Archives

Archive for March, 2015

March 31, 2015

Community and Precarity

“Also, happy last day of EMiC.”

This message just appeared on a Facebook chat I’m having with three other EMiCites, as we discuss exactly how much social time we can fit into the upcoming Digital Diversity conference in Edmonton. Many of us are not attending DHSI this year — our normal summer meet-up spot — and so we’re treating DigDiv as a mini reunion.

It’s not really the last day of EMiC. A simple fiscal end-date will not spell the end of the projects and collaborations we began over the past seven years, many of which will continue in various forms and reverberate through our institutions and disciplines.

I have benefitted from tremendous research and training opportunities through my affiliation with EMiC. Since the first day that co-applicant Paul Hjartarson invited me, an utterly overwhelmed new MA student, for a coffee in HUB mall at the U of A and asked if I’d be interested in joining a project that would send me to Victoria to learn something about computers, EMiC has shaped my academic trajectory. The connections I made in that first year led directly to my current position as a SSHRC-funded postdoctoral fellow, back at the U of A and working with Paul again, now with five DHSIs under my belt and a somewhat more robust sense of what computers do. I am hugely grateful for having been in the right place at the right time.

But what I will value, more than the conferences and seminars and publications, is the community.

It will be news to absolutely no one that it’s a scary time to be an emerging academic right now. The discourse is positively apocalyptic. Many of us are leaving academia altogether, seeking out rewarding careers in different fields. Others hold on, trying to stay committed to the values of our teaching and research while experiencing the real costs of our precarity. I don’t use the word precarity lightly — we should never forget that our “shared precariouness” is not shared equally — but I use it here to underline how powerful communities can be in the face of this affective burden.

Professional opportunities can help to pave the way to exciting careers. Interdisciplinary and multi-institutional collaborations produce innovation and new knowledge. But communities preserve and support us; they give us perspective on what really matters, back us in our struggles, keep us sane and human in the face of systems that threaten to break us down.

I often talk about the collaborations that make my work possible, but I rarely talk about the communities that make it possible for me to do my work. As important as the days spent in DHSI courses, struggling with TEI and databases, were the nights at karaoke bars, bonding over nostalgic 90s alt-rock. And while I can’t say where my career will take me in the next five or ten or twenty years, I take comfort in knowing that I’ll always have a bunch of nerds to make #canlit jokes with me.

March 31, 2015

The Dove and the DH Guru of Indiana: The Carl Watts Story

It’s hard to believe that it’s been almost a year since I was given the go-ahead to begin my digital edition of Laura Goodman Salverson’s The Dove. When I got this opportunity, I knew very little about the Digital Humanities. It often feels like this is still the case; nevertheless, in the past year I’ve attained some practical skills, made some new CanLit discoveries, and embarked on a mission to help people who also feel incompetent as they take their first steps in the world of DH.

Although I had for some time been thinking about the relevance (or at least peculiarity) of The Dove, last spring I was suddenly overwhelmed with practical questions that needed answering. Scanning pages was easy enough, but some other basic steps were bound up with a slew of large and poorly formed queries: Is this the Tesseract I’ve heard about? How do I make it work? Can a lone man indeed create a digital edition on his laptop? Where does it go? During those early days in Kingston it seemed like there was nowhere to turn.

With the help of two fabulous colleagues (Google and Emily Murphy), however, I was eventually able to crack the code. The first colleague taught me how to generate reams of .txt files in which each gross stain on the pages of the novel was transcribed as a * or a Q. The second colleague solved my schema problem and pointed out some errors I had made in my TEI markup. This eleventh-hour save notwithstanding, I would describe myself as a master of DIY TEI. And while my basic TEI/XML markup is functional, my CSS skills are currently both DIY and LOL.

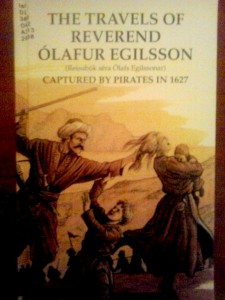

As I’ve been messing around with CSS, I’ve also continued researching the text’s history. I’ve always felt strange using the word “research” to describe my academic work; all this word ever really meant to me (as a graduate student) was frantically reading articles and then synthesizing them into either a term paper or an attempted publication. In contrast, having an entire funded year to read around a topic allowed me to make some actual discoveries. For instance, on my trip to view the typescript of the novel at Library and Archives Canada, I learned that Salverson made corrections with a green pen and that government employees enjoy eating lunch in food courts. As far as The Dove is concerned, I managed to uncover a consistent error in the small amount of writing that has mentioned the novel. These sources usually describe the text as based on an Icelandic saga, but my readings in this area revealed that this word usually refers to other, much earlier sources. Meanwhile, Salverson seems to have based her novel on one particular, somewhat different text: a seventeenth-century memoir entitled The Travels of Reverend Ólafur Egilsson. Much of the background research that led to this discovery has found its way into my introduction to the edition. This introduction is only about half finished, but when I mutter things to myself I definitely describe it as “masterful.” In the meantime, I’ll leave you with a picture of the memoir, which was conveniently translated into English for the first time in 2008:

I’m also fresh off delivering a grotesque Frankenstein’s Monster of a conference presentation at the annual meeting of the College English Association in Indianapolis. I started by describing my edition and discoveries, moved on to some practical tips regarding getting a digital-editing project off the ground, and concluded with a state-of-the-discipline rumination on textual communities and critical contexts in our early- or mid-DH epoch. Some audience members looked bewildered (in one case, disgusted), but when the session ended I was greeted by a lineup of people who either had technical questions of their own or were offering their thanks for being provided with a basic plan for getting started on a similar project. After having spent my early days struggling to answer such basic questions, I felt good knowing that I was now able to help people in similar situations. Perhaps some of the horrified looks I got during the presentation were merely reactions to the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, which was passed just as I arrived in the city. On that note, I took this picture of the Indiana Death Star shortly after I dubbed myself the DH Guru of the state:

As I move on to the next stages of the project, I want to thank Glenn Willmott, Emily Murphy, and Google for their advice. Also, obviously, a big thank you goes out to Dean and EMiC for allowing me to make progress on the edition and encouraging me to share my research and experiences.

March 27, 2015

Legends of Vancouver: Collaborative Learning (and Putting Ethics into Practice)

Greetings, EMiC community!

At nearly two semesters into my PhD at Simon Fraser University, I have some exciting research updates to share. For the 2014-15 year, my EMiC PhD Stipend project proposed to analyze and digitize E. Pauline Johnson and Chief Capilano’s Legends of Vancouver (first published in 1911).

My stipend project began with many, many hours spent in SFU’s Special Collections library. With more than 50 copies of Legends in its holdings, SFU boasts an impressive collection that spans over a century of publication.

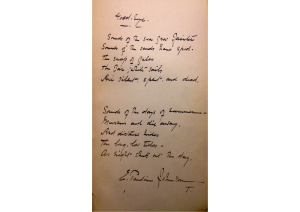

One of the most interesting parts of my research thus far has been investigating unique inscriptions and markings found in earlier copies; these paratextual elements situate Legends as a site for both remembrance and memorialization. In earlier editions of the text (those published between 1911 and 1913, while Johnson was still alive), some copies contain additional inscriptions penned by Johnson herself. In one case, Johnson makes the poignant exchange of the poem “Goodbye” as compensatory for the book’s shoddy construction: “this book seems to be rather badly put together so – I have written out a poem on the back flyleaf to ‘even things up’ – EPJ”.

In this poem, Johnson alludes to the passage from day into night as a metaphor for the transition from life into death. Her decision to inscribe this poem in 1912, only months before her eventual death from breast cancer, is curious. The poem is also significant in regards to the idea of loss – particularly as an expression of cultural mourning.

While comparing and analyzing the variant copies of Legends, I became interested in the changing paratextual apparatus and the ways in which it evinces an ongoing political and ideological series of recoveries and losses – specifically relating to Chief Capilano. Since this text was produced during the height of the socio-political movement of salvage ethnography (whereby Indigenous peoples were deemed to be on the brink of extinction), traces of these colonial power relations are present in the book’s paratext. With this anthropological trend, imbalanced power relations prevailed, often privileging the non-Indigenous voice and overshadowing the contributions of Indigenous collaborators. Early editions of this book speak to this imbalance in power, beginning with the front cover – while the generalized image of a male Chief (adorned with what appears to be Plains Indian regalia) is depicted, only Johnson’s name is listed as author. There is no mention of her collaborator on the title page, nor in the “Biographical Notice” section – and this process of erasure was perpetuated with subsequent editions. More contemporary versions of this text now include additional material about Johnson, but Capilano’s presence is still comparatively scarce (and to date, I have not seen a single edition of Legends that includes his photograph).

These observations bring me to my current research question: Why, in regards to this text, has Chief Capilano not been given the same kind of recognition as Pauline Johnson?

I am currently working in collaboration with members of the Coast Salish community to learn more about their perspectives on the Legends text. My hope is that by encouraging community dialogue and involving the descendants of Chief Capilano in this process, I can do my part to balance out the historical record. While this shift in focus strays from my initial goal of producing a digital edition, I believe that involving the community in this conversation first is necessary. After all, these are their stories.

Recently, I’ve had the opportunity to take part in an interdisciplinary colloquium and speaker series at SFU titled “Protecting Indigenous Cultural Heritage: Emergent Policy and Practice”. This series focuses on presenting new approaches to collaborative research and Indigenous policy development. As a non-Indigenous scholar working in the field of First Nations studies, this series has provided me with immeasurable insight as to best protocols for ensuring respectful collaboration. Most importantly, I’ve learned the value and necessity of putting ethics into practice. This means that my research may take more time – but I’ll be satisfied knowing that my research practices align with and reflect contemporary values regarding the protection of tangible and intangible Indigenous cultural heritage.

I would like to thank EMiC, and Dean, for giving me the opportunity to pursue this research.

March 24, 2015

Modernism Will Truly Never be the Same

By Glenn Willmott

As spring approaches, and eight years of EMiC’s flourishing, I think it’s reasonable to wonder if EMiC has not been the most widely and deeply productive collaborative literary project in Canada. No doubt, really. But there’s one thing that must stand out above all: the truly extraordinary devotion, creativity, and love of literature in the generations of present and past students who have made EMiC what it is. I am immensely appreciative of Dean, for having started it all, and kept it going, and to all those senior scholars who played their parts in research projects large and small. But to all those who are or have been student members of EMiC, I want to express my gratitude and admiration. Modernism will truly never be the same. In the right sense

March 18, 2015

A Journey to Naramata: Uncovering the work of Carroll Aikins and Canada’s “First” National Theatre

Given that I am barricaded at home during yet another snow day in Nova Scotia, I feel it is only fitting to write a blog post on summer productivity as some sort of ode to warmer weather. This summer, after an enriching week with Karis Shearer at UBC Okanagan’s TEMiC, I drove to Naramata as a pilgrimage to the location of Carroll Aikins’s Home Theatre—a theatre built above a fruit packing and storage facility in 1920 that was devoted to training Canadian actors.

I have been researching Aikins in large part because of the uniqueness of his play The God of Gods, which premiered in Birmingham, England in 1919 to the praise of theatre critics. The God of Gods seems to be the little play that could: it enjoyed a second mounting at Birmingham Repertory Theatre in 1921, came to Toronto’s Hart House Theatre for their 1922-23 season, then was produced in London, England in 1931. The play’s success abroad is by no means its only notable element; it is also a modernist play that engages in primitivism, anti-war sentiments, Nietzschean philosophy, and theosophy. And while Aikins is little know in today’s theatre circles, this seems to be far from true for many of the people in Naramata (even if the street signs offer variant spellings of his name).

Naramata’s Heritage Museum welcomed me with open arms; the elders regaled me with stories of the Aikins family, shared relevant local histories, and offered valuable resources (books, photographs, contact information for surviving Aikins family members). Craig Henderson, in particular, was incredibly helpful and acted as a tour guide, taking me to Aikins’s old home, Aikins’s Loop (where the building that housed the Home theatre can be found), and the remains of the Home Theatre. I have kept in touch with Henderson and he is hoping to produce one of Aikins’s other plays in the near future—a potential venture that nicely integrates my experience at TEMiC and DEMiC with my work on Aikins because a recording of a production of one of Aikins’s plays would make for an excellent online teaching or research tool.

Interviews with local historians and theatre practitioners helped to explain many of the allusions to historical figures and local folklore in Aikins’s plays. This trip solidified the value and necessity of qualitative research for my field—theatre, after all, occurs off the page and it is only in meeting with artists and visiting the homeland of Aikins and his Home Theatre that The God of Gods becomes a living piece of art.

(By Kailin Wright)