Archives

Author Archive

September 5, 2014

Friday Roundup

It’s been a busy week for everyone with back to school and back to teaching, and a busy week in DH and modernism on the web. Here’s a roundup of events, CFPs, and jobs that the EMiC community might find of interest:

- The College English Association, a gathering of scholar-teachers in English studies, welcomes proposals for presentations for our 46th annual conference, on the theme of IMAGINATIONS. Conference: March 26-28, 2015 | INDIANAPOLIS, INDIANA Submission deadline: 1 November 2014 at http://cea-web.org/ The special panel chair for Digital Humanities (E. Leigh Bonds <leigh.bonds@case.edu>) welcomes proposals for papers and panels addressing the following topics:

- DH projects (digital collections/archives, digital editions, interactive maps, 3D models, etc.)

- DH research tools (text analysis, visualization, GIS mapping, etc.)

- DH pedagogy (teaching methodologies, curriculum development, project collaboration, etc.)

- DH centers (supporting research, consulting services, teaching faculty/students, etc.)

- Digital Project Management

- Data Curation

- The Future of DH

- The Northeast Modern Language Association (NeMLA) is holding its 2015 conference in Toronto, and there are a number of panels of interest to (or organized by members of) the EMiC community. Abstracts are due September 30: https://nemla.org/convention/2015/cfp.html

- Interested in becoming a Digital Humanities Specialist at the University of Alberta? The posting closes September 30. http://careers.ualberta.ca/Competition/S101324477/

- It’s back to school at HASTAC too, and they’ve got lots going on

- Applications for the HASTAC Scholars program are due on September 15: http://www.hastac.org/scholars/apply/form

- Proposals for the 2015 HASTAC conference are due October 15: http://www.hastac2015.org/call-for-proposals/

- The new HASTAC hub at the Graduate Centre at CUNY, The Futures Initiative, is well worth a look: http://www.gc.cuny.edu/Page-Elements/Academics-Research-Centers-Initiatives/Initiatives-and-Committees/The-Futures-Initiative

- Chronicle Vitae has recently launched a series of discussion groups that are already bringing scholars and alternative academics across many fields. You can check out the existing ones here, and there are more to come: https://chroniclevitae.com/groups

- DHSI 2015 is still a ways off, but the new three-week course schedule and course descriptions (including a number of courses designed and taught by the members of the EMiC community) are already online. Scope out the offerings here: http://dhsi.org/courses.php

- The Modernist Studies Association journal Modernism/Modernity has a new Facebook page. Check it out here: https://www.facebook.com/mod.modernity?fref=ts

- If you haven’t yet taken a look at the incredible work being done by the Modernist Magazines Project Canada, you really should: http://modmag.ca/

Happy weekend!

June 9, 2014

Updated: Goodbye, DHSI

DHSI 2014 is done, and most EMiCites will be heading home tonight or early tomorrow. Many have captured their experience of DHSI—some in Victoria for the first time, others for the last—on the EMiC blog. If you were were too busy XSLTing or doing yoga on the lawn of the cluster housing to keep up, now’s your chance: a roundup of DSHI 2014 blog posts is below. The list will be updated as more posts are published.

Lee Skallerup Bessette acknowledges the overwhelm that is DSHI Day One: http://editingmodernism.ca/2014/06/dhsi2014-all-the-things-all-the-people/

Hannah McGregor talks network visualization and the role of DHSI in fostering EMiC and DH community: http://editingmodernism.ca/2014/06/thinking-with-networks/

Chris Doody reports back from Zailig and Josh Pollock’s new course in collaborative XSLT: http://editingmodernism.ca/2014/06/a-collaborative-approach-to-xslt-and-a-riddle/

Emily Ballantyne advocates for the the value of vocabulary, not just expertise: http://editingmodernism.ca/2014/06/the-art-of-conversation-learning-the-language-of-xslt/

James Neufeld reflects on the experience of one again being an apprentice: http://editingmodernism.ca/2014/06/lessons-learned-from-collaborative-xslt/

Marc Fortin creates beautiful visualizations of Aboriginal language networks: http://editingmodernism.ca/2014/06/visualizing-the-landscape-of-aboriginal-languages/

Kaarina Mikalson absorbs confidence from the community of DHSI, of EMiC, and of DH: http://editingmodernism.ca/2014/06/on-belonging/

Emily Ballantyne says goodbye to DHSI after 6 years: http://editingmodernism.ca/2014/06/saying-goodbye/

And so does Jeff Weingarten: http://editingmodernism.ca/2014/06/thoughts-on-the-last-dhsi/

Sarah Vela on her first DHSI, and the learning curve of DH: http://editingmodernism.ca/2014/06/dhsi-and-the-never-ending-learning-curve-of-the-digital-humanities/

Emily Robins Sharpe on the affective side of collaboration: http://editingmodernism.ca/2014/06/what-does-it-mean-to-collaborate/

Alana Fletcher demos out-of-the-box text analysis: http://editingmodernism.ca/2014/06/tool-tutorial-out-of-the-box-text-analysis/

Anouk Lang gives us eleven more reasons (on top of her original twenty-two) to go to DHSI: http://editingmodernism.ca/2014/06/thirty-three-ways-of-looking-at-a-dhsi-week/

April 30, 2014

Looking for Signposts

One of Editing Modernism in Canada’s primary objectives is “to train students and new scholars using experiential-learning pedagogies.” In an academic job market where the digital humanities seem to be opening up a new field into which young scholars can move, but where there still aren’t enough jobs to go around, and in a world when many of us pursue graduate degrees knowing that the professoriate isn’t for us, to what end is EMiC training emergent scholars? Where are we ending up? And how does the training we’re receiving through EMiC help us get there?

No longer the new kid on the block, EMiC has been around long enough to have trained and graduated dozens of students, many of whom are out in the world doing fascinating things that aren’t professorial. There’s Meagan Timney, EMiC’s first postdoc and a senior product designer at the e-reading company Inkling. There’s Katherine Wooler, the Museum and Communications Coordinator for the Nova Scotia Sport Hall of Fame. There’s Gene Kondusky, who is a high school teacher in Manhattan. There’s Reilly Yeo, who is the Managing Director of Open Media and a facilitator with Groundswell Grassroots Economic Alternatives. There’s me, Research Officer in the Faculty of Graduate Studies at York University. And there are all sorts of others. We are current EMiC fellows and EMiC alumni, and we owe our success, in some part big or small, to the skills, training, and mentorship we received through EMiC.

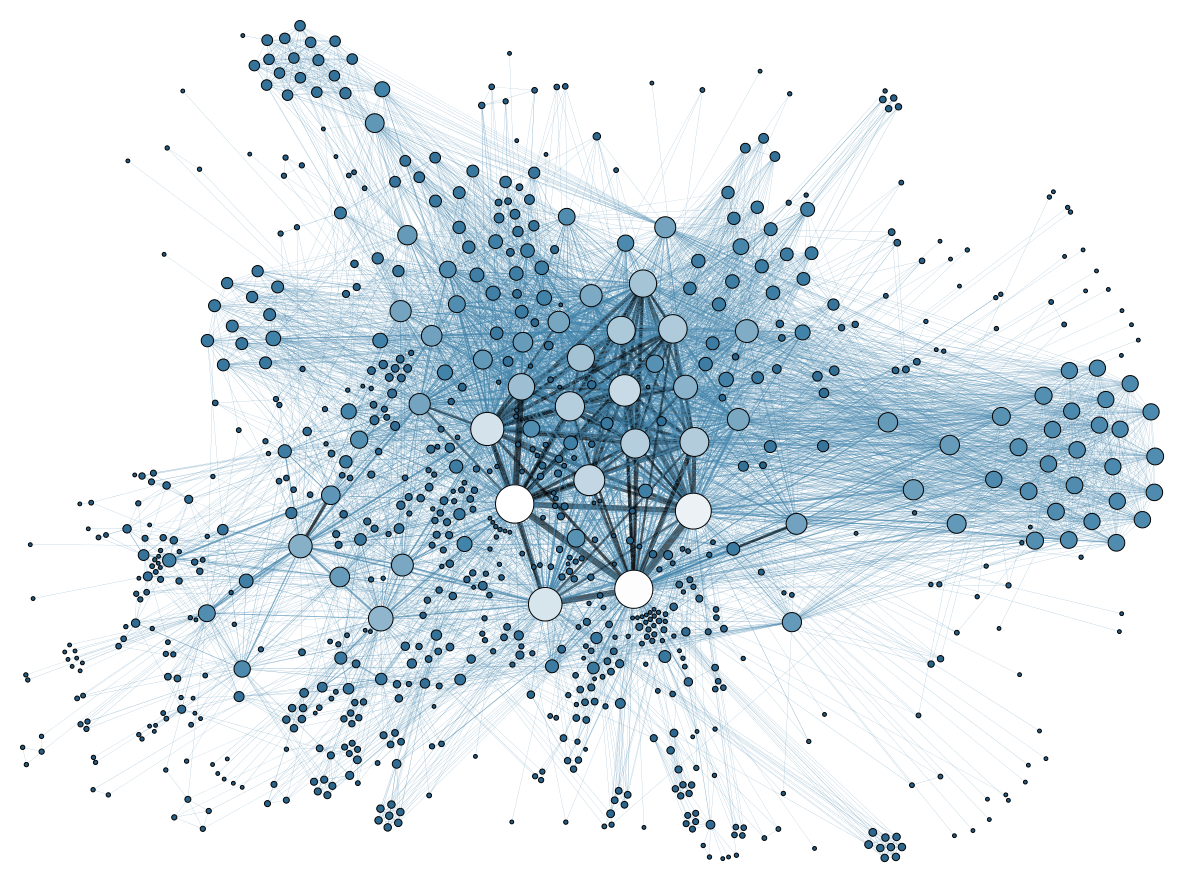

In an ongoing series of posts on the EMiC blog, we’ll be talking about where we are now, how EMiC helped us get here, and how we view the relationship between digital humanities scholarship/training and the #alt-ac and #post-ac tracks. But to get us started, I’d like to feature an article by one of my #alt-ac icons, Katina Rogers, who started out as a PhD in Comparative Literature at the University of Boulder, and is now the Managing Editor of MLA Commons, the MLA’s alternative digital press and scholarly network. You might already know it, or its sister MediaCommons, started by Kathleen Fitzpatrick and the home of Bethany Nowviskie’s #Alt-Academy project. In her recent essay for #Alt-Academy, “Discerning Unexpected Paths,” Katina explores her own journey into the #alt-ac world, and her work with the Scholarly Communications Initiative in analyzing how others like me have ended up there with her. As Katina notes, “The problem with signposts on the alternative academic track is that they aren’t where you expect them to be,” which makes the journey both exciting and unpredictable. Instead of the straight line from PhD to t-t, moving onto the #alt-ac track looks rather more like the social network graph above. You can read the entirety of Katina’s essay here, and keep your eye on this space for discussions of the unexpected paths taken by EMiC fellows past and present.

July 3, 2013

DHSI 2013: Visual Design for Digital Humanists

This post is written by Melissa Dalgleish, Katie Wooler, and Kaarina Mikalson.

We’ve been back from DHSI for a few weeks, and it’s only now that I feel like I’ve properly processed what I learned there. This year, I decided to take a less code-heavy course then I did the last few times I attended, and embark upon Visual Design for Digital Humanists. The broadest interpretation of digital humanist applies here, because anyone who works in the humanities and uses a computer (i.e. anyone) would find this course useful.

Like basically every course at DHSI, VDDH suffers from the problem of trying to cram a vast amount of material into five days, and trying to gear that material to people with a wide range of backgrounds and expectations of the course. That, however, is also a strength, since we got an introduction to the principles of design, gestalt theory, color theory, the vocabulary and practice of critique, user experience and interaction, web design, typography and font design, and Adobe design software. But for those who already have a strong background in design theory and Adobe’s Creative Suite software, the class would likely be boring, as the course material is geared towards beginners.

Despite our obviously brilliant and experienced instructors, the course often simultaneously felt like too much and not enough: too much to learn, too much emphasis on some topics and not others, too little time to put what we’d learned into practice. As Kaarina notes, she didn’t like the over emphasis on critique and communication with designers. Too often, class time veered off course into a discussion between the three instructors as experienced designers, and she easily lost track of the conversation.

But despite its shortcomings, in the weeks after DHSI I realized just how much I’d learned. I submitted my personal blog for a professional critique, and when opinion came back, realized that it wasn’t anything I didn’t already know. I reformatted my dissertation, and recognized while I was doing it that I was applying principles of communicative design I’d learned at DHSI. And I returned to the splash page for my digital edition with fresh eyes and a new sense of what it should look like and what its aesthetics and layout could do. For Kaarina, the course got her thinking about her user personas and what design will best suit their needs. The course also was useful for thinking beyond the material and into the navigation/organization aspects of her digital project, and for giving her some tools and theory for dealing with that shift.

The class is slightly better suited for people who have a designer working for them rather than people who are trying to do the design work themselves, since the course started out with lectures that provided tools for communication with designers and took a little while to get to teaching practical skills. However, the lectures were still a great starting point for DIY-designers as far as gleaning inspiration and being forced to think critically about the purpose of design. In the digital humanities–in all of the humanities–form and function create meaning hand in hand. If you’re interested in enhancing your awareness of how that works on the visual level, or improving your visual vocabulary, VDDH is the course for you.

January 15, 2013

Reporting Back from DHWI 2013

Chris Doody and Melissa Dalgleish were among the six EMiC people (the others were Dean Irvine, Alan Stanley, Vanessa Lent, and Lee Skallerup Bessette) to attend the inaugural year of the Digital Humanities Winter Institute, held at the University of Maryland last week. They all had a great time and wished you were there, although they definitely got more sleep than they do at DHSI because you weren’t. Melissa and Chris wrote a brief introduction to their course at the end of last week, which you can find below.

MD: Chris and I enrolled in Humanities Programming at the inaugurual DHWI, which is wrapping up later today. I enrolled in the course in the hope that learning more about the programming side of digital humanities would be a useful complement to the learning I’ve already done about coding and theory at the DHSI and TEMiC. I’ve been working on learning Ruby since DHSI, but learning a new language on your own is difficult, and I was excited to have some hands-on (and hand-held) time with people who knew it well. And if nothing else, I was hoping that I would learn enough about programming to be able to talk to programmers without sounding like I knew nothing about what they do.

CD: We spent the week learning a variety of programming tools and functions, while working on a building a website, featuring a basic database. I was a little anxious about taking this course, as my only programming knowledge before I started this course was VERY basic html and css. Thankfully, the class was taught by two great teachers–Wayne Graham & Jeremy Boggs (Scholars’ Lab)–who took time to walk through all the steps slowly, explaining as they went, and ensuring that everyone was on the same page. Although I cannot say that I understood every single command that I was entering, I was able to follow the logic of the process as a whole.

MD: Wayne and Jeremy were smart to start with the basics: we spent Monday playing around with HTML and CSS, and as most people are pretty familiar with those, no one left on Monday feeling like their brains were broken. Or at least I didn’t. It helped that we spent at least an hour coming up with excessively (and hilariously) complicated ways to sort out the ordering of lunch. Tuesday was a different story–command line programming was extremely useful, and not too complicated, but once Ruby showed up, things got hard fast. Learning a new programming language is so similar to learning a new spoken language–not only is there a new syntax and grammar to learn, but a huge new vocabulary. And just like my proficiency in picking up new French has significantly diminished as I’ve gotten older, picking up Ruby is neither intuitive nor simple. We took a lot of breaks on Tuesday, because all of us needed a significant amount of time just to process.

CD: So what did we actually do? We started by learning basic Ruby programming vocabulary. After a few hours, we were able to get our computers to say “Hello” to us. After learning these basic functions, we began learning Rails. Our goal was to create a voting system out of a database. We installed some pre-built code into Rails that provided the basic outline of the database, after which we changed the code and CSS to personalize the appearance and function of the database. We were working both locally on our own systems, and then we pushed the website to the “cloud” by hosting the code on Heroku. We were also consistently backing up our code to the online code repository GitHub. Through this simple project, we were able to learn the basics of a large number of tools.

MD: By the end of the week–today–we’d actually made something both useful and nice looking. I’m pretty darn good at keeping the flows of code going between my computer, GitHub (where it’s saved), and Heroku (where it’s hosted and displayed). I’ve gotten a great schooling in best practice in terms of code curation and code sharing. I figured out some basic problems on my own, and I got to have some fun with design. My CSS is getting better all the time, and translating my vision of what a site could look like into code is pure pleasure (when I don’t do it wrong and screw things up). But perhaps most importantly, I’ve gained confidence. Programming isn’t something I need or want to do every day, at least not in my current digital humanities work, but I know that if I needed to do more, I could. It’s more likely that I’ll be called upon to translate my vision of something into terms that someone else doing the programming can act upon, and I’ve got more vocabulary and more knowledge to do that now. And on days when I’m looking for something to do during my downtime, Rails for Zombies is much more fun (and much less frustrating) than it was when I first started playing with it.

CD: In the future, this course would work well for anyone planning on taking the “Text Encoding Fundamentals and their Application” course at DHSI. The introduction to these basic programming functions would lend well to the jargon and formatting that will be learned at the TEI course.

Want to learn basic Ruby? Try this fun course: Try Ruby

Want to learn basic rails with the help of Zombies? Try: Rails for Zombies

If you want to check out what we were working on this week, you can find our sites here:

Chris’s website

Melissa’s website

May 30, 2012

Conversation, Collaboration, Credit: The Graduate Researcher in the Digital Scholarly Environment

Back in the winter, I was lucky enough to find out about the roundable that Daniel Powell was putting together to discuss the role of graduate students who are participanting in large-scale digital humanities projects. The roundtable happened this afternoon at Congress, as part of the SDH-SEMI sessions, and included me, Daniel (UVic), Tara Tompson (UVic), Alyssa McLeod (UVic), Andy Keenan (U of T) and Matt Bouchard (U of T). And as Ray Siemens, among many others, said at the end of our 90-minute discussion, this was one of the most positive, hopeful, laughing, collaborative, and inspiring panels about the state of the profession he’d ever witnessed. Lots of the credit for that goes to Daniel, but lots of it also goes to the excitement and positive energy that characterizes so many DH practitioners, and the field itself. So what did we talk about? And what conclusions did we come to?

1) DH gives us hope. The majority of us considered ourselves both English and DH students—either we were doing concurrent but largely separate DH and traditional English research projects, or were doing literary projects that had a DH component—and since the hiring rate in English is so dismal right now, the feeling that we had other/more options helped stave off some of the angst and hopelessness that so plagues the field right now.

2) But that’s not enough. As we discovered in our conversation, none of us—even Andy and Matt, who have technical knowledge and practical application skills up the wazoo—feel like the work we’re doing in DH as graduate students is enough to get us to the place that we need to be in order to be successful on the job market as DH candidates. A lot of that is because of the divide I mentioned in point 1: we’re literary scholars, and since DH isn’t our core area of practice, we’re less confident about it. We also have to continually justify spending time on it, when it isn’t the research that’s actually going to get us a degree in hand. But we talked about ways to overcome that, like going to play RailsForZombies after we’ve written all we can write for the day, signing up for MITx courses in programming when they open in the fall, pressuring our programs to accept PHP as our second language requirement, and attending DHSI/DHWI. And as Aimee Morrison reminded us, job postings aren’t the be all and end all—hiring committees often don’t know exactly what they’re looking for when they post them, or they’ve posted Frankenstein ads because they’re trying to satisfy a divided search committee. Apply anyway. Just because you aren’t a fully-trained database programmer doesn’t mean that you aren’t what they’re actually looking for.

3) We as graduate students are responsible for what we ask of and take from our DH work, just as our supervisors and PIs are responsible for trying to give us good, varied, and useful work. Let’s face it: RA work, in DH or outside, is often what we termed in our discussion “donkey work,” which in DH is often the same thing as “code monkey” work—the boring, repetitive, isolating work like photocopying, coding, scanning, etc. Some administrative work falls into this category too. It’s unglamorous but necessary, and sometimes only tangentially related to DH as we normally think of it. It’s also problematic for graduate researchers in DH, because getting stuck doing this work day in, day out, with little chance to grow, develop, practice new skills, or learn about the greater workings of large-scale DH projects means that we’re simply not prepared, on graduation, to enter the DH job market. And that doesn’t have to be the case. So as students, we are responsible for advocating for varied, stimulating, and meaningful work, just as our supervisors are responsible to ensure that work is being given to us. Even if it just means that every RA on a project switches roles quarterly.

4) In Aimee Morrison’s words, you need to do twice the work for half the credit. I’m speaking back to point 2. You need to write a dissertation AND put together a digital edition. You need to learn French AND Python. You need to attend ACCUTE AND SDH-SEMI. You need to read Macbeth AND McGann. Yes, it sucks, but at least for now, those are the conditions of being in a dual-focus field like digital humanities—you’ve gotta do the digital and the humanities. Luckily, as Ray Siemens informed us, early career DH professors seemingly have a lower burnout rate than traditional humanities scholars. It’s something, but it’s not enough. If DH is the skill set that departments are looking for, it is also the responsibility of those departments to train us in DH as part of our degrees, for credit, and in the time allocated for our graduate work. If DH is the new theory/research skills/etc., it should be treated as such.

5) We need to start thinking more about what our DH training is for. Just about all of us agreed that we need to be thinking—and we are thinking—about how to take our DH training out into the world beyond academia. But we can’t do it on our own—the field as a whole, and our departments in particular, need to start thinking about how to help us position ourselves on the non-academic job market, and how to help us articulate our skills and knowledge in ways that make sense in the non-academic world. This is of particular importance for terminal MA students, like Alyssa, who may be coming to the degree specifically in order to work outside of academia, but it applies just as much to PhD students. We can’t rely on academia to have jobs for us when we’re done.

6) We need to think more about the relationship between our research and our DH work. Ideally, as with any RA work, the work we’re given will intersect in some meaningful way with our own research interests. We can do more to advocate for work that does so, but we also need to do more thinking about the often artificial split between “intellectual” research and “hands-on” work. I don’t know about you, but I can’t do good work unless I’ve properly researched and theorized how I’m going to do it, and so breaking down that distinction can help us find meaning and purpose in work that might otherwise seem removed from what we think of as academic pursuit.

7) Back to point 1: we are lucky. We are lucky to be working in a field that gives us so many opportunities to learn and develop our skills. We are lucky that there are a number of no- or low-cost ways for us to do so, alongside the paid RA/editorial work from which we learn so much. We are lucky that there are jobs in DH, even if there aren’t in our primary fields. We are lucky that, unlike the “state of the profession” discussion of the Canadian Historical Society in the room next door, our discussion wasn’t all doom, gloom, and whining. There’s a lot of angst and anxiety about being an academic right now, but being a part of the DH community seems to be shielding some of us from the worst of it.

I’m grateful for Daniel for putting this panel together and inviting me to be on it, as I’m grateful to the great crowd of DH folks who packed into a tiny classroom to discuss these issues openly and generously for 90 minutes. We’ll be having a very similar roundtable at Exile’s Return in Paris, and I’m very much looking forward to engaging with the EMiC community on these same issues when we get there. It’s a conversation that we need to have, and to keep having, if the graduate students of today are going to become the digital humanists of tomorrow.

August 15, 2011

TEMiC: Some Thank Yous

TEMiC only lasts for two weeks, but long weeks and months of planning go into making sure that it runs smoothly and successfully. On behalf of everyone who attended TEMiC this week, I’d like to thank the people who made our time at Trent so successful.

Chris Doody: From all of us who participated in TEMiC these past two weeks, we cannot thank you enough. You made sure we were housed, fed, caffeinated, driven around, entertained, exercised, and generally happy. I’m sure it wasn’t the easiest job, but you never made it seem anything less than a pleasure. It wouldn’t have been the same without you!

Zailig Pollock: Thank you so much for volunteering to run TEMiC for another year, which we can only imagine is an exhausting undertaking. We benefitted immensely from your vast theoretical and practical knowledge of what it is to put together a digital editorial project, and I think I speak for all of us when I say that we learned A TON from you.

Our speakers: Alan Filewod, Catherine Hobbs, Carole Gerson, Hannah McGregor, Marc Fortin, Matt Huculak, and Dean Irvine—Thank you so much for travelling to spend time sharing your experience and expertise with us, sometimes long distances to stay for only a few hours. We so appreciate how generous you are with your time and your knowledge.

All of the students who attended TEMiC this summer: Thank you for being so smart, fun, engaged, excited, articulate, prepared, friendly, and just generally awesome. One of the best parts of EMiC is how it brings together like-minded people who are forming a strong and hopefully long-lasting community of scholars. I’m so excited by the fact that I now know (and like!) someone in just about every English department at just about every university in Canada. How cool is that?

August 14, 2011

Diary of a Digital Edition: Part Five [On Modularity]

Having been an English student for more years that I want to count (but if we’re keeping track, nine—yipes!—years at the university level), it’s sometimes easy to feel like I’ve got the basics of being an academic figured out. Much of the time, the learning I do is building on things I already know or refining techniques that I’ve long been practicing. My thinking often shifts and slides, or becomes more nuanced, but I think it would take a lot to completely transform the way I understand, say, Canadian modernism.

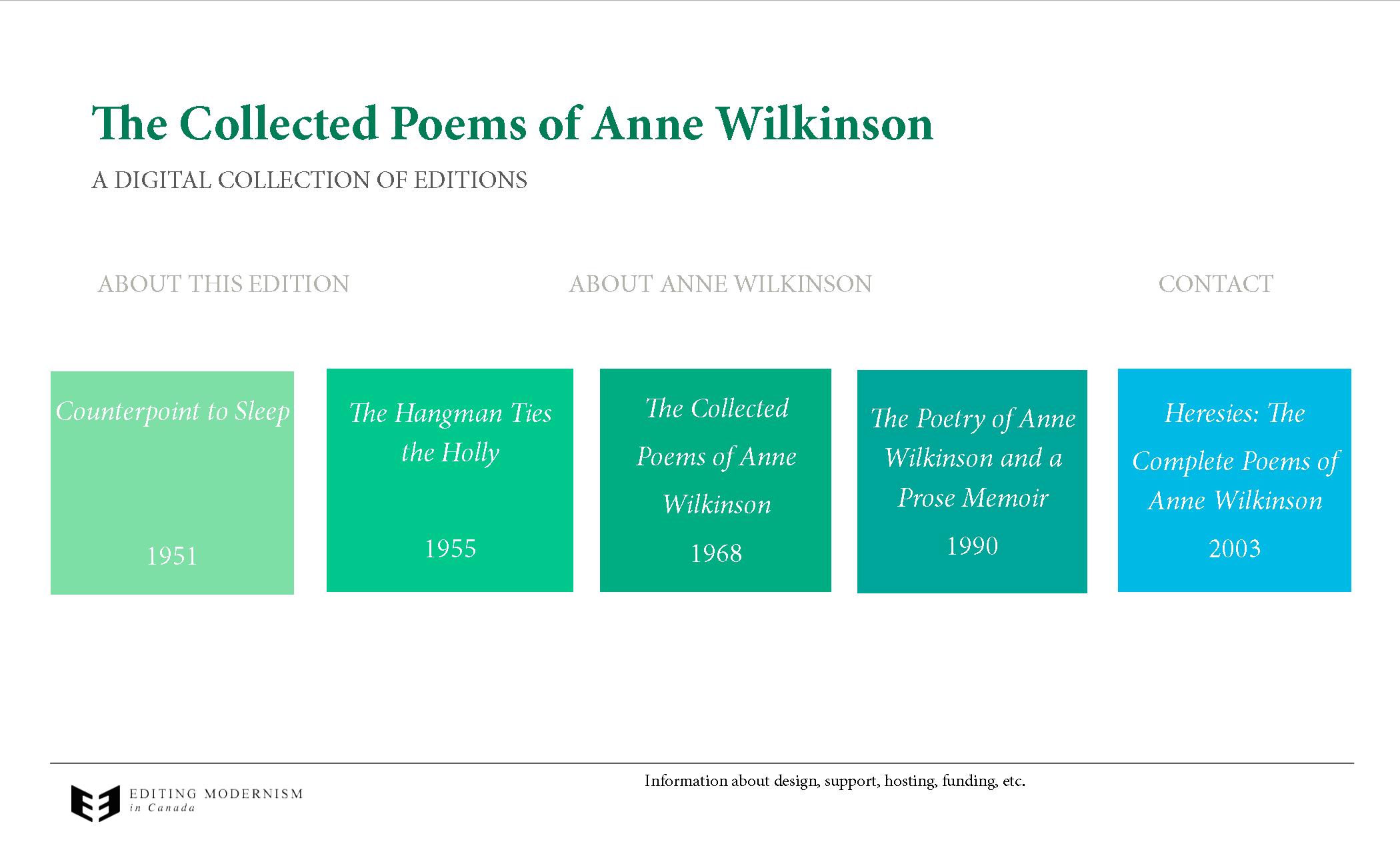

As a DH student, though, those statements absolutely do not apply. Every time I walk into a DH classroom—at DEMiC or at TEMiC, or even just in conversation with other DHers—it’s all I can do to keep up with the ways in which my thinking and practice are continually transforming themselves. The Wilkinson project is a case in point. I started out thinking that I’d be able to do a digital collection of all of her poems—after all, there are only about 150. Then I recognized that facsimiles on their own were inadequate, so the project grew exponentially when I took into account all of the versions—up to 30, for one poem—that I would have to scan, code, and narrativize to create a useful genetic edition. That project was clearly too big to even mentally conceive of right now, so I broke it down into smaller chunks: the 1951 edition first, then the 1955, then the 1968, and so on. Then I broke those chunks down into smaller parts, all the while keeping in view everything I was learning from the EMiC community about DH best practice as I made more and more specific choices about the edition.

As my three weeks in DH studies this summer have made very apparent to me, modularity is now the name of the game (and all credit for this recognition on my part goes to Meagan, Matt, Zailig, and Dean). The idea of modularity is important for my editorial practice, my future as an academic, and my mental health. I always have my ultimate goal—The Collected Works of Anne Wilkinson—in view, but what I used to think of as a small-ish project I now realize will probably take me a decade to completely finish. A more manageable chunk to start with is one module (of probably 10): a digital genetic/social-text edition of Counterpoint to Sleep, Wilkinson’s first collection. Even the first edition, which I’m aiming to have ready for final publication by the time I finish my PhD this time in 2013, can be broken down into smaller modules. First will come the unedited facsimiles. Then, the transcriptions. Then, the marked up facsimiles with their revision narratives and explanatory notes. Each of these modules can be published as soon as they are complete; they don’t represent my final goal for the edition, but they will certainly be useful to readers as I work on the next layer of information.

Modularity makes a lot of sense to me. Counterpoint can be published in the EMiC Commons and go on my CV before I go on the job market, which should help make possible my having the chance to keep working on the Wilkinson project as an academic. By breaking it down, I don’t have to try to mentally wrangle a huge and complex project. And if I hate how Counterpoint turns out, if someone has a really great criticism that I want to act on, if DH best practice changes significantly, or if the EMiC publication engine means that I can do things quite differently, I can completely re-theorize the next edition, The Hangman Ties the Holly, and do quite different things with it. This is especially important when it comes to peer review. If a modernist peer-review body gets created for our digital projects, I want to be able to design my editions so that they will be successfully peer reviewed, and I likely won’t know what those criteria are until after the first edition is done.

The idea of modularity also works quite well for edition and collection design. You’ll note that I’ve given up debating what to call the Wilkinson project, at least for the moment. The individual modules will be called editions, and the modules together will be called collections. I might change my mind later, but rest assured, this will never be called the Anne Wilkinson Arsenal (no offence to Price). I’ve mocked up the splash page for what the Wilkinson collection will look like when the five poetry editions are done.

As you can see, it’s really just a bunch of boxes. And I can have as many, or as few, boxes as I currently have work complete. Those boxes can also become other things as the project gets bigger. In the end, they might say something like Poetry/ Prose/ Life-Writing/ Juvenilia/ Correspondence. They’re endlessly alterable and rearrange-able, which seems to be the core of my new editorial philosophy.

If I can sum up the sea-change that has happened in my thinking about digital editing this year, it’s a shift from thinking big and in terms of product to thinking small and in terms of process. If I didn’t learn anything else, that would be a huge lesson to have grasped. I did learn lots else—the importance of user testing and project design, how committed I am to foregrounding the social nature of texts, how much I love interface design, how much I believe that responsible editing means foregrounding my role as editor and the ways I intervene in Wilkinson’s texts—and I’m looking forward to learning lots more in my hopefully long career as a digital humanist. It’s been a big summer for Melissa as DHer.

There’s a lot I can’t do with the Wilkinson project while Dean, Matt, the PEI Islandora team, and all sorts of other EMiC people work together to get the EMiC Co-op and Commons up and running. It’s just not quite ready for me yet. But there’s a lot I can do: secure permissions for all of the versions of poems that aren’t in the Wilkinson fonds and scan them, create a more refined system to organize all of my files, start writing my editorial preface (very roughly, and mostly so that I don’t forget what I think is most important for readers to know about the edition and my editorial practice), and start narrativizing the revision process of the Wilkinson poems that undergo significant alteration. And (you’ve probably guessed what I’m going to say), I’ll try to make sure that however Islandora turns out, the work I do can be altered and shifted to work with it. It’s going to be a fun fall.

August 8, 2011

The New Week Two: Project Planning at TEMiC, Day One

Week Two at TEMiC looks different this year than it did last and the year before. Rather than being divided between theory and practice, the two weeks at TEMiC are now divided between theory and project planning. During Week One, we plowed through the greatest hits of editorial theory in both text and digital contexts, heard about EMiC projects currently in progress (including work on P.K. Page, Martha Ostenso, and Marius Barbeau), and got a view of the inside of Library and Archives Canada from Catherine Hobbs. This week, we’re taking the theory we’ve learned and applying it to the projects we’re currently planning or working on as EMiC co-applicants and graduate fellows and as undergraduate and Masters students.

We’ve got a fascinating cross-section of participants this week. Today’s post is a run-down of who we are and what we’re working on. Each of us will post about Week Two at some point this week: what we’re learning, the challenges we’ve identified, what we’ve taken from the scholars (Dean Irvine, Carole Gerson, Zailig Pollock, Matt Huculak) who are here to share their experience and expertise in textual and digital editing, and what our projects look like to us on the other side of TEMiC 2011.

As we discussed our projects today, we began to identify the set of challenges and issues that were central to our individual projects but were widely applicable to most of our editorial work. Our goal by the end of the week is to have addressed most of these challenges and to have worked our way as a group toward individual project plans that we can build on when we leave.

Eric Schmaltz is entering his MA year at Brock University under the supervision of Gregory Betts. He is planning a print or digital edition of Milton Acorn and bill bissett’s unpublished 1963 collaboration I Want to Tell You Love as his Masters MRP. Issues & challenges: designing a project that can be completed in a year (with scope to grow afterward); representing a text for which appearance (both type and images) is central; situating a text that straddles the border between modernism and postmodernism.

Shannon Maguire is also entering the Brock MA under the supervision of Gregory Betts. She is planning to work with some of the lesser known publications of Anne Marriott as her MRP–either a Selected Poems edition, or an edition of a specific collection. Issues & challenges: deciding what material deserves renewed editorial attention; designing a project that can be completed in a year (with scope to grow afterward); working with archival material that is located at a distance; deciding what kind of doctoral project to pursue in conjunction with an ongoing editorial project; addressing issues of gender and recuperation in an editorial context.

Melissa Dalgleish is a fourth-year doctoral candidate at York working on the first edition of a larger digital Collected Works of Anne Wilkinson project. Issues & challenges: permissions & copyright; securing assistance and funding prior to becoming faculty; balancing doctoral and editorial work; working on a project that is developing alongside the as-yet incomplete tools that will be used to edit and publish it; addressing issues of gender and recuperation in an editorial context.

Kaarina Mikalson is an undergraduate student at Dalhousie working with Emily Ballantyne and Matt Huculak on the digitization of the French-Canadian periodical Le Nigog. Issues & challenges: thinking through the kinds of editorial work she would like to undertake on her own; representing a text for which appearance (both type and images) is central; editing in French.

Leslie Gallagher is an undergraduate student at Dalhousie who previously worked on Dorothy Livesay’s Right Hand, Left Hand and is now planning to work on Isabelle Patterson. Issues & challenges: deciding what material deserves renewed editorial attention; determining the importance of geography to an author’s work and how to represent that; working with an archive that is located at a distance.

Gene Kondusky is a second-year doctoral candidate at UNB working as a research assistant on Tony Tremblay’s The Selected Fred Cogswell: Critical and Creative, designing the site and interface. Issues & challenges: choosing a markup language (XHTML vs. TEI); defining the purpose of a project–teaching, reading, scholarship; effective interface design; accessibility.

Michael DiSanto is an associate professor at Algoma University working on the war-time letters and collected poems of George Whalley as part of a larger Whalley project that will encompass most of his published and unpublished works. Issues & challenges: permissions & copyright; securing funding; representing a widely varied career and body of work.

We also took a look at Zailig Pollock’s successful SSHRC application for the Digital Page project, and thought about the ways in which we should be conceiving of and representing our projects and project plans. None of us but Michael are at the stage of applying for SSRHC funding, as we’re still at the graduate level, but the kind of thinking required of a SSRHC is the same kind of thinking that will help us create detailed and organized project concepts and plans–and that’s our topic for tomorrow!

May 23, 2011

Diary of a Digital Edition: Part Four

It’s been quite awhile since my last update on the Wilkinson project, largely because a lot of the work I’ve been doing on it has been of the brainstorming, conceptualizing, and theorizing type, and not necessarily of the doing type. Why I didn’t think of that work as bloggable, I’m not sure, but it’s probably something to do with the tendency of many academics to want to share polished work, or concrete work, or complete work—conference papers, articles, books—but not drafts, or notes, or musings. However, the thinking work I’ve been doing over the winter has made me much more able to see the edition as a finished project, and I’ll share with you where that’s gotten me.

Much of this deep-thinking work happened as I wrote an article to submit to the publications associated with last fall’s Conference on Editorial problems, and as I worked on my EMiC PhD stipend application. While my paper at the CEP was about the edition of The Mountain and the Valley that I was acting as research assistant on, I decided to submit a paper on the Wilkinson edition for publication. While the article is more generally concerned with the challenges of putting together small-scale editions like mine, and the conditions necessary for making them a feasible alternative to similarly-scaled print editions, I spent a lot of time thinking about why we would want to encourage the creation of digital editions rather than or in addition to print ones. I love real books as much as the next person, and while I’m relatively tech-savvy, I had originally planned to put together a print edition for EMiC, not a digital one. Why the switch?

Aside from the obvious and pragmatic reasons—a fantastic print edition of Wilkinson’s complete poems already exists, and I couldn’t get permission to do the edition I had earlier planned on—I have one overriding reason for taking on (perhaps foolishly, considering my current workload) the project: because creating a digital Wilkinson edition will let me share Anne Wilkinson’s poetry in all of its uncanny glory, in an accessible and user friendly form, with anyone who wants to read it, anyone who wants to analyse it, anyone who wants to place it in its larger contexts of Canadian modernism, women’s writing, and international metaphysical and mythopoeic poetry. And it can do those things significantly better than any print edition, because it’s free, image-based, infinitely expandable, and can cross-link poems within the collection and across other archives to make explicit the links between Wilkinson’s work and that of others.

Knowing what a digital edition can do naturally leads to thinking about how to design the edition so that it can do these things in the best way we currently know how. As my primary goal for the project is to make Wilkinson’s poetry fully accessible, I then decided that creating an image-based edition was the way to go. Images are easy to view and understand, and capture all sorts of bibliographic information that transcriptions don’t; it will also show people what material exists in her physical archive at the Fisher library, which will hopefully encourage more people to consider both her published and archival work in their research.

Now came a harder decision—how should I organize the hundreds (or thousands—I haven’t counted yet, as it’s a bit scary to consider) of facsimiles that represent all of the variant versions of Wilkinson’s poems? I turned to Dean’s article “Editing Archives ] Archiving Editions” and found a model that made total sense to me—a collection that was an all-encompassing repository of extant and future editions. As Dean argues,

Instead of superseding current critical editions—whether in print or online—or privileging one version or editorial practice over others,…digital archives could potentially enfold any number of critical and non-critical editions into an indexed network in which each edition is experienced as a socialized text—that is, social objects embedded in an apparatus that bears witness to the history of the edition’s production, transmission, and reception. (202-3)

Dean terms a digital archive that enacts this enfolding of editions an “archive of editions” (199), and this is the model I’ve chosen for the Wilkinson project. If my ultimate goal is to make Wilkinson’s work fully accessible, including all of it in a context that allows readers to understand its history of composition, transmission, and reception is essential. This model will allow me to do just that.

But what will it look like? Even I don’t know yet, but here’s how I think of it. Please keep in mind that these imaginings don’t have a lot to do with practicalities of markup and web design, or with the realities of completing this project and a dissertation simultaneously. I might be able to accomplish all of these things, or I might only be able to accomplish a tiny fraction of what I want to. However, I’m thinking big for the moment, and I’ll revise my expectations of myself and the project as it progresses:

Imagine a bookshelf. On the bookshelf, there are five books—Wilkinson’s two published collections, and the three collected/complete editions that were published posthumously, edited by A.J.M. Smith (1968), Joan Coldwell (1990), and Dean Irvine (2003). You “pick up” (click on) her second collection, The Hangman Ties the Holly, and can examine the book’s covers (as high-res images) before opening the book and beginning to read. When you get to the Table of Contents, you have two choices—you can keep reading through, as you would a physical book, or you can click on the hyperlink that takes you to a specific poem. Either way, we have now arrived at a page that contains a poem.

At first glance, this looks like it is simply an image of a page from a book, and you can read it as printed. However, as you mouse over or click on the text, textual and descriptive annotations embedded in the image reveal additional information: explanatory notes, cross-links to other Wilkinson poems (and eventually, to her journals, letters, juvenilia, and prose writing), cross-links to related texts that have a digital presence (this feature will become richer as the writings of more modern Canadian writers are digitized), and textual notes that indicate parts of the poem that exist in variant states.

This is where things get interesting. Somewhere around the page you’re currently reading will be links or thumbnails that represent the images (or recordings) of all of the variant versions of the poem you’re currently reading—from other editions, from periodicals, from typescripts and manuscripts, from her journals, from letters, from anthologies, and from radio or musical performances. I’m not sure how this will work yet, but as a big part of understanding how her texts evolve over time is being able to compare them, you will be able to select and compare two (or possibly more) variant versions of the poem, in facsimile or transcribed form. John L. Bryant, whose fluid text theory I find very intriguing, advocates for the narrativization of textual variation—setting up editions/archives so that they tell the story of how the work changes over time. While I have some concerns about the amount of editorial intervention that narrativization involves—the story can only be told from my perspective, and readers can only trust that I’m telling a “true” story about how the text changes—I do want my edition to allow readers to easily see and understand how the variant versions of Wilkinson’s poems relate to each other and how they change over time in relation to each other. How the edition will do this is something that I still have to do some thinking about.

While this “organization by edition” will encompass many of Wilkinson’s poems, there are a number of published poems that appear only in periodical form, and a number of unpublished poems that only appear in manuscript form. I’m not sure yet how I will organize these; I may decide that The Tamarack Review and Contemporary Verse, among other periodicals Wilkinson published poems in, will have their own “books” on the “shelf” that contain the poems she published in that periodical, and I could certainly do something similar with her copy books. There are obvious issues with this idea, the major one being that periodicals are not books and representing them as such is highly problematic, but again, this is something I need to think further about, and talk to all of you about.

There will also be information coded in TEI that may not necessarily be visible to the casual reader but that will make the Wilkinson collection a rich site for search and analysis—information about the bibliographic features of the texts, formal features of the poems, language use, names and dates, etc. etc. etc. It’s those etc.s that I’m also going to have to do more thinking about—I can’t code everything, even though I might want to (and on an “everything is important” level I do, although on a “I”m on the verge of developing carpal tunnel syndrome” I certainly don’t), and I need to decide what to code based on what’s useful to my project, and what’s useful to the repository more generally when we get to the point of doing cross-collection analysis.

So that’s where I’m at right now; the scanning is done (for the moment–there is more material in the Wilkinson archive at Fisher that I haven’t scanned, but as I don’t have immediate plans to include it in the digital collection, it can wait), the files are almost completely renamed (which is a much more onerous and time-consuming task than I would have thought), and so I’m mostly having fun teaching myself how to use the IMT and waiting to head to Victoria and start the Digital Editions class to figure out where to go from here. I can’t wait!