Archives

Archive for June, 2014

June 7, 2014

What Does Collaboration Mean?

This week I attended the CWRCShop course, “Online Collaborative Scholarship: Principles and Practices,” taught (collaboratively!) by Susan Brown with Mihaela Ilovan, Karyn Huenemann, and Michael Brundin of the Canadian Writing Research Collaboratory. Not only has the course further familiarized me with the various tools that CWRC (cwrc.ca) offers, but it’s also given me the opportunity to think deeply about what it means to work collaboratively. I’ve also been working collaboratively this past week: Kaarina Mikalson and Kevin Levangie, two scholars affiliated with “Canada and the Spanish Civil War: A Virtual Research Environment” (a project I co-direct with Bart Vautour), enrolled in the class too.

Clearly, collaboration is important to my work, and to so much of the work that those of us affiliated with EMiC and CWRC do. And yet, throughout our course discussions and demos—from credit visualization to CWRCWriter, from project structures to data curation, and much more—it has continually struck me how important it is to consider the affective side of collaboration. As Susan suggested at one point, to help collaborators work together (in person and at a distance), it’s integral to also spend time together socially. And it’s been awesome for me to get to SCW-nerd out with Kaarina and Kevin, from debating our favourite literary representations of Norman Bethune to giving a choral response to the question of when Canadians began to hold Canadian citizenship (say it with me—1947).

I want to end, then, by echoing Emily Ballantyne’s “Saying Goodbye” blog post (below), with gratitude for the ways in which EMiC and DHSI give us “a very clear and concrete understanding that my work does not exist in a vacuum, that my work is part of a larger whole that has an invested audience and means something to someone outside of my institution and outside of my own head.” I want to end, too, by throwing these questions out to the EMiC community: as we go forward, what does collaboration mean to you? How do you sustain your collaborative mojo when your collaborators are (sigh) far away? And what, to you, is the value of collaboration?

June 7, 2014

DHSI and the Never-Ending Learning Curve of the Digital Humanities

As I sat through a course on GIS this week, learning theories of cartography and the intricacies of software, perhaps my largest takeaway was a reaffirmation of how different a field the digital humanities really is. On Monday 24 students entered the room with wildly varied backgrounds and levels of experience. Some had never forayed into digital research before; others had been teaching DH courses for years. Regardless of their starting point, however, by Friday all had substantially increased their knowledge and some incredible historical and literary mapping projects were already underway. In combination, the universal success of these populations suggests a truth about the digital humanities: the bar to entry is comparatively low, but you are never done learning.

Even more than the end products of this course, the questions that arose throughout the week were indicative of this fact. Questions like: ‘what constitutes data?’, ‘can location names be pulled from a text file automatically?’, ‘how does a database work?’, ‘what are the options for incorporating multimedia into the interface?’, ‘how can I share my work online?’, and ‘does imposing a literal geography change the source information?’. This mix of theoretical and practical queries, the answers to which were largely beyond the scope of a one-week course, stress the need for collaboration and a continual advancement of skills, two core components of digital humanities research. We are in a field where there is already too much to know and technology is ever advancing; keeping up on what you should be learning and who can provide the skills you lack is vital to pursuing progressive research.

The importance of DHSI for supporting scholars in this way is fairly clear. Few of us are in a position to commit to a full-term course, even if we live near a university that has some, but a weeklong intensive is manageable. For many courses, including the GIS one I had the chance to take, it also means being taught by a genuine expert in their area. Perhaps most significant, though, is the scale of the event and the opportunities it offers to network with some 600 fellow students and instructors. These interactions foster cooperative projects and inspire new ideas that might otherwise never arise. For all these reasons this week has taught me just how fundamental DHSI is to digital humanities in Canada and beyond. I was thrilled to be a part of it, and hope that I can join the ranks of annual attendees.

June 6, 2014

Thoughts on the last DHSI

So this was my third DHSI; I did the TEI Fundamentals, Digital Editions, and Out-of-the-Box courses here. The obvious thing that I’ve gotten out of these courses is knowledge about fields and scholars I may otherwise never have encountered. I think my own future applications of DH are more ambiguous than the tangible knowledge I’ve gotten out of these classes. It’s a good kind of unsteady footing, learning new ways of doing things I’ve already done or I may want to do. The past week was “word frequency analysis,” which was brand new to me. I was thinking about some of the things I might do with it, but in broad, loose ways—most of the work we did in class was on the traits of individual authors or characters in novels, etc. One thing that I’d been thinking about, though, was the traits of authors over the course of their careers; how, for instance, might the letters of an author in his 20s compare to the letters he wrote in his 70s?

The other thing I’d been thinking about this week builds on what Emily talked in her post re: community building. There is, of course, a really beautiful community we’ve built through DHSI in and outside of classes. But the other thing I’ll pull out of DHSI is being able to bring some of the things that allow communities to take shape back to my home institution. Many of the undergraduates and graduate students I’ve taught know little or nothing about DH or DHSI, and so to build into my teaching ways of making my students more aware of such things…that’s really valuable for them and for me. I’m planning on bringing some of what I’ve made in-class here to the Intro to Lit Studies course I’m teaching next fall, just to show first-year students what DH is and what it can do. I’d be really interested to hear how other people might fold their DH knowledge into undergraduate survey classes or other courses.

So, thanks EMiC, thanks DHSI, thanks sauntering deer (who, after many failed experiments, turned out not to like carrots). Going to miss you all.

June 6, 2014

Saying Goodbye

Endings are harder than beginnings. No matter how worn out we feel at the end of a week of DHSI, we have carefully honed a new knowledge set, and in the process have become part of new networks that reinforce and extend our existing networks and the communities that they foster. The end of DHSI this year is a special ending. Not only is it the culmination, for me, of six years of apprenticeship in the digital humanities, but it is also a marker of an impressive amount of personal, intellectual and communal growth. I can’t help but look back and see how far we have come individually and collectively since our first time here.

I am an affective writer, so I am compelled to write this one last post to acknowledge, but not fully express, the conflicting and overwhelming affective experience that has been DEMiC for me for the last six years. It has been frustrating, exhausting and overwhelming. It has been exhilarating, reassuring and empowering. It has encapsulated so much pain, and so much hope. There really are no words.

The thing that I can most decisively point to and hold onto at this important ending is the community that has grown out of this experience and has taken root. I have strong faith that I know who ‘my people’ are and where to find them. The sense of affiliation and devotion I feel to many of you does not have an end date. It doesn’t have research allocations and it can’t be fully explicated on my CV under the general auspices of professionalization. It is more clannish and less coherent. I guess, it is, at the end of this experience, a very clear and concrete understanding that my work does not exist in a vacuum, that my work is part of a larger whole that has an invested audience and means something to someone outside of my institution and outside of my own head. As a scholar, it also means that I also mean something to someone outside of my institution thanks to this community. Our ground is fertile and it has produced much fruit.

At the end of this last DHSI, I just wanted to take one last opportunity to celebrate and mourn this wild journey we have undertaken. Thank you to everyone who has been a part of this project and this community during a formative period in the lives of so many Canadian literary scholars. Goodbye, DEMiC. Goodbye, DHSI.

June 5, 2014

On Belonging

This post begins long before DHSI.

Last semester, I enrolled in a grad-level Project Design and Management course in another department. My classmates and instructor were super welcoming, and I got to work with the wonderful EMiC graduate fellow Andrea Johnston. But I was regularly asked some variation of this question: “Why are you here?” To be clear, this question was asked with respect and genuine interest. Nevertheless, it was a question that I found challenging. The experience was entirely new to me, and I struggled not only to complete the work and learn the concepts but also to justify this training to myself.

When I arrived at DHSI, the question was waiting for me. “Why are you here?” This time, I was fresh out of my first day of the CWRC-run course on Collaborative Online Scholarship, and I answered with an unexpected level of confidence and enthusiasm (read: a shameless brag). That first day of DHSI was enough to refuel me. I has already met a diversity of scholars with a broad range of projects. And though many introduced themselves with a sense of trepidation, it was immediately clear to me that regardless of discipline, experience, or skills, they all contributed to the fantastically generative and invigorating space that is DHSI. We may not all feel in our element, but this community is better and stronger with each of us in it.

DH has an openness about it that I aim to emulate. I do not want to be limited by my formal education, my professional experience or even by my own passions. I want to develop amid diverse communities, not in isolation. This world is terrifically unstable, and I do not just mean economically. I hope to meet the challenges it throws at me, and for now that means actively seeking out challenges

I could bring this down to a practical level in so many ways. I could talk about transferable skills, as Melissa Dalgleish and many others have usefully done. I could reflect on the incredible privilege of being here at DHSI, and I invite you to challenge me on this in whatever ways you can. I could talk about how much I have learned this week, how much EMiC, DH, and so many of you have taught me, and how exactly I will apply that knowledge and wisdom. But these are long and, hopefully, ongoing conversations.

For now, I want to dwell in the confidence that DHSI has so vitally instilled in me. I want to actively take responsibility for my scholarship, my labour, and my professional trajectory. So I return to the old question: Why am I here? Because I chose to be. And I chose well.

June 5, 2014

Visualizing the Landscape of Aboriginal Languages

I have spent the last few days in Scott Weingart’s class (scottbot.net) on Data, Math, Visualization, and Interpretation of Networks. We’ve been working on the basics of network analysis and learning some new lingo around networks and visualizations, such as nodes, vertexes, degrees, directed and undirected, weighted and unweighted edges. The tools we have being using, and the questions and discussions that have arisen in the class have been both practical and critical of the concept of network analysis, possible data bias, and semantic generalization. Nevertheless, we’ve forged on in our quest to create the most beautiful, eye-catching visualizations, and have I been able to see the possibilities in reading data differently through network visualization, and have a wider perspective on the concept of networks in general.

I came to the class without a particular project in mind, so once we started working on NodeXL, and I needed to insert data sets into the program, I sought out some data on the statscan site that I thought might be useful to interpret in relation to networks. I found some data related to Aboriginal languages in Canada from a study produced in 2011 and published in 2013: Aboriginal Languages in Canada. As the title of the table suggests, the data represents three main “nodes” – language, province, and concentration of population with regards to peoples with Aboriginal languages as a mother tongue. Although incomplete, the table does offer the possibility to map the data as a network across geopolitical borders to see where language groups could possibly meet at the edges. Here is the graph that was produced using the data from the survey:

The main nodes on the graph are the different Aboriginal languages, and the provinces in which they can be found as of 2011. It is a directed graph, which simply means that the language nodes point to the different provinces to which they are connected by an arrow pointing in the direction of their presence. Some of the languages only point to one province, while others point to multiple provinces. The edges of the graph, the arrows themselves, indicate the population size of those that speak the language in relation to their concentration in the particular province to which the edge points. The graph offers a few possible readings, and a number of problems. It cannot really tell us anything about the historical relationship between the different languages because it is based on data compiled in 2011 about people living with a particular nation-state constructed through colonial practices. It tells us nothing about the linguistic relationship between or amongst the various languages, although it is possible to see that the concentration of Cree and Algonquian-speaking peoples could possibly have linguistic similarities due to their proximity (which is true, but not expressed by the graph specifically).

What the graph does tell us, which might not be made clear simply by reading the data table, is that there are in fact three networks of Aboriginal languages as expressed in the data. The largest network stretches geographically from Quebec to Alberta to the Northwest Territories. On either side, we get two distinct networks of Aboriginal languages that are isolated along the Atlantic and the Pacific. It is possible to read this visualization of the data beyond the numbers – or at least ask some questions about what it is showing us. Why exactly do the coastal nations exist in isolated spaces? Is it possible to argue that coastal dwellers had different social practices that made them less likely to travel far from the coast, and thus have less interaction with other groups? Does the topography of the landscape have an effect on the fact that Northwest Coast First Nations languages do not cross over into Alberta as of 2011? Or is it simply that the data is insufficient, and we are only able to see how colonial practices produced these isolated networks of linguistic speakers through forced assimilation and the reservation system? I’d be interested to hear what anyone thinks about the visualization, and if there are others questions that could be asked by looking at the networks of Aboriginal languages in Canada. Happy DHSI to all!

June 4, 2014

Lessons Learned from Collaborative XSLT

I’m at my first DHSI ever, four years after retiring from university teaching and thirty-two after teaching a summer course at the University of Victoria, where DHSI is being held. In fact, my course, “A Collaborative Approach to XSLT”, is taking place in Clearihue A105, the same building in which I taught Introductory Shakespeare thirty-two years ago. Clearihue A105 is the computer lab, and in 1982, no one would have dreamt of installing a computer lab in a humanities building, because almost no one would have thought that computers could have any real significance in teaching the humanities, let alone doing humanities research. This coincidence of place just brings home to me how far the humanities have progressed, how much they have changed, over the course of my own working life, and how far I have to go to retool for the new research project I’ve chosen for myself.

I’m here to learn about XSLT in order to prepare a digital edition of the diaries of Robertson Davies. At the first meeting of our course, we’re all asked to talk a little bit about our projects, and what we hope to gain from the course. The first speaker chooses her words carefully. She hopes to become conversant in XSLT. All the rest of us pick up on this modest choice of vocabulary, recognizing that the topic is too big, too complicated, to hope for fluency, or ( even more ambitious) expertise, in the space of a five day course like this one.

Day One proves just how true this is. I can more or less keep up with Josh, who does most of the instructing this day, through the basics of XML, but by mid-afternoon, I’m lost. The exercise on creating an XHTML document with rudimentary formatting flummoxes me, and I have no time to consider the following exercise on CSS. I go home tired, and pretty discouraged. But over the course of the evening, I realize that this is all part of the game, that becoming conversant means only that you gain some understanding, not that you crack the code. And I realize too that I’ve begun to understand a few of the basic concepts, even though I can’t complete the exercise perfectly. Maybe tomorrow will be better. Is this what my students in Shakespeare felt like back in 1982? Were the ideas that seemed self-evident to me more like higher mathematics to them? Maybe I’m beginning to gain a better understanding of what it means to struggle for learning, along with a little XSLT. And I decide that’s not such a bad tradeoff.

June 3, 2014

The Art of Conversation: Learning the Language of XSLT

Today, both Chris and I are posting on our experience in XSLT: A Collaborative Approach taught by the father-son duo Zailig & Josh Pollock. Since he will be touching on the structure and style of the class, I thought I’d comment a bit more extensively on one of the core concepts that inform the Pollocks’ approach to XSLT: collaborative dialogue. The goal of the class is familiarization, so that we can learn to ask the right questions and participate productively in conversations with programmers and other stakeholders in computing. Because this class assumes that the DH-er will be working in collaborative settings, it is teaching us how to become stronger collaborative partners. In order to turn our dream DH projects into reality, we need to be able to express what we need and why using the grammar, vocabulary and structure pertinent to rendering it into our desired form. And that when I realized, it is really no different than what you learn in a first year writing class.

Last week, I finished teaching a summer class on writing and composition at the first year level for non-English majors. For many of my students, this would be their one and only English class to check off the writing requirement component of their degree. Ultimately, the goal of my class was to introduce my students to the academy as a variety of intersecting knowledge communities each of which uses its own genre, convention and style to contribute to the current state of knowledge in any given field. I wasn’t trying to introduce them to the conventions of my own community (literature), but rather, to give them the tools that they need to identify and understand the conventions of whatever disciplines each student had individually chosen to pursue. Throughout the last term, I constantly reinforced the idea of decoding: identifying what elements of the message were structural and vocabulary requirements in order to assert that you belonged and could participate within a particular field of knowledge. By the end of the term, they could competently produce a variety of writing in genres pertinent to fields that were not their own, even though they were not specialists. The content wasn’t changing the course of the field, but the apprenticeship was giving them the ability to participate and collaborate in the generation of knowledge inside and outside of their own fields.

In this XSLT class, I am not learning how to be an expert in XSLT. What I am learning instead is far more valuable: I am learning the critical vocabulary I need to be able to communicate my needs as a digital humanist in collaboration with a programmer. During the introductions yesterday, James Neufeld usefully suggested that his goal in the class was to become “conversant” in XSLT; this was a statement that was picked up by numerous others as we said our hellos and introduced our projects. Becoming conversant in a new field of knowledge is about carefully learning genre conventions and appropriate vocabulary. Like my students, I am learning to decode. Instead of learning how to identify the structure and style appropriate to a book review or journal article, I am learning how to decode code. I am engaged in critical acts of reading that are intended to inform critical acts of writing. In the last two days, I have been learning the conventions and vocabulary of a new knowledge community in order to participate in it. I am not looking to master this genre, but instead, I am looking to be able to understand and identify the central components that make up the genre. I am learning the art, style, convention and parameters of communicating in XSLT.

June 3, 2014

“A Collaborative Approach to XSLT” and a Riddle

I just finished my second day in the EMiC-sponsored course “A Collaborative Approach to XSLT.” This is a new offering at DHSI, and it is fairly original in its design—it is team-taught by a father and son duo, Zailig and Josh Pollock. This pedagogical model—with Zailig as the digital humanist, and Josh as the programmer—works really well for the course, which stresses the importance of successful collaboration. The premise of the course is that “few digital humanists have the time or inclination to master the complex details of [TEI] implementation,” and that instead, what a digital humanist should learn is enough basic vocabulary and skills so that they can communicate with a programmer. This course, therefore, practices what it preaches, with Zailig providing concrete examples in which a scholar might use a complex piece of code and with Josh able to effectively answer all of the more technical questions.

Although it is still early in the week, I can confidently state that this is one of the best courses I have taken at DHSI/DEMiC. Zailig and Josh have clearly spent a long time designing and thinking about the best way to teach this course. The course’s structure, so far, has been that a concept is explained followed by a small exercise where the students have to put this concept into practice. Rinse and repeat. After two days, we have run through twelve exercises, teaching (or refreshing) students about: XML, HTML, CSS, XSLT, and XPaths. Although we have covered a large amount of material in two days is large, the method of periodically stopping and practice each concept as we proceed has ensured that everyone understands and is on track.

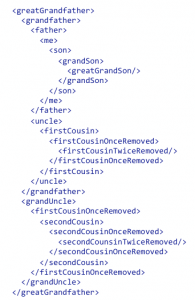

Josh successfully demonstrated how far we have come as a class when late Tuesday afternoon he posted a riddle, and demonstrated how we could solve it using XPaths. For the curious, the riddle is: “Brothers and sisters have I none. This man’s father is my father’s son.” To solve this riddle, you simply need an .xml file and some Xpaths.

count(//me/preceding-sibling::* | //me/following-sibling::*)=0

[Result: true]

//*[.. = //me/../*]

[Result: son]

June 3, 2014

Thinking With Networks

“get to know the people in your class, make new friends, create new connections”

Today I started thinking in a more concerted way than usual about networks: the kinds of networks we form, and the internal dynamics of those networks that may or may not be evident to us. I am, of course, taking the Network Visualization course here at #dhsi2014, and one of the first things we discussed are the patterns and trends toward which social networks tend, including the principle of transitivity (we’re likely to become friends with our friends’ friends) and the tendency for us to reinforce the centrality of those nodes that are already central (do you cite the famous article or the barely known one?).

All this thinking about networks has brought together a constellation of recent thinking for me: the importance of citing one another in our scholarship, for example, and the political exigency of continually expanding our social and professional networks such that we do not shut out other people. But most of all it has me thinking about the urgency and the value of connection.

Network theory tells us that we are social creatures, that we tend toward relationship with one another. The energy at this afternoon’s reception and at Smuggler’s Cove later certainly confirmed it. In the face of the isolating impact of institutions and professions, friendship can be a radical act. I am hoping that, as I think through my own network visualization project, I can conceptualize ways to emphasize the idea that not all networks exist equally. But I am also hoping that this thinking about, and with, networks will keep reminding me of the way that my self and my research is only a single node within a complex web of scholarly collaboration and personal interconnection.