next few years, while we have an EMiC to support and engage us.

Perhaps it could be split into two parts, half scholarly articles about editing in print and online, and half documents or editorial projects that are entirely born digital.

I realize that I am perhaps being a bit over ambitious… But I couldn’t help but take it to the next level. Thoughts??

Did I take it too far?

Did I?

June 8, 2010

Thoughts so far on TEI

After two days of TEI fundamentals, I have come to a few conclusions.

First, the most interesting thing about TEI is not the things that you can do, but the things that you cannot do. TEI is, as far as I understand it, only concerned with the content of the text, ignoring everything else (paratextual elements, marginalia, interesting layout, etc.) – stuff some of us find extremely valuable. On top of this, the coding for variants is messy, complicated, and would be next to impossible for complicated variants. For an example of TEI markup for variants, check out: http://www.wwp.brown.edu/encoding/workshops/uvic2010/presentations/html/advanced_markup_09.xhtml.

As a result, I am glad that EMiC is developing an excellent IMT – this should solve many of the limitations of TEI, at least from my perspective.

Finally, while participants can all learn basic TEI and encoding, the next step of course would be to establish a CSS stylesheet. It seems to me that EMiC, like all publishing houses, should establish a single organization style, and design a stylesheet that all EMiC participants are free to use. This would ensure a consistent design and look of all EMiC orientated projects in their digital form. Maybe this could be something discussed at a roundtable at next-years speculated EMiC orientated course at DHSI.

Something to ponder.