Archives

Archive for the ‘Training’ Category

June 12, 2014

What Makes It Work

As part of EMiC at DHSI 2014, I took part in the Geographical Information Systems (GIS) course with Ian Gregory. The course was tutorial-based, with a set of progressive practical exercises that took the class through the creation of static map documents through plotting historical data and georeferencing archival maps into the visualization and exploration of information from literary texts and less concrete datasets.

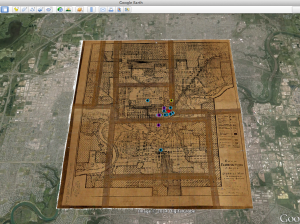

I have been working with a range of material relating to Canadian radical manifestos, pamphlets, and periodicals as I try to reconstruct patterns of publication, circulation, and exchange. Recently, I have been looking at paratextual networks (connections shown in advertisements, subscription lists, newsagent stamps, or notices for allied organizations, for example) while trying to connect these to real-world locations and human occupation. For this course, I brought a small body of material relating to the 1932 Edmonton Hunger March: (1) an archival map of the City of Edmonton, 1933 (with great thanks to Mo Engel and the Pipelines project, as well as Virginia Pow, the Map Librarian at the University of Alberta, who very generously tracked down this document and scanned it on my behalf); (2) organizational details relating to the Canadian Labor Defense League, taken from a 1933 pamphlet, “The Alberta Hunger-March and the Trial of the Victims of Brownlee’s Police Terror”, including unique stamps and marks observed in five different copies held at various archives and library collections; (3) relief data, including locations of rooming houses and meals taken by single unemployed men, from the City Commissoner’s fonds at the City of Edmonton Archives; and (4) addresses and locational data for all booksellers, newspapers, and newsstands in Edmonton circa 1932-33, taken from the 1932 and 1933 Henderson’s Directories (held at the Provincial Archives of Alberta, as well as digitized in the Peel’s Prairie Provinces Collection).

Through the course of the week I was able to do the following:

1. Format my (address, linguistic) data into usable coordinate points.

2. Develop a working knowledge of the ArcGIS software program, which is available to me at the University of Alberta.

3. Plot map layers to distinguish organizations, meeting places, booksellers, and newspapers.

4. Georeference my archival map to bring it into line with real-world coordinates.

5. Layer my data over the map to create a flat document (useful as a handout or presentation image).

6. Export my map and all layers into Google Earth, where I can visualize the historical data on top of present-day Edmonton, as well as display and manipulate my map layers. (Unfortunately, the processed map is not as sharp as the original scan.)

7. Determine the next stages for adding relief data, surveillance data, and broadening these layers out beyond Edmonton.

Detail: Archival map of City of Edmonton, 1933. Downtown area showing CLDL (red), booksellers (purple), newsstands (blue), and meeting places (yellow)

What I mean to say is, it worked. IT WORKED! For the first time in five years, I came to DHSI with an idea and some data, learned the right skills well enough to put the idea into action, and to complete something immediately usable and still extensible.

This affords an excellent opportunity for reflecting on this process, as well as the work of many other DH projects. What makes it work? I have a few ideas:

1. Expectations. Previous courses, experiments, and failures have begun to give me a sense of the kind of data that is usable and the kind of outcomes that are possible in a short time. A small set of data, with a small outcome – a test, a proof, a starting place – seems to be most easily handled in the five short days of DHSI, and is a good practice for beginning larger projects.

2. Previous skills. Last year, I took Harvey Quamen’s excellent Databases course, which gave me a working knowledge of tables, queries, and overall data organization, which helped to make sense of the way GIS tools operated. Data-mining and visualization would be very useful for the GIS course as well.

3. Preparation. I came with a map in a high-resolution TIFF format, as well as a few tables of data pulled from the archive sources I listed above. I did the groundwork ahead of time; there is no time in a DHSI intensive to be fiddling with address look-ups or author attributions. Equally, good DH work is built on a deep foundation of research scholarship, pulling together information from many traditional methods and sources, then generating new questions and possibilities that plunge us back into the material. Good sources, and close knowledge of the material permit more complex and interesting questions.

4. Projections. Looking ahead to what you want to do next, or what more you want to add helps to stymie the frustration that can come with DH work, while also connecting your project to work in other areas, and adding momentum to those working on new tools and new approaches. “What do you want to do?” is always in tension with “What can you do now?” – but “now” is always a moving target.

5. Collaboration. I am wholly indebted to the work of other scholars, researchers (published and not), librarians, archivists, staff, students, and community members who have helped me to gather even the small set of data used here, and who have been asking the great questions and offering the great readings that I want to explore. The work I have detailed here is one throughline of the work always being done by many, many people. You do not work alone, you should not work alone, and if you are not acknowledging those who work with you, your scholarship is unsustainable and unethical.

While I continue to work through this project, and to hook it into other areas of research and collaboration, these are the points that I try to apply both to my research practices and politics. How will we continue to work with each other, and what makes it work best?

June 12, 2014

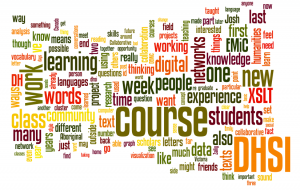

DHSI Word Cloud: The future is collaborative

This word cloud was created by submitting all of the EMiC blog posts about DHSI 2014 to a program that generates a visualization of the most commonly used words and phrases. Words that encourage working together, such as “community,” “cluster,” “collaborative,” “together,” and “social,” are a prominent theme in the cloud, with “Future Around Collaborative” acting as a fitting subtitle to the central words “Learning Course DHSI.” I also enjoy how the cloud arrangement created the term “Working Digital People.” Hopefully DHSI 2014 left everyone feeling like well-oiled working digital (humanities) people. The blog certainly indicates that everyone is feeling better equipped to create and motivated to co-create with others. Please keep sharing– the blog activity has been excellent these past ten days and the posts are encouraging and stimulating. Thanks to everyone for keeping the conversation going!

June 10, 2014

Community Formation – DEMiC 2014

Now that I am home unwinding from what was such an incredible and busy week, I can finally speak about my experience at this year’s DEMiC. This was my first time at DHSI, but it was not my first course through EMiC. Last summer I attended TEMiC in Kelowna where I had the opportunity to learn about different theoretical approaches to editorial work. The course was very useful to orient the beginnings of my editorial project, and for this reason I was eager to attend DEMiC. Although it differed from the course I did last summer, it did not disappoint. I had the opportunity to gain valuable hands-on experience with computer coding by working closely with fellow EMiC students and teachers Zaillig and Josh Pollock in the “A Collaborative Approach to XSLT” course. Following the completion of a challenging but useful week of training, I now come away with a strong foundation in XSLT that will be invaluable to the future of my editorial project, and feel as though I am part of a strong and close community.

Last week’s course promoted exactly what its name proposes: a collaborative approach to XSLT working through the interests of computer coding and literary scholarship. While the course demanded a lot of hard work, it was very well organized which enabled a manageable workload. Josh helped students learn the fundamentals of XSLT, and Zaillig provided his own feedback on the challenges he faced while working with this type of coding on his P.K. Page digital project. In addition, both Pollocks worked together to give insight into multiple possible ways of incorporating XSLT into digital editorial projects and also emphasized the importance of working in teams to generate new ideas. Although I was intimidated at first by the course due to my lack of familiarity with XSLT, both teachers were very patient and open to questions, and for this reason they created a very comfortable learning atmosphere. I was also able to consult other students in the class for guidance, as they were willing to help me work through any kinks I faced throughout the course. It was evident that the sense of collaboration that Zaillig and Josh tried to foster was not limited to their charismatic relationship, but also extended to their interaction with the class and the interaction they encouraged between the students. Albeit I will have to continue working diligently on becoming more comfortable with this new coding language; however, I feel as though the Pollock team has left me with the necessary tools to do so. I would recommend the course to anybody interested in doing digital editorial work, and/or interested in exploring new coding languages in a comfortable and productive learning environment.

Not only was the course a great collaborative learning experience, but I also enjoyed the opportunity to meet many EMiCers outside of class, and catching up with people I met at last year’s TEMiC. I come away from this experience not only feeling more comfortable with the concept of creating a digital project, but also as though I am part of a close community that is very supportive of its members. While I am sad that this was the last time DEMiC will happen, I am happy to have met so many interesting individuals, and to have learned from them. The course has only heightened my excitement for TEMiC next month where I will have the opportunity to gain more theoretical knowledge on sound archiving, and where I will be rejoining my fellow EMiC friends. For those who will be at TEMiC next month, see you soon! For the others, I look forward to crossing paths with you sometime soon!

June 7, 2014

DHSI and the Never-Ending Learning Curve of the Digital Humanities

As I sat through a course on GIS this week, learning theories of cartography and the intricacies of software, perhaps my largest takeaway was a reaffirmation of how different a field the digital humanities really is. On Monday 24 students entered the room with wildly varied backgrounds and levels of experience. Some had never forayed into digital research before; others had been teaching DH courses for years. Regardless of their starting point, however, by Friday all had substantially increased their knowledge and some incredible historical and literary mapping projects were already underway. In combination, the universal success of these populations suggests a truth about the digital humanities: the bar to entry is comparatively low, but you are never done learning.

Even more than the end products of this course, the questions that arose throughout the week were indicative of this fact. Questions like: ‘what constitutes data?’, ‘can location names be pulled from a text file automatically?’, ‘how does a database work?’, ‘what are the options for incorporating multimedia into the interface?’, ‘how can I share my work online?’, and ‘does imposing a literal geography change the source information?’. This mix of theoretical and practical queries, the answers to which were largely beyond the scope of a one-week course, stress the need for collaboration and a continual advancement of skills, two core components of digital humanities research. We are in a field where there is already too much to know and technology is ever advancing; keeping up on what you should be learning and who can provide the skills you lack is vital to pursuing progressive research.

The importance of DHSI for supporting scholars in this way is fairly clear. Few of us are in a position to commit to a full-term course, even if we live near a university that has some, but a weeklong intensive is manageable. For many courses, including the GIS one I had the chance to take, it also means being taught by a genuine expert in their area. Perhaps most significant, though, is the scale of the event and the opportunities it offers to network with some 600 fellow students and instructors. These interactions foster cooperative projects and inspire new ideas that might otherwise never arise. For all these reasons this week has taught me just how fundamental DHSI is to digital humanities in Canada and beyond. I was thrilled to be a part of it, and hope that I can join the ranks of annual attendees.

June 5, 2014

Visualizing the Landscape of Aboriginal Languages

I have spent the last few days in Scott Weingart’s class (scottbot.net) on Data, Math, Visualization, and Interpretation of Networks. We’ve been working on the basics of network analysis and learning some new lingo around networks and visualizations, such as nodes, vertexes, degrees, directed and undirected, weighted and unweighted edges. The tools we have being using, and the questions and discussions that have arisen in the class have been both practical and critical of the concept of network analysis, possible data bias, and semantic generalization. Nevertheless, we’ve forged on in our quest to create the most beautiful, eye-catching visualizations, and have I been able to see the possibilities in reading data differently through network visualization, and have a wider perspective on the concept of networks in general.

I came to the class without a particular project in mind, so once we started working on NodeXL, and I needed to insert data sets into the program, I sought out some data on the statscan site that I thought might be useful to interpret in relation to networks. I found some data related to Aboriginal languages in Canada from a study produced in 2011 and published in 2013: Aboriginal Languages in Canada. As the title of the table suggests, the data represents three main “nodes” – language, province, and concentration of population with regards to peoples with Aboriginal languages as a mother tongue. Although incomplete, the table does offer the possibility to map the data as a network across geopolitical borders to see where language groups could possibly meet at the edges. Here is the graph that was produced using the data from the survey:

The main nodes on the graph are the different Aboriginal languages, and the provinces in which they can be found as of 2011. It is a directed graph, which simply means that the language nodes point to the different provinces to which they are connected by an arrow pointing in the direction of their presence. Some of the languages only point to one province, while others point to multiple provinces. The edges of the graph, the arrows themselves, indicate the population size of those that speak the language in relation to their concentration in the particular province to which the edge points. The graph offers a few possible readings, and a number of problems. It cannot really tell us anything about the historical relationship between the different languages because it is based on data compiled in 2011 about people living with a particular nation-state constructed through colonial practices. It tells us nothing about the linguistic relationship between or amongst the various languages, although it is possible to see that the concentration of Cree and Algonquian-speaking peoples could possibly have linguistic similarities due to their proximity (which is true, but not expressed by the graph specifically).

What the graph does tell us, which might not be made clear simply by reading the data table, is that there are in fact three networks of Aboriginal languages as expressed in the data. The largest network stretches geographically from Quebec to Alberta to the Northwest Territories. On either side, we get two distinct networks of Aboriginal languages that are isolated along the Atlantic and the Pacific. It is possible to read this visualization of the data beyond the numbers – or at least ask some questions about what it is showing us. Why exactly do the coastal nations exist in isolated spaces? Is it possible to argue that coastal dwellers had different social practices that made them less likely to travel far from the coast, and thus have less interaction with other groups? Does the topography of the landscape have an effect on the fact that Northwest Coast First Nations languages do not cross over into Alberta as of 2011? Or is it simply that the data is insufficient, and we are only able to see how colonial practices produced these isolated networks of linguistic speakers through forced assimilation and the reservation system? I’d be interested to hear what anyone thinks about the visualization, and if there are others questions that could be asked by looking at the networks of Aboriginal languages in Canada. Happy DHSI to all!

June 2, 2014

#DHSI2014 – All the Things, All the People

Day 1 for #dhsi2014 is overwhelming. You want to see and meet all the people you know (or admire from afar) through social media, reunite with old friends, start making new friends. There are almost 600 people here this year, and you realize that you won’t succeed, that the weekend will roll around quickly, and you’ll be tweeting people from the airport, apologizing for not finding the time to meet up.

But that is for later. For now, get to know the people in your class, make new friends, create new connections.

The twitter stream is going fast and furious, with the people from all 28 different courses describing the exciting things they will be learning and doing over the next five days. You wish you could be in all the places, learning all the things.

Let that go. There are other years, other opportunities, and enjoy the course you are in, all the things you will learn and do. Saved the shared resources for later. Remember the names of people taking the courses, so you can come back to them later to learn from them.

Don’t feel like you have to do everything, be everywhere, meet all the people, learn all the things, even though you might want to or thing you have to. Take the time you need to unwind, decompress, reflect, rest. Use this space, these blog posts to share, work-through, and geek out.

I’m working through issues around digital pedagogy, rethinking, relearning, reimagining. This is hard work already, being surrounded by dedicated pedagogues and really smart scholars from a wide variety of disciplines, getting comfortable around each other, getting ready to really work hard.

Lunch is looming, stomachs are rumbling, plans are being made. The rush continues. #DHSI2014 is marching on.

May 23, 2014

Four Web Finds for Digital Humanists

Instead of sharing four separate Facebook or Twitter posts, I thought I would collect some recent discoveries of materials that might be of interest to the EMiC community and put them into one blog post. So here is my Friday sampler:

I will be writing more soon on the audio edition of Sepass Poems as I continue to correspond with Ann Mohs of Longhouse Publishing prior to the official launch. For now, check out the audio glossary that has been created to accompany the audio edition. It is a great reminder that paratext (or in this case perhaps a term like paranarrative would be more appropriate) should reflect the medium of the principal text or narrative. It seems fitting that the glossary for orally presented poems is an oral glossary, returning to the tradition of learning new terminology through listening and repetition.

Here is the link to the glossary: http://www.longhousepublishing.com/book-Sepass-Poems-Glossary.htm

For those collecting audio and video in its original form (i.e. magnetic media: floppy discs, cassette tapes, etc.), the Canadian Conservation Institute (CCI) has published S. Michalski’s “Incorrect Temperature” chart as a guide to how long different objects will last at different temperatures based on their vulnerability. The highest sensitivity group includes magnetic media and colour photographs, and various other types of paper (for those of us with large book collections) can be found under the other sensitivity groups. Technically I didn’t discover this online, but the workshop organizer who passed it on during a museum workshop took it from the CCI website. If you’re curious to know how long that copy of bpNichol’s First Screening is going to last in your basement, or what kind of decay rate your collection of rare chapbooks and Modernist periodicals have, this document is worth a glance. If nothing else, it is a reminder of why digitization is necessary for preserving literary works that have a finite lifespan in their original physical form.

For anyone in Halifax who is working on an edition and wants to tackle some basic graphic design work on their own, check out this Intro to Photoshop course offered by Ladies Learning Code (the organization is targeted at women, but men can take the courses, too). I have taken two Ladies Learning Code courses in the past (one for HTML and CSS, and one for JavaScript) and they were both very informative, hands-on, and well-taught. Plus they are very affordable! A Canada-wide organization, Ladies Learning Code offers workshops in many different cities, so sign up for their email newsletter if you want to know of relevant coding, Adobe, and Microsoft Office courses that are coming your way.

This last find is not as directly related to Modernism or editing, but it has filled my head with possibilities. Poet Adrian Sobol has created a digital chapbook by self-publishing poems on Instagram under the account “Selfies with the Moon.” Check it out here.

After thinking about digital strategies for engaging an audience with tools like social media, I am in love with Sobol’s idea! #crowdsourcing #instaeditions #hashtagannotations ? #bpNicholOnInstagram ?? It certainly is something to think about.

May 13, 2014

EMiC 2014-15 PhD Stipend Recipients

The Editing Modernism in Canada Project has awarded the following students PhD Stipends for 2014-2015. Congratulations to this year’s winners!

1) Michael Nardone

Concordia University

Project Title: PHONOTEXT.CA

Phonotext.ca is a project initiated for the creation of a comprehensive open-access digital index of sound recordings related to modernist and postmodernist Canadian poets and poetry. The site will index recordings in all available formats, document any relevant bibliographic information, list where recordings are physically located, and provide links to access recordings that have been made digitally available.

In addition to providing a platform for listening to Canadian poets and poetry, phonotext.ca will serve as an important tool for preserving and accessing phonotextual materials, acting as a hub to catalyze future research and critical study. Funds from Editing Modernism in Canada support developing the site’s indexing and metadata protocols, the initial compiling of resources, and outreach to acquire additional resources among communities of poets, scholars, researchers, librarians and archivists.

2) Carl Watts

Queen’s University

Project Title: Laura Goodman Salverson’s The Dove

In addition to works of autobiography and realist fiction, Laura Goodman Salverson published a little-known novel called The Dove (Ryerson Press, 1933), in which a group of Icelanders is kidnapped by corsairs and sold as slaves in Algiers. While much has been written of the arrangement of realism and romance that informs Canada’s modernist literature, The Dove is unique in that its peculiar historical romance registers a radical inversion of commonly expressed relationships between Europeans and non-Western peoples. It is for this reason that I am proposing a digital edition of the long-out-of-print novel. Based on the first edition as well as the novel’s typescript at Library and Archives Canada, this edition will also include an introduction and notes that draw from archival materials and critical work on Salverson’s corpus.

3) Graham Jensen

Dalhousie University

Project Title: The Canadian Modernist Magazines Project

The Canadian Modernist Magazines Project (CMMP) will focus its attention on the digitization and transcription of a limited selection of Canadian “little magazines” so that their constituent poems, essays, and editorials can be read, searched, and analyzed by scholars within EMiC’s Modernist Commons or using a variety of existing third-party digital humanities tools. Following the precedent set by similar projects—such as the Modernist Journals Project (U.S.A.) and the Modernist Magazines Project (U.K.)—the CMMP will attempt to digitize complete runs of two important Canadian magazines of the 1940s: Preview (1942-44) and First Statement (1942-45). Once these initial goals have been met, the CMMP will have established the online infrastructure and editorial processes necessary for the digitization and transcription of additional magazines. Following the initial funding period, Graham hopes to expand the CMMP through other grants or as part of a postdoctoral research position.

4) Alix Shield

Simon Fraser University

Project Title: Curating Digital Aboriginal Orature and Literature

This project will focus on the digitization, editing, and critical analysis of First Nations orature and literature, looking specifically at the collaboration between Chief Joe Capilano (Sahp-luk) and E. Pauline Johnson (Tekahionwake) that culminated in the text Legends of Vancouver (1911). The project will begin with the gathering of versions of the Legends text, and will then move to the digitization stage, where scans of the various editions will be ingested to EMiC’s Modernist Commons repository and web-based versioning platforms will be used to collate variant texts and produce visualizations that highlight exact instances of change across versions. Finally, the project aims to produce a digital scholarly edition of this collaboratively-authored text, and in doing so engage in the process of repatriation by creating an archival space that involves members of the Coast Salish and Mohawk communities and respects cultural codes and protocols.

May 12, 2014

TEMiC in Review: Transitions and Inspirations

Continuing with posts featuring feedback from TEMiC, Katrina Anderson— an MA student at Simon Fraser University– writes about why she recommends the training event to other humanities students:

Looking back on my experiences at last year’s Textual Editing and Modernism in Canada (TEMiC) summer institute, I have realized what an excellent training opportunity it was for someone just about to begin her first year as an MA student. In many ways, the coursework, seminar discussions, and afternoon workshops prepared me for the transition from undergraduate to graduate studies. The assigned readings that corresponded with the theme “Editing Modernism On and Off the Page” anticipated many of the readings that I would encounter in my first graduate seminars. These seminars, which focused on Print Culture and Digital Romanticism, integrated many of the same issues that were raised during the week at TEMiC. Having already discussed digital and textual editing practices with students and scholars in the EMiC community, I was able to speak and write about them with confidence in my graduate coursework. It was especially helpful to have been introduced to the work of John Bryant, whose fluid-text approach now somehow seems to make its way into every essay that I write.

Aside from providing a solid background in readings on textual and digital editorial theory, the summer institute also helped me to find my current research project. I am hoping to develop an edition of the short stories of Katherine Hale, and my experiences at TEMiC are largely responsible for the conceptualization of this project. My interest in Hale as an author comes out of the research that I did in preparation for the summer institute, and without the knowledge that I acquired at TEMiC (as well as the introduction to digitization methods I received at Digital Editing and Modernism in Canada [DEMiC] /DHSI in Victoria earlier in the summer) I would not have considered a digital edition as something that someone with a humanities background and limited technical skills would be able to develop. I know the almost daunting amount of work that goes into such a project, however what I learned at TEMiC and DEMiC. DEMiC/DHSI gave me the vocabulary and framework I needed to see this as a task someone with my level of training would be able to pursue.

For me, some of the most memorable moments from TEMiC 2013 came out of the afternoon workshops and guest speaker sessions. Getting hands-on experience with printmaking techniques such as screen and letterpress printing was a particular favourite. Listening to scholars speak about their current research was fascinating, and provided a perspective on the diverse array of work being done in digital humanities scholarship. And, of course, being in the audience as Frank Davey, Fred Wah, Sharon Thesen, Daphne Marlatt, and George Bowering read and discussed their works was a real treat.

I feel lucky to have been able to participate in this poetic and editorial event. I am especially grateful to the EMiC community, in particular to Karis Shearer and Dean Irvine, for organizing this training opportunity, and for providing a memorable send-off from my hometown as I made the move to pursue my MA degree.

May 5, 2014

On Using Tools and Asking Questions

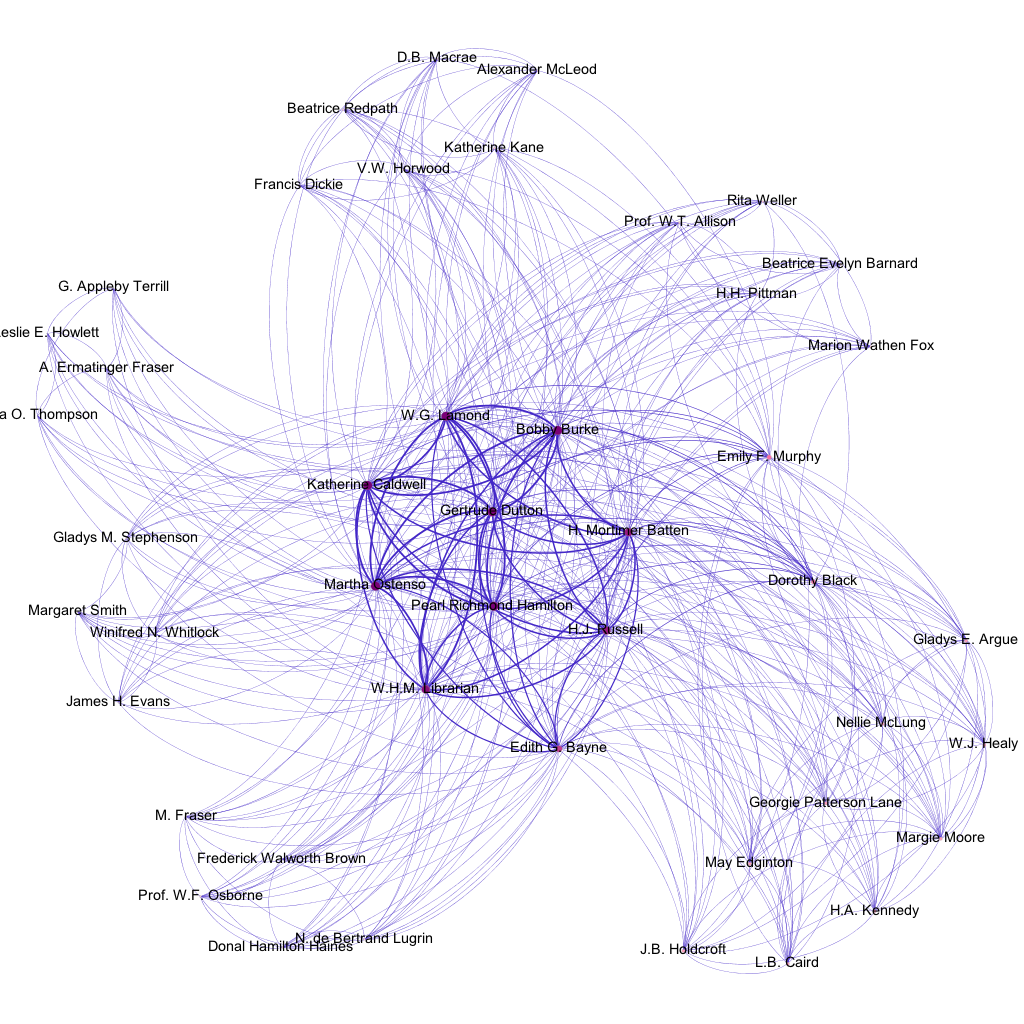

I recently met up with fellow EMiC fellow Nick van Orden, along with a few other colleagues here at the University of Alberta, to discuss our shared experiments in Gephi, “an open graph viz platform” that generates quick and lovely network visualizations. Our meeting was in turn prompted by an earlier off-the-cuff conversation about the pleasures and challenges of exploring new tools, particularly for emerging scholars for whom work that cannot be translated into a line on the CV can often feel like a waste of time. We agreed that spending some time together puzzling over a tool of mutual interest might reduce the time investment and increase the fun factor.

During this first meeting the conversation somewhat inevitably turned to the question of why — why, when there is such a substantial learning curve involved, when it takes SO LONG to format your data, why bother add all? What does a new tool tell me about my object of study that I did not already know, or could not have deduced with old-fashioned analogue methods?

I offer here an excerpt from Nick’s reflection on this conversation, because it is perfect:

DH tools don’t provide answers but do provide different ways of asking questions of the material under examination. I think that we get easily frustrated with the lack of “results” from many of these programs because so much effort goes into preparing the data and getting them to work that we expect an immediate payoff. But, really, the hard intellectual work of thinking up the most useful questions to ask starts once we’re familiar with the program.

The frustration with lack of results, like the frustration with spending time learning something you won’t necessarily be able to use, is based on an instrumentalist approach to academic work that suggests two related things. First, it is, I think, a symptom of the state of the academy in general and humanities in particular. Second, it implies that DH tools should function like other digital tools, intuitively and transparently. I say these points are related because often the instrumentalist approach to scholarship develops into an instrumentalist approach to DH as itself a means for emerging scholars to do exactly the kind of CV-padding that learning a new tool isn’t. And therein lies the value of this “hard intellectual work.”

To illustrate, here is an image of one visualization I produced from Gephi.

This image shows the authors featured in each of the six issues of the magazine Western Home Monthly in which Martha Ostenso’s Wild Geese was serialized between August 1925 and January 1926. It reveals a few things: that there a number of regular feature-writers alongside the shifting cast of fiction and article contributors; that, in terms of authors, different issues thus interweave both sameness and difference; that Ostenso herself briefly constitutes one of those recurring features that characterizes the seriality of the magazine, even if a larger chronological viewpoint would emphasize the difference of these six issues from any others. None of these points are surprising to me; none of them were even, properly speaking, revealed by Gephi. They were, in fact, programmed by me when I generated a GDF file consisting of all the nodes and edges I wanted my network to show.

This image does a much better job of arguing than it does of revealing, because it is based on the implicit argument I formulated in the process of building said GDF file: that a magazine can be understood as a network constituted by various individual items (in this case, authors) that themselves overlap in relationships of repetition and difference. It can thus, as Nick implies, be understood as the result of a series of questions: can a magazine be understood as a network? If so, a network of what? What kinds of relationships interest me? What data is worth recording? What alternate formulations can I imagine, as I better understand what Gephi is capable of?

Work like this is slow, exploratory, and its greatest reward is process rather than product. It may eventually lead to something, like a presentation or a paper, that can show up on a CV, but that is not its purpose. The greatest value of the painstaking work of learning a new tool is this very slowness and resistance to the instrumentalist logics of DH in particular and academic work in general.

What is your experience with learning new tools. What tools have you experimented with? How have you dealt with your frustrations or understood your successes? Do you think of tools as answering questions or helping you to pose better questions? Or as something else entirely?