Archives

Archive for the ‘Technology’ Category

May 5, 2014

On Using Tools and Asking Questions

I recently met up with fellow EMiC fellow Nick van Orden, along with a few other colleagues here at the University of Alberta, to discuss our shared experiments in Gephi, “an open graph viz platform” that generates quick and lovely network visualizations. Our meeting was in turn prompted by an earlier off-the-cuff conversation about the pleasures and challenges of exploring new tools, particularly for emerging scholars for whom work that cannot be translated into a line on the CV can often feel like a waste of time. We agreed that spending some time together puzzling over a tool of mutual interest might reduce the time investment and increase the fun factor.

During this first meeting the conversation somewhat inevitably turned to the question of why — why, when there is such a substantial learning curve involved, when it takes SO LONG to format your data, why bother add all? What does a new tool tell me about my object of study that I did not already know, or could not have deduced with old-fashioned analogue methods?

I offer here an excerpt from Nick’s reflection on this conversation, because it is perfect:

DH tools don’t provide answers but do provide different ways of asking questions of the material under examination. I think that we get easily frustrated with the lack of “results” from many of these programs because so much effort goes into preparing the data and getting them to work that we expect an immediate payoff. But, really, the hard intellectual work of thinking up the most useful questions to ask starts once we’re familiar with the program.

The frustration with lack of results, like the frustration with spending time learning something you won’t necessarily be able to use, is based on an instrumentalist approach to academic work that suggests two related things. First, it is, I think, a symptom of the state of the academy in general and humanities in particular. Second, it implies that DH tools should function like other digital tools, intuitively and transparently. I say these points are related because often the instrumentalist approach to scholarship develops into an instrumentalist approach to DH as itself a means for emerging scholars to do exactly the kind of CV-padding that learning a new tool isn’t. And therein lies the value of this “hard intellectual work.”

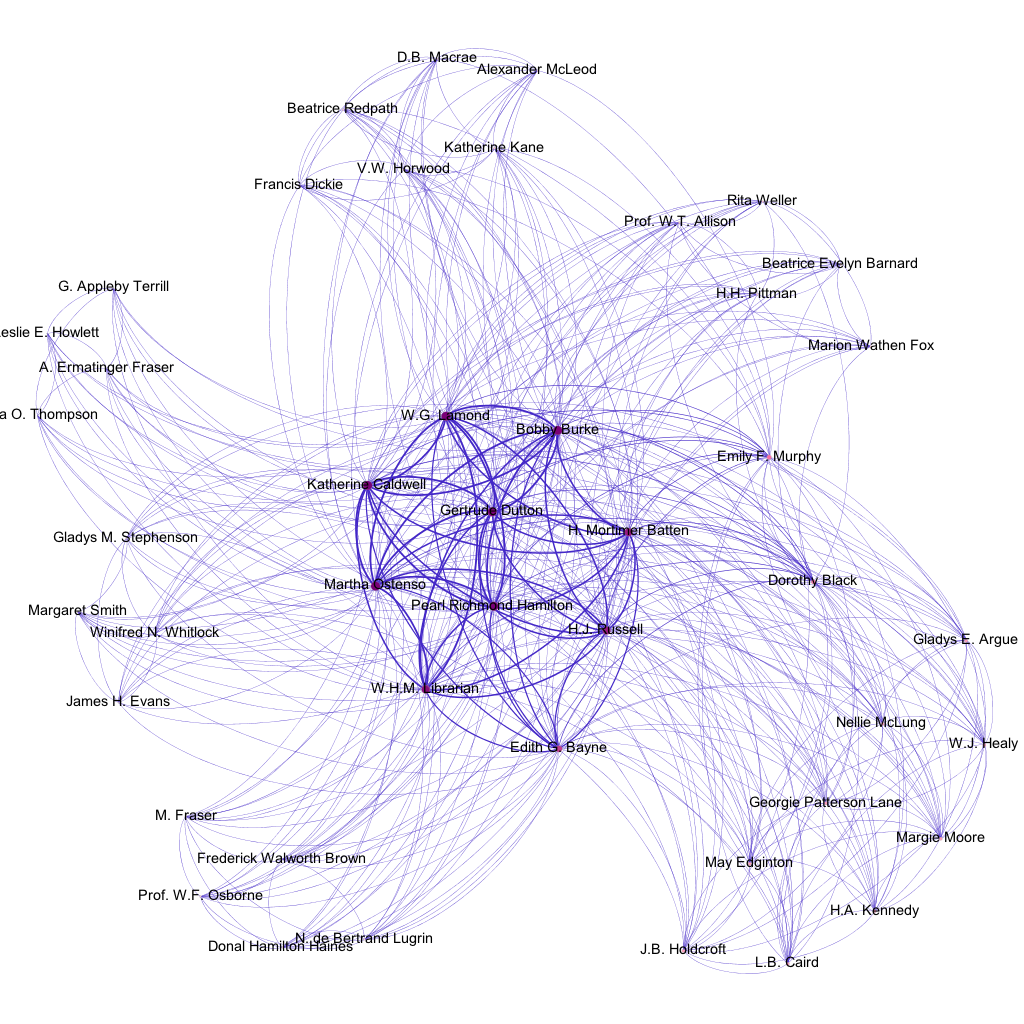

To illustrate, here is an image of one visualization I produced from Gephi.

This image shows the authors featured in each of the six issues of the magazine Western Home Monthly in which Martha Ostenso’s Wild Geese was serialized between August 1925 and January 1926. It reveals a few things: that there a number of regular feature-writers alongside the shifting cast of fiction and article contributors; that, in terms of authors, different issues thus interweave both sameness and difference; that Ostenso herself briefly constitutes one of those recurring features that characterizes the seriality of the magazine, even if a larger chronological viewpoint would emphasize the difference of these six issues from any others. None of these points are surprising to me; none of them were even, properly speaking, revealed by Gephi. They were, in fact, programmed by me when I generated a GDF file consisting of all the nodes and edges I wanted my network to show.

This image does a much better job of arguing than it does of revealing, because it is based on the implicit argument I formulated in the process of building said GDF file: that a magazine can be understood as a network constituted by various individual items (in this case, authors) that themselves overlap in relationships of repetition and difference. It can thus, as Nick implies, be understood as the result of a series of questions: can a magazine be understood as a network? If so, a network of what? What kinds of relationships interest me? What data is worth recording? What alternate formulations can I imagine, as I better understand what Gephi is capable of?

Work like this is slow, exploratory, and its greatest reward is process rather than product. It may eventually lead to something, like a presentation or a paper, that can show up on a CV, but that is not its purpose. The greatest value of the painstaking work of learning a new tool is this very slowness and resistance to the instrumentalist logics of DH in particular and academic work in general.

What is your experience with learning new tools. What tools have you experimented with? How have you dealt with your frustrations or understood your successes? Do you think of tools as answering questions or helping you to pose better questions? Or as something else entirely?

April 22, 2014

Digital Editions @ DHSI@Congress

For anyone who would like to register for the Digital Editions workshop on Friday, May 30th, please see the registration details below. This afternoon workshop will feature the latest iteration of the Modernist Commons. If you can’t make it to DHSI in Victoria, come to Congress at Brock for a preview of EMiC’s digital repository and editorial workbench. Those of you who have seen earlier versions of the Modernist Commons will be interested to see the strides we’ve taken from prototype to production platform over the past few years, and those who are new to EMiC and its infrastructure development can learn how to take advantage of the freely available content-management, optical character recognition, TEI and RDF markup, versioning, collation, and visualization features that the new platform has to offer. If you can make it to DHSI, the Modernist Commons will be demoed for anyone who wants to drop in on Susan Brown’s CWRCshop course.

__________________________

DHSI@Congress 2014 (28-30 May 2014)

The DHSI@Congress is a series of 2.5 hour workshops for scholars, staff, and students interested in a hands-on introduction to the ways that traditional and digital methods of teaching, research, dissemination, creation, and preservation intersect and enhance one another. The workshops are built on the community model of the Digital Humanities Summer Institute at the University of Victoria, which connects Arts, Humanities, Library, and Archives practices and knowledge in a digital context. The workshops are modular and may be taken individually or as a self-directed course of investigation. We invite you to register through the Congress2014 website for any and all workshops that engage your interest.

DHSI@Congress is brought to you by the DHSI in partnership with CSDH/SCHN and the Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences. DHSI@Congress participants must be registered for Congress in order to take part in the workshops. The plenary is free and open to those not registered for Congress.

For more information, feel free to contact the DHSI@Congress organizer, Constance Crompton, at constance.crompton@ubc.ca or follow us @DHInsitute on Twitter.

To register, please visit the Congress registration page (https://www.regonline.ca/Register/Checkin.aspx?EventID=1526736).

June 24, 2013

Hacking and Engineering: Notes from DHSI

A few weeks ago, at DHSI, I was giving a demo of a prototype I had built and talking to a class on versioning about TEI, standoff markup and the place of building in scholarship. Someone in the audience said I seemed to exhibit a kind of hacker ethos and asked what I thought about that idea. My on-the-spot answer dealt with standards and the solidity of TEI, but I thought I might use this space to take another approach to that question.

The “more hack less yack” line that runs through digital humanities discussions seems to often stand in for the perceived division between practice and theory, with those scholars who would have more of the latter arguing that DH doesn’t do cultural (among other forms of) criticism. That’s certainly a worthwhile discussion, but what of the division, among those who are making, between those who hack and those who do something else?

I take hacker to connote a kind of flexibility, especially in regards to tools and methods, coupled with a self-reliance that rejects larger, and potentially more stable, organizations. Zines. The command line. Looking over someone’s shoulder to steal a PIN. Knowing a hundred little tricks that can be put together in different ways. There’s also this little graphic that’s been going around recently (and a version that’s a bit more fun) that puts hacking skills in the context of subject expertise and stats knowledge. Here, what’s largely being talked about is the ability to munge some data together into the proper format or to maybe run a few lines of Python.

This kind of making might be contrasted with engineering—Claude Lévi-Strauss has already drawn the distinction between the bricoleur and the engineer, and I think it might roughly hold for the hacker as well. In short, the bricoleur works with what she has at hand, puts materials (and methods?) together in new ways. The engineer sees all (or more) possibilities and can work toward a more optimal solution.

Both the bricoleur and the engineer are present in digital humanities work. The pedagogical benefits of having to work with imperfect materials are cited, and many projects do tend to have the improvised quality of the bricoleur—or the hacker described above. But many other projects optimize. Standards like the TEI, I would argue, survey what is possible and then attempt to create an optimal solution. Similarly, applications and systems, once they reach a certain size, drive developers to ask not what do I know that might solve this problem but what exists that I could learn in order to best solve this problem.

My point here has little to do with either of these modes of building. It’s just that the term “hack” seems to get simplified sometimes in a way that might hide useful distinctions. Digital humanists do a lot of different things when they build, and the rhetorical pressure on building to this point seems to have perhaps shifted attention away from those differences. For scholars interested in the epistemological and pedagogical aspects of practice, I think these differences might be productive sites for future work.

June 13, 2013

Reflections on DHSI 2013: Or How I Learned to Love Databases and Acronyms (“RoDHSIoHILLDA”)

Ramping up in the wake of Congress, this year’s Digital Humanities Summer Institute, or “DHSI” for the acronym-inclined, gathered an unprecedented number of scholars, students, and researchers for training in, you guessed it, the digital humanities. Thanks to support from the Editing Modernism in Canada project (“EMiC”), a course on Digital Humanities Databases was my home for the intensive five-day summer institute that punctuates class time with colloquium and unconference sessions.

Taught by Harvey Quamen, Jon Bath, and John Yobb, the Digital Databases class led us through project planning, MySQL coding (Structured Query Language), database building, and finally, database queries that enable you to ask specific research questions. In short, I mapped out and built a database on Canadian literary adaptations in five days (however minimally populated it may be). When organizing the structure of my database and its multiple tables, I found it very helpful to think of the connected tables as a sentence: there is usually a subject (e.g. person), verb (e.g. adapting), and object (e.g. source). As with literary work, I learned that too much repetition is a bad sign and that spelling counts; the latter was quite horrifying for someone like me who is codependent on autocorrect because there is no autocorrect or red underline to aid in spelling or typos. I also made sure to take advantage of the one-on-one help from Harvey and the Jo(h)ns.

Andrea Hasenbank—an EMiC Doctoral Fellow—introduced the class to a free, online website called “SQL Designer” that not only enabled me to map out nine inter-related tables but also created the MySQL commands. Although seemingly sent from the digital gods, it still requires a background in MySQL in order to understand how to use, navigate, and implement the Designer, but the first three days of the Digital Databases course covers many of the database-specific commands and related structures. For those interested in taking the course and/or trying out SQL Designer, I have a few tips from a novice’s perspective:

– Be sure to save the database design often; I saved mine in my browser under a unique name.

– There is a button that will create foreign keys for you (which link two tables together). At first, I typed in all the foreign keys myself before discovering that the Designer will create and appropriately name foreign keys in junction tables. (For those unfamiliar with databases yet, fret not, this jargon will be all too clear by the end of the course’s first day.)

– There were some glitches for me in the MySQL Code, such as the repetition of the “null” command and the addition of “primary key” commands in junction tables that included no primary keys. Also, be sure to erase the last comma in a list of commands before the closing bracket and/or semicolon.

– I needed to edit the generated MySQL commands in a text editor (such as Text Wrangler) before inputting it into Terminal.

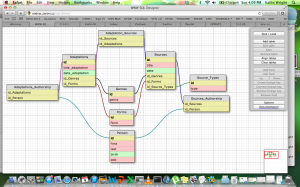

Here is a sample draft of my database design in SQL Designer:

You will notice that the SQL Designer can also encode the column type (primary id, date, foreign key, etc.).

My research investigates how Canadian literature rewrites popular narratives—Greek myth, Shakespearean plays, colonial legend, national histories—by changing the identities of marginalized characters. I examine Canadian revisionist plays that critique cultural figures like Philomela, Othello, and Pocahontas as reductive emblems of layered racial, sexual, and gendered identities. The digital Canadian Adaptations of Shakespeare Project, or if you haven’t had enough exciting acronyms, “CASP,” features an online database that has been integral to my research (Daniel Fischlin). Building on CASP, I am interested in creating a database that encompasses multiple sources and enables researchers or students to search Canadian adaptations of Greek mythology, the Bible, and Native mythology, to name a few. You could also, for instance, limit your search by author, date, and/or location that would list all the Canadian adaptations of Ovid, during post-WWI Canada, and/or in Nova Scotia. This database would help establish a wider field of Canadian adaptation studies.

The Digital Humanities Databases course cemented my appreciation of digital tools for literary scholarship . . . as well as my reliance on acronyms. Last but not least, thanks to the Databases course, I now understand why this is funny:

June 20, 2012

Editing Modernism in Canada joins DHWI!

[Cross-posted from http://www.mith.umd.edu/dhwi/]

The Editing Modernism in Canada (EMiC) project and the Digital Humanities Winter Institute (DHWI) are delighted to announce the 8th course for the upcoming 2013 institute. Digital Editions, led by EMiC director Dean Irvine, is designed for individuals and groups who are interested in creating scholarly digital editions. Topics covered will include an overview of planning and project management, workflow and labour issues, and tools available for edition production. Participants will be working with the Modernist Commons, a collaborative digital editing environment and repository designed by EMiC in collaboration with Islandora and its software-services company DiscoveryGarden.This course was made possible through the generous sponsorship of EMiC. We invite you to visit DHWI and EMiC to learn more about this training opportunity and this exciting international project.

EMiC participants (faculty, postdocs, graduate and undergraduate fellows) and other students affiliated with EMiC co-applicants and collaborators may apply to attend DHWI online at http://editingmodernism.ca/training/summer-institutes/demic/.

Read the new DEMiC, DEMiC Travel, and DEMiC Accommodations pages and Application Form carefully. There are new deadlines and new mechanisms of oversight for booking travel and accommodations for both DHSI at Victoria and DHWI at Maryland.

Looks like we’re going to have to update that summery URL. Welcome to winter training. Now there’s no off season for DH enthusiasts.

June 13, 2012

Radical, Humane & Digital

The editors of Book 2.0 invite articles on the rapidly growing application of digital tools to research and publishing strategies in the humanities and social sciences for a special issue scheduled for 2013.

Contributions may relate to curating online collections and archives, the design and implementation of new applications that support or enrich research, and emerging forms of cross-disciplinary scholarship that are supported by technology. In particular, we welcome submissions on innovative publishing and dissemination models that increase access to digitised and born-digital materials. Abstracts of no more than 200 words should be submitted to Dr Mark Turin <mark.turin@yale.edu> and Dr Mick Gowar by 4 August 2012.

Book 2.0 is a new, interdisciplinary peer-reviewed journal focusing on developments in book creation and design—including the latest in technology and software affecting illustration and production. Book 2.0 also explores innovations in distribution, marketing and sales, and book consumption, and in the research, analysis and conservation of book-related professional practices. Through research articles and reviews, Book 2.0 provides a forum for promoting the progressive practice in the teaching of writing, illustration, book design and publishing across all sectors.

To read Issue 1, Volume 1 of Book 2.0 for free, please visit http://bit.ly/Book201 Or read our blog at http://booktwopointzero.blogspot.co.uk

June 9, 2012

DH Tools and Proletarian Texts

(This post originally appeared on the Proletarian Literature and Arts blog.)

I’m at the Digital Humanities Summer Institute at the University of Victoria this week. I’m taking a course on the Pre-Digital Book, which is already generating lots of interesting ideas about how we think and work with material texts, and how that is changing as we move into screen-based lives. There are, of course, many implications for how these differing textual modes relate to how we study and teach proletarian material, and more importantly, how class bears on these relationships. I hope to share some of these ideas as they have developed for me over the week. The course has taken up these questions in relation to medieval manuscripts and early modern incunablua and print, but the issues at stake are relevant for modern material as well. The instructors and librarians were kind enough to bring in a 1929 “novel in woodcuts” by Lynd Ward for me to look at – more on that will follow.

But, for fun, I also wanted to post about a little analysis experiment I did with some textual analysis tools.

I used the Voyant analysis tool to examine a set of Canadian manifesto writing. I transcribed six texts either from previous print publications or from archival scans for use as the corpus. These included: (1) “Manifesto of the Communist Parties of the British Empire”; (2) Tim Buck, “Indictment of Capitalism”; (3) CCF, “Regina Manifesto”; (4) Florence Custance, “Women and the New Age”; (5) “Our Credentials” from the first issue of Masses; and (6) Relief Camp Workers Strike Committee, “Official Statement”. [The RCWSC document remains my favorite text of all time.] Once applied, the tools let me read the texts in new ways, pulling out information or confirming ideas that I had about them in meaningful ways. You can find the summary of my corpus here.

The simplest visualization is the Cirrus word cloud, which at a glance shows that these texts are absolutely dominated by the language of class and politics (unsurprising, as they are aimed at remaking the existing class order). Michael Denning’s statement in The Cultural Front that the language of the 1930s became “labored” in both the public and metaphoric spheres is clearly reflected in this image.

Cirrus visualization of Canadian manifesto texts

Cirrus visualization of Canadian manifesto texts

Looking at the differences among the materials, an analysis of distinctive words is a simple way to get at the position of a given text in relation to the others. We might think of these Canadian manifestos as occupying the same ground of debate (though they are not responding to one another directly), but not necessarily sharing the same tent. For example, the “Manifesto of the Communist Parties of the British Empire” shows a much higher concentration of the term “war”, which helps situate it to later in the 1930s. The “Regina Manifesto” is overwhelmingly concerned with the “public” as it plans for a collective society. Florence Custance’s feminist statement shows itself to be more unique in its own time, as it uses “women” and female pronouns far beyond the other texts. And the Masses text betrays its literary periodical background with its heavier use of “art”.

The density of vocabulary in the texts can tell us something about intended readerships, and purpose of the text. Masses plays with the linguistic conventions of the manifesto to develop a text that is both assertive and creative; accordingly, it uses the largest variety of words to do so. However, the RCWSC is not far behind in its forthright call to action, which tells me something interesting about the role of the imaginative mode in connecting revolution with creative acts. Buck’s “Indictment” is the least dense text. It’s also the longest, which makes for a highly repetitive text. The “Indictment” has a strong oral quality to it, commenting on Buck’s trial and defense and with response and Marxist analysis. It is also highly indebted to that style, parsing its terms minutely and using them for step-by-step explanations. It is in many ways the most didactic of the texts, as the word density suggests, though such analysis misses the purposeful element of the limited word choices. I find Buck’s repetition to have an incantatory quality connecting it more closely to spoken debate than the other texts, an impression that comes out of working with the text closely, while typing and re-typing, and reading it aloud for myself. Word density is not for me an assignation of value; rather, it is one of many ways of framing some thoughts on how these texts – and manifestos more broadly – employ particular rhetorical modes and how we can follow them through.

Here is the link to the Voyant analysis of my manifestos. I invite you to take a look, play around, and consider throwing up some text from other working-class and proletarian sources. It seems to me that a lot of textual analysis begins by reaching for “important” texts – those that are canonical, or historical. The tools make no distinction – I would like to see more examples of writing from below feeding into the ways we think about texts in the DH realm.

October 18, 2011

Is Creating Community a Primary Function of the Digital Humanities?

In my “Digital Romanticism” class with Michelle Levy at SFU, we recently hosted Professor Andrew Stauffer, Director of the NINES project at the University of Virginia. The resulting conversation touched on some core questions about the purpose of the digital humanities, and its future potential, particularly as it pertains to the question of scholarly communities. I think EMIC scholars will find there are interesting points of reference here for our own community-building efforts.

In preparation for the class, we read John Unsworth’s article “Scholarly Primitives: what methods do humanities researchers have in common, and how might our tools reflect this?” In this article (taken from a presentation he gave at a symposium in London) he gives a list of scholarly “primitives” – “basic functions common to scholarly activity across disciplines, over time, and independent of theoretical orientation.” These are: discovering; annotating; comparing; referring; sampling; illustrating; and representing.

Unsworth is clear that he doesn’t think this list is exhaustive, and I wonder if he (or you) would think that “creating community” should qualify as a primitive. Scholars have been incredibly good at creating communities (if you agree, contra i.e. Wendell Berry, that a community doesn’t need to inhabit one geographic location). The conversation that happens in these communities across space and time is crucial to scholarly work.

What excites me about NINES is that the community-oriented features of other non-scholarly online spaces are built into it in in a unique way. I haven’t seen other scholarly sites foreground tagging and discussing, with activities attached to personalizable profiles, in the same way NINES and 18thConnect have.

Sadly, these features are under-used. Talking with Professor Stauffer, I can see the clear need for NINES to use its limited resources on improving the more standard database functions that are the primary reason scholars find NINES so useful (improvements include building a tool, Typewright, that will allow scholars to correct OCR scans, for example).

If we agree that creating community is indeed a crucial part of scholarly work, however, then there is ample incentive to persist in community-building online. The added advantage of the web is that it often creates less hierarchical, more transparent communities with a lower barrier to entry than a non-digital community has. The general tendency of DH to reflect the decentralizing and empowering nature of the web within its own projects and communities is part of what, I think, makes it so exciting and potentially transformative.

It would be fantastic to focus on encouraging people to use the community-oriented functions on NINES (especially the tagging, since it has a clear link to democratizing the classification [and therefore control] of knowledge) but, as I said, NINES faces resource constraints and has other tasks it needs to do.

Getting creative, someone from our class had the fantastic suggestion that NINES could mirror the conversations that take place on some of the bigger nineteenth-century listservs. it seems scholars often don’t feel these conversations are the best use of inbox space, but that having a searchable archive of them would be very valuable and perhaps even help these conversations flourish. I also suggested trying to popularize a #nines hashtag on twitter, hopefully creating another conversation that could simply be mirrored on NINES (this would take time and resources to accomplish, however).

It’s not that scholarly conversation isn’t happening on the web – it’s just that it’s often not happening on purpose-built tools like the Nines discussion boards. One major learning in online outreach over the last few years has been to recognize that the phrase “If you build it, they will come” is simply not true. Instead, you need to find ways to meet people where they are, and then integrate conversations happening in different places.

I’m really impressed with the collaborative effort it must have taken just to get all of the NINES federated sites to play nicely with each other (a Star Trek joke just flickered across my mind, but I’ll leave it to your imagination). The EMIC Commons will be another example of a large-scale scholarly collaboration. But the online community-building efforts seem to lag behind. That’s to say nothing of the efforts to bridge academic and non-academic communities. Online scholarly community building will definitely require some very creative approaches, given some of the challenges Professor Stauffer outlined for us.

A quote from Unsworth’s article is relevant here: “The importance of the network in all of this cannot be overstated: with the possible exception of a class of activities we’ll call authoring, the most interesting things that you can do with standalone tools and standalone resources is, I would argue, less interesting and less important than the least interesting thing you can do with networked tools and networked resources. There is a genuine multiplier effect that comes into play when you can do even very stupid things across very large and unpredictable bodies of material, with other people.”

Keeping the potential of the multiplier effect in mind, I’m wondering if people have other thoughts about this question of creating community online. How does the aim of community-building fit into your DH/EMIC work, if at all?

September 14, 2011

Integrated Digital Humanities Environments: A Commonwealth of Modernist Studies

I have been a Postdoctoral Research Fellow with Editing Modernism in Canada for just over a year now, so it gives me great pleasure at this midpoint in my position to announce two major partnership agreements signed last week. First, EMiC has finalized it contract with Islandora at the University of Prince Edward Island to build our very own Digital Humanities module. Second, EMiC has partnered with another DH project with which I am involved: The Modernist Versions Project. Both partnerships promise to provide resources, training, and infrastructure not only EMiC scholars, but to the DH community as a whole.

1. Integrated Digital Humanities Environments: Islandora

Anyone who has been in DH for a while knows that there is a long history of tool-creation for our scholarly endeavours. Some of these projects have been successful (The Versioning Machine, Omeka, etc.), and some, unfortunately, have not. One “problem” we face as DH’ers is that there is simply so much to do. Some of us are interested in visualization software and network relations (Proust Archive), some are interested in preserving disintegrating archives (Modernist Journals Project), and others of us are firmly rooted in TEI and textual markup. Moreover, with the growth of GIS software, mapping texts has become a great way to have students interact with texts in spatial terms and to communicate with a non-academic public using a language most of us are familiar with: maps.

But what happens in DH when we move into the classroom?

I recently read a stunning syllabus created by Brian Croxall at Emory University, in which he provides his students with a solid (and diverse) introduction to the Digital Humanities. But one thing researchers and teachers like Brian, or any other DH’er faces, is providing students integrated learning environments where they can edit texts in a common repository AND have all the tools they need at their disposal in the browser. If you want to teach TEI right now, you have to buy Oxygen (a life-saving program when it comes to XML markup); For versioning, you must install Juxta or The Versioning Machine. For publication/exhibition you must install Omeka. But what if we had ALL of those things in one learning environment, in one common and open system? This is what we’re trying to accomplish with the EMiC Digital Humanities Sprout.

EMiC Digital Humanities Sprout

An issue EMiC faces in providing tools for our researchers is the sheer diversity of work being undertaken right now by EMiC scholars who have varying levels of experience with digital environments. EMiC needed to find a way to allow its members to preserve, edit, and publish digital editions of archival material in an intuitive way; moreover, we wanted to make to sure our archival practices conformed to international standards. Moreover, most of us are teachers too. How do we teach our students what we are doing in our research? Enter Islandora.

Islandora

Nine months ago, I Googled the phrase “TEI, ABBYY, XSLT” on a whim (actually, I was being lazy: I was looking for an XSLT sheet that would transform ABBYY HTML to simple TEI). The first result listed was a page from the University of Prince Edward Island—just down the road so-to-speak. Not knowing much about Prince Edward Island outside of L. M. Montgomery, I keep browsing, and to my amazement, found that the library at UPEI had created a project called “Island Lives,” a resource developed using the home-grown Islandora digital repository. Mark Leggott, Donald Moses, and others, had built precisely what I was looking for: a digital asset management system using a Fedora Commons repository wrapped in Drupal shell. Islandora allows users to easily upload an image of text to its database, edit that image (TEI), and then “publish” a complete text (book, pamphlet, etc.) to the web. Dean Irvine and I realized that if we could expand this system to fit EMiC’s needs, we could create a Digital Humanities module that would serve our members perfectly. We decided to focus on the core issues facing EMiC editors: Ingestion (including OCR based on Tesseract), Image Markup, TEI editing, Versioning, and Publication (for the full list of what we’re building, see below*). Moreover, Islandora is tested and true and is being used by NASA, the Smithsonian, among many other institutions.

Thank You, DH.

We have years of successful work to emulate for this DH module. And just as the DH community has given to us, we expect the give back to the DH community by keeping the DH module open to use. Yes, we plan on creating an EMiC/Islandora DH install that you can download and use in your classrooms.

If you’re interested in what we’re building, please email Dean Irvine or Matt Huculak with your questions.

As part of this initiative, I have moved to Prince Edward Island to work with the Islandora crew as we develop this module. There’s some other news about what I’ll be digitizing there to “test” our system—but you’ll have to wait to hear about that. In the meantime, we are planning unveiling our functioning module at DHSI2012.

2. Modernist Versions Project

If you haven’t been to the Digital Humanities Summer Institute hosted by Ray Seimens at the University of Victoria, do plan on going! It is an incredible week of DH training, and it is one of the most memorable “unconferences” I have ever attended. One wonderful result of this year’s camp was the creation of the Modernist Versions Project (MVP), an international initiative to provide online resources for the editing and display of multiple witnesses of modernist texts. In what was truly a conversation over coffee, Stephen Ross shared with me his desire to create the MVP. Having served the Modernist Journals Project (MJP) at the University of Tulsa and Brown University for over six years, I said, “Stephen, let’s do this!” And we did. With the help of James Gifford, Jentery Sayers, and Tanya Clement (who along with Stephen and I serve as the Board of the MVP), we have secured tremendous support for a major SSHRC application this fall. The MVP promises to be an important project in the field of Digital Humanities and modernism.

But what does this have to do with EMiC?

I am impressed by two aspects of EMiC. First, the recovery of modernist Canadian texts in our project is truly spectacular. Second, the training EMiC facilitates at the University of Alberta, Dalhousie University, The University of Victoria, and Trent University (among many other institutions) is edifying. Just look at our graduate student editors who are engaged in serious textual editing projects across Canada: http://editingmodernism.ca/about-us/. We are really building the future of Canadian studies here.

As an international scholar, I am concerned, like many of you, with the networking of Canadian modernism across the globe. How does Canadian modernism fit into the greater narrative of modernity across the world? (this is a topic we’ll be exploring in Paris 2012: http://editingmodernism.ca/events/sorbonne-nouvelle/).

The Modernist Versions Project is one way of creating networks of modernist textual criticism and production across the world; that is, the MVP is interested in the editing and visualization of multiple textual witnesses no matter where those witnesses were created. Though located in Canada, the MVP’s scope is much larger, and EMiC’s partnership with the MVP will allow EMiC scholars interested in “versioning” to use MVP resources as they are developed. The MVP has already developed partnerships with the Modernism Lab at Yale University, Modernist Networks at Chicago, and NINES, which is letting us use and develop their Juxta software for periodicals and books.

Dean Irvine has been very generous in allocating my Postdoctoral hours towards the formation of the MVP. Once again, EMiC is nurturing young projects and helping create a truly global network of digital modernist studies. And I think I’ll end on this note: EMiC’s primary focus has been collaboration: collaboration among peers, and now collaboration among projects. And by collaborating with other projects around the world, we hope to create tools that will last, be useful, and really change the face of modernist studies.

Welcome to EMiC. Let’s go build something.

*Details of the EMiC Digital Humanities Sprout

Existing Islandora Code

1. Islandora Core

a. Integration with the Fedora repository and Drupal CMS

b. Islandora Book Workflow

c. Islandora Audio/Video

d. Islandora Scholarly Citations

New/Enhanced Functionality for the EMiC Module

1. Smart Ingest

a. Use open source Tesseract OCR engine

b. Integration of TIKA

2. Image Markup Tool

Proofs of concept and models:

Image Markup Tool (IMT)

Text-Image Linking Environment (TILE)

3. TEI Editor

Proofs of concept and models:

Canadian Writing Research Collaboratory (CWRC) – CWRC Writer

Humanities Research Infrastructure and Tools (HRIT) – Editor

4. Collation Tool

Proofs of concept and models for development:

5. Version Visualization Tool

Proofs of concept and models:

On the Origin of Species: The Preservation of Favoured Traces

6. Dynamic Version Viewer

Models:

Hypercities database: Transparent layers interface

7. Digital Collection Visualization Tool

Proof of concept:

August 14, 2011

Diary of a Digital Edition: Part Five [On Modularity]

Having been an English student for more years that I want to count (but if we’re keeping track, nine—yipes!—years at the university level), it’s sometimes easy to feel like I’ve got the basics of being an academic figured out. Much of the time, the learning I do is building on things I already know or refining techniques that I’ve long been practicing. My thinking often shifts and slides, or becomes more nuanced, but I think it would take a lot to completely transform the way I understand, say, Canadian modernism.

As a DH student, though, those statements absolutely do not apply. Every time I walk into a DH classroom—at DEMiC or at TEMiC, or even just in conversation with other DHers—it’s all I can do to keep up with the ways in which my thinking and practice are continually transforming themselves. The Wilkinson project is a case in point. I started out thinking that I’d be able to do a digital collection of all of her poems—after all, there are only about 150. Then I recognized that facsimiles on their own were inadequate, so the project grew exponentially when I took into account all of the versions—up to 30, for one poem—that I would have to scan, code, and narrativize to create a useful genetic edition. That project was clearly too big to even mentally conceive of right now, so I broke it down into smaller chunks: the 1951 edition first, then the 1955, then the 1968, and so on. Then I broke those chunks down into smaller parts, all the while keeping in view everything I was learning from the EMiC community about DH best practice as I made more and more specific choices about the edition.

As my three weeks in DH studies this summer have made very apparent to me, modularity is now the name of the game (and all credit for this recognition on my part goes to Meagan, Matt, Zailig, and Dean). The idea of modularity is important for my editorial practice, my future as an academic, and my mental health. I always have my ultimate goal—The Collected Works of Anne Wilkinson—in view, but what I used to think of as a small-ish project I now realize will probably take me a decade to completely finish. A more manageable chunk to start with is one module (of probably 10): a digital genetic/social-text edition of Counterpoint to Sleep, Wilkinson’s first collection. Even the first edition, which I’m aiming to have ready for final publication by the time I finish my PhD this time in 2013, can be broken down into smaller modules. First will come the unedited facsimiles. Then, the transcriptions. Then, the marked up facsimiles with their revision narratives and explanatory notes. Each of these modules can be published as soon as they are complete; they don’t represent my final goal for the edition, but they will certainly be useful to readers as I work on the next layer of information.

Modularity makes a lot of sense to me. Counterpoint can be published in the EMiC Commons and go on my CV before I go on the job market, which should help make possible my having the chance to keep working on the Wilkinson project as an academic. By breaking it down, I don’t have to try to mentally wrangle a huge and complex project. And if I hate how Counterpoint turns out, if someone has a really great criticism that I want to act on, if DH best practice changes significantly, or if the EMiC publication engine means that I can do things quite differently, I can completely re-theorize the next edition, The Hangman Ties the Holly, and do quite different things with it. This is especially important when it comes to peer review. If a modernist peer-review body gets created for our digital projects, I want to be able to design my editions so that they will be successfully peer reviewed, and I likely won’t know what those criteria are until after the first edition is done.

The idea of modularity also works quite well for edition and collection design. You’ll note that I’ve given up debating what to call the Wilkinson project, at least for the moment. The individual modules will be called editions, and the modules together will be called collections. I might change my mind later, but rest assured, this will never be called the Anne Wilkinson Arsenal (no offence to Price). I’ve mocked up the splash page for what the Wilkinson collection will look like when the five poetry editions are done.

As you can see, it’s really just a bunch of boxes. And I can have as many, or as few, boxes as I currently have work complete. Those boxes can also become other things as the project gets bigger. In the end, they might say something like Poetry/ Prose/ Life-Writing/ Juvenilia/ Correspondence. They’re endlessly alterable and rearrange-able, which seems to be the core of my new editorial philosophy.

If I can sum up the sea-change that has happened in my thinking about digital editing this year, it’s a shift from thinking big and in terms of product to thinking small and in terms of process. If I didn’t learn anything else, that would be a huge lesson to have grasped. I did learn lots else—the importance of user testing and project design, how committed I am to foregrounding the social nature of texts, how much I love interface design, how much I believe that responsible editing means foregrounding my role as editor and the ways I intervene in Wilkinson’s texts—and I’m looking forward to learning lots more in my hopefully long career as a digital humanist. It’s been a big summer for Melissa as DHer.

There’s a lot I can’t do with the Wilkinson project while Dean, Matt, the PEI Islandora team, and all sorts of other EMiC people work together to get the EMiC Co-op and Commons up and running. It’s just not quite ready for me yet. But there’s a lot I can do: secure permissions for all of the versions of poems that aren’t in the Wilkinson fonds and scan them, create a more refined system to organize all of my files, start writing my editorial preface (very roughly, and mostly so that I don’t forget what I think is most important for readers to know about the edition and my editorial practice), and start narrativizing the revision process of the Wilkinson poems that undergo significant alteration. And (you’ve probably guessed what I’m going to say), I’ll try to make sure that however Islandora turns out, the work I do can be altered and shifted to work with it. It’s going to be a fun fall.