Archives

Archive for August, 2011

August 23, 2011

George Whalley Website: www.georgewhalley.ca

Back in June, after returning from Fredericton, I wrote a brief overview of my work on George Whalley. I mentioned that the production of a website – intended as an introduction to Whalley’s life and writings – was underway. The first iteration of the site at www.georgewhalley.ca was published today.

Robin Isard, the Systems Librarian, and Rick Scott, the Library Technologies Specialist in the Wishart Library at Algoma U, contributed their programming expertise and helped produce a clean and attractive design. The website includes Whalley’s essay, “Picking Up The Thread,” three poems, and previously unavailable recordings of Whalley reading his poems. It also includes unpublished photographs from the beginning to the end of his life, a comprehensive bibliography, and a timeline of significant events in his life. Three essays written by John Ferns (Professor Emeritus, McMaster University) explore Whalley’s life, poetry, and Coleridge scholarship.

This is an important start in establishing a space for Whalley on the web. The site will also help me with my future work in a number of ways. Now, when someone asks me, “What are you working on?” or “Who was George Whalley?” (though Zailig Pollock assured me “surely everyone knows George Whalley”), my answer will end with “and you can see more at www.georgewhalley.ca.”

This is only the beginning. Attending TEMiC has inspired me to reconsider my work and develop a new plan for publishing editions of Whalley’s writings. In the future, the site will include much more material. It may also serve as a gateway to digital editions of Whalley’s writings that will include images of Whalley’s wartime letters and poetry manuscripts and typescripts. The digital editions will be counterparts to print editions. An online database recording the materials available in various archives will also help others who are interested in studying different aspects of Whalley’s works.

I hope the site will spark a renewed interest in Whalley’s life and writings and lead people who are interested in him to contact me.

August 21, 2011

Making meaning through digital design

I feel very fortunate in having been able to attend the Digital Humanities Summer Institute in Victoria for a second time with EMiC colleagues, and in having had the opportunity to take part in the first iteration of Meagan Timney’s Digital Editions course as part of DEMiC. Other EMiC-ites have written eloquently about the various DHSI workshops and how awesome they are, so although I share their enthusiasm, I won’t recapitulate that subject here. Instead, I thought it might be worth drawing attention to a recent article in Literary and Linguistic Computing which resonates with much of what we were talking about at DHSI: Alan Galey and Stan Ruecker’s “How a Prototype Argues”, LLC25.4 (Dec 2010): 405-424.

Galey & Ruecker’s basic proposition is that a digital object can be understood as a form of argument, and indeed that it is essential to start thinking of them in this way if they are to get the recognition they are entitled to as forms of scholarship. Interpreting scholarly digital objects – especially experimental prototypes – in terms of the arguments they are advancing can be the basis on which to peer review them, without the need to rely on articles that describe these prototypes (413). They set out a checklist of areas which could be used by peer reviewers, and also consider the conditions under which peer review can happen – that a prototype reifies an argument, for example, rather than simply acting as a production system.

What I found especially useful in Galey & Ruecker’s piece was the idea of understanding digital artefacts in terms of process. As they point out, this is a point of commonality for book historians and designers, as both are interested in “the intimate and profound connections between how things work and what they mean” (408). Book historians, for instance, situate authoring in the context of multiple meaning-making activities – designing, manufacturing, modifying, reading and so forth – so that it becomes only one process among a plethora of others which together act to shape the meanings that readers take away. Similarly, a range of processes shape the semiotic potential of digital objects. One thing the Digital Editions course did was to force us to think about these processes, and how our editions (and the online furniture surrounding them) would be traversed by different kinds of users. This involves asking yourself who those people will be: see Emily’s fabulous taxonomy of user personas.

However, the act of designing a digital edition is not just about the process of creating an artifact. It’s also a process of critical interpretation (though cf. Willard McCarty’s gloss on Lev Manovich’s aphorism that “a prototype is a theory”). For Galey & Ruecker, digital editions not only embody theories but make them contestable:

By recognizing that digital objects – such as interfaces, games, tools, electronic literature, and text visualizations – may contain arguments subjectable to peer review, digital humanities scholars are assuming a perspective similar to that of book historians, who study the sociology of texts. In this sense, the concept of design has developed beyond pure utilitarianism or creative expressiveness to take on a status equal to critical inquiry, albeit with a more complicated relation to materiality and authorship. (412)

Having spent the week at DHSI getting my head around the intersection of scholarly inquiry, design, and useability, and discovering how exhilarating it was to think about the texts and authors I work with using a completely different conceptual vocabulary, I couldn’t agree more with this: this is intellectual labour on a par with critical inquiry. Thinking about how a user will proceed through a digital edition is every bit as crucial as planning how to construct a conventional piece of scholarship such as a journal article: both involve understanding how to lead your reader through the argument you have built. It’s also daunting, of course, when you have no training in design (and run the risk of getting it spectacularly wrong, as in this salutary warning that Meg & Matt put up in the Digital Editions course). And where the time to learn and think about this fits onto already crowded professional plates I’m yet to figure out, though this is something of a perennial question for DH research. But, I’m also delighted that at this point in my career I have the opportunity to bring in a whole new realm – design – as part of the process of constructing an edition.

One of the reasons it’s important to pay attention to the design of an artifact, Galey & Ruecker assert, is that it has something to tell us about that artifact’s role in the world. While I have certainly thought about the audience for my own digital edition, and the uses to which users might put it, I had not really considered this in terms of my edition’s “role in the world”. The mere act of building a digital edition is an assertion that the material being presented is worth paying attention to, but beyond this there are three further aspects of a digital artifact that Galey & Ruecker suggest as criteria for peer review, which they take from Booth et al.’s (2008) three key components of a thesis topic: being contestable, defensible, and substantive. So, I also have to ask myself: What, exactly, is my edition of correspondence contesting? How am I defending the choices I have made about its content, its form and every other element? And how is it substantive? (These could be useful questions with which to structure the “rationale” part of a book or grant proposal.)

If it’s clear, then, that interfaces and visualization tools “contain arguments that advance knowledge about the world” (406), then the helpful leap that Galey & Ruecker make is to connect this observation to peer-reviewing practices, and to suggest that part of the peer review process should be to ask what argument a design, or a prototype is making. “How can design become a process of critical inquiry itself, not just the embodiment of the results?” (406), they ask, and this seems to me to be a question that goes to the heart not just of our various EMiC editions, print as well as digital, but also of the DEMiC Digital Editions course itself. A great deal of time and effort will go into our editions, and if print-centric scholarly appraisal frameworks aren’t necessarily adequate to all digital purposes then it’s important that we take the initiative in beginning the conversations which will determine the standards by which our digital projects will be reviewed, which is precisely what Galey & Ruecker are concerned to do. As they point out, digital objects challenge hermeneutic assumptions which are anchored in the print culture and bibliographic scholarship of the past century (411). One of the difficulties DH scholars face is when our work (and our worth) is assessed by scholars whose own experiences, training, practices and so forth are grounded in print culture, and who see these challenges not as challenges but as shortcomings, errors, and inadequacies when compared to conventional print formats. The onus, then, is on us to be clear about the arguments our digital objects are making.

I am left to wonder: What argument is my digital edition putting forward? What about those of other EMiC-ites: What arguments are your editions advancing? And how can we be more explicit about what these are, both in our own projects, and across the work of EMiC as a whole?

August 17, 2011

Funding Opportunity for CWRC Workshop

Edmonton Launch Workshop

The Canadian Writing Research Collaboratory (www.cwrc.ca) has funds available to assist scholars wishing to attend the workshop in Edmonton at the University of Alberta, on Thursday, Sept 29th 3:30-5:30 (project launch and reception for those who can make it); Friday, Sept 30th, and Saturday, Oct. 1st.

Workshop topics will include an introduction to CWRC, research-related policy discussions, visualization, interface, text analysis tools, debate of editorial matters including authority lists and textual tagging, and an introduction to current platform functionality. Dr. Laura Mandell of Texas A&M University will be addressing us on the topic of visualization and helping to lead our thinking in the area.

Priority will be given to: emergent scholars, those participating in a CWRC project, and those with limited travel funds.

Please send a brief application for support, specifying:

1) that you are applying for support for the Edmonton workshop

2) your name, institutional position or background, institutional affiliation (or if none, then a brief account of your research area and interest in the CWRC project);

3) the project, research interest or activity that you expect participation in the workshop to advance;

4) an estimated budget of expenses, indicating the amount of your request. Accommodation has been reserved at Campus Towers ($133 and $150), and Lister Centre (residences, $109) from Sept. 29-Oct. 2.

Send this information to cwrc@ualberta.ca by August 19 for full consideration. Requests made after this date may still be considered if funds are available.

August 17, 2011

Cultural Histories: Emergent Theories, Methods, and the Digital Turn

Organized by TransCanada Institute & Canadian Writing Research Collaboratory

University of Guelph

March 2-4, 2012

Keynotes: Alan Liu (University of California, Santa Barbara) – Steven High (Concordia)

In both history and literary studies, critical theory and the cultural turn have called into question the role of narratives and metanarratives of teleology and causation, and of monological or hegemonic voices in scholarly constructions of the past. Be it a reading of the problems of the past with an eye to possibilities in the future, a genealogical analysis of the remains of the past,

cultural ethnography channeled through archives, or a critical rendering of a discipline’s formation, historical projects help us understand ourselves and the sites we inhabit at the same time that they can cause ruptures and discontinuities that unmoor familiar regimes of truth and the instrumental and rational models that produce them. Writing cultural history has been

progressively challenged by a range of intellectual developments since the latter part of the twentieth-century. Critical theory and the cultural turn have called into question the roles of narratives and metanarratives, of teleology and causation, and of monological or hegemonic voices in scholarly constructions of the past. The contemporary accelerated pace of change, the ephemerality of eventful experience, and the relentless remediation of representations of events

in the age of digital information networks present new kinds of challenges in relating the present to events of the recent past. The shift towards digital scholarship further complicates historical projects by offering a much larger potential “archive” of sources and new tools for scholarly engagement. The current fascination with the archive and its application to uncommensurable

referents itself points to a sea change in how we engage with, attempt to access, and inscribe the past. Digital tools offer the chance to engage with the past using evidence on a much larger scale, as well as different modes of representation than those possible with print media. Yet engaging with the potential and perils of digital media requires dialogue with “analog” debates over how to engage in cultural history. This conference aims to bring together literary scholars and historians to discuss the impact of recent theoretical and methodological developments in our fields and think of new directions.

This interdisciplinary conference is jointly sponsored by the TransCanada Institute (www.transcanada.ca) and the Canadian Writing Research Collaboratory /Le Collaboratoire scientifique des écrits du Canada (www.cwrc.ca) to foster debate on new modes and methods of history and historiography, especially those employed or theorized by cultural historians, literary historians, and critics.

Examples of topics or questions to be considered:

• Historiography, historicism, and epistemic shifts

• Cultural histories in the context of post/colonialism, diasporas, minoritized communities, and globalization

• Writing about mega events (e.g., Olympics, G20 protests)

• The writing of histories of literature, text technologies, and modes of cultural production

• Digital interfaces for historical argument

• Historicizing critical concepts, or institutional and/or disciplinary formations

• Genres of cultural histories (e.g., literary history, chronicle, biography)

• The histories of cities, of space, or place

• Non-positivist histories, or speculative histories

• Cultural histories of crisis and/or trauma, truth or reconciliation commissions

• Activist historiography

• Archives as sources, as textual constructs, as problems

• Digital archive structures and their implications for cultural history

• Histories of the ephemeral, the popular, or the representative

We invite proposals of no more than 300 words for twenty-minute papers or panel proposals of three or more papers (nontraditional formats such as 10-minute position papers or project demonstrations are welcome).

Organizing Committee: Susan Brown and Smaro Kamboureli (University of Guelph), co-chairs; Catherine Carstairs (University of Guelph); Paul Hjartarson (University of Alberta); Katherine McLeod (Postdoctoral fellow, TransCanada Institute).

Deadline for abstracts: September 30, 2011

Notification of acceptance: October 30, 2011

Submission address: transcan@uoguelph.ca, or

Cultural Histories Conference, TransCanada Institute, 9 University Avenue East, University of Guelph, ON, Canada, N1G 1M8

August 15, 2011

TEMiC: Some Thank Yous

TEMiC only lasts for two weeks, but long weeks and months of planning go into making sure that it runs smoothly and successfully. On behalf of everyone who attended TEMiC this week, I’d like to thank the people who made our time at Trent so successful.

Chris Doody: From all of us who participated in TEMiC these past two weeks, we cannot thank you enough. You made sure we were housed, fed, caffeinated, driven around, entertained, exercised, and generally happy. I’m sure it wasn’t the easiest job, but you never made it seem anything less than a pleasure. It wouldn’t have been the same without you!

Zailig Pollock: Thank you so much for volunteering to run TEMiC for another year, which we can only imagine is an exhausting undertaking. We benefitted immensely from your vast theoretical and practical knowledge of what it is to put together a digital editorial project, and I think I speak for all of us when I say that we learned A TON from you.

Our speakers: Alan Filewod, Catherine Hobbs, Carole Gerson, Hannah McGregor, Marc Fortin, Matt Huculak, and Dean Irvine—Thank you so much for travelling to spend time sharing your experience and expertise with us, sometimes long distances to stay for only a few hours. We so appreciate how generous you are with your time and your knowledge.

All of the students who attended TEMiC this summer: Thank you for being so smart, fun, engaged, excited, articulate, prepared, friendly, and just generally awesome. One of the best parts of EMiC is how it brings together like-minded people who are forming a strong and hopefully long-lasting community of scholars. I’m so excited by the fact that I now know (and like!) someone in just about every English department at just about every university in Canada. How cool is that?

August 15, 2011

TEMiC report: awesome.

I will admit I was pretty nervous before arriving at TEMiC. After all, what does a confused young undergraduate have to offer a group of experienced scholars? I had no idea how many people would be there, what kind of a pace we would learn at and where I could possibly fit in. Of course, I could have saved time and stress if I had taken a brief moment to reflect on how lovely and generous everyone involved in EMiC is and has been to me from the moment I joined the project. TEMiC was no different. Everyone in the small group of grad students and professors was excited to meet me, hear about my project and share their own experiences and plans. I absorbed as much as possible, taking mental notes on everything they told me and still saving energy to enjoy myself as much as possible.

I only attended the second week of TEMiC, a week focused on project planning. For five short and seemingly leisurely days, we learned a great deal, as you can plainly see from my fellow classmates daily reports. The flexibility of the workshop schedule was really our greatest gain, as it gave everyone a chance to bring his or her own concerns up for discussion. As a result, we were able to discuss (seemingly) all aspects of planning a digital editing project, including securing funding, choosing and using scanners, software and programs, negotiating permissions, copyrights and archives in order to enjoy the most freedom with your material, and the time consuming task of digitizing your material. Through presentations by Zailig Pollock and Melissa Dalgleish, we were able to look in depth at projects currently in progress and get a practical sense of the challenges we would all face. Through presentations by Dean Irvine and Matt Huculak, we learned about the theory and work that is currently going into creating of the EMiC Commons and gained an understanding of how our smaller projects fit into huge advancements in the field of modernist studies and digital humanities. On top of all this, we even found time to win Trivia night at the local bar, suggesting that maybe we have the knowledge and determination to achieve it all (or maybe we just know too much about Hulk Hogan and the Beach Boys).

There were a few key things I took away from the week:

-Modularity! Melissa reminded us all just what a huge amount of work a digital edition is. Starting small allows you to accomplish tasks without getting overwhelmed by a huge amount of material and work.

-Paranoia. I had no idea digital files degrade. This is a little terrifying. Back up your work.

-Collaboration. Academics have the resources and interest to help each other out a lot, especially in the relatively new and intimidating world of digital humanities. We discussed how some kind of EMiC mentorship program could really help people get through their projects, but also how collaboration should not be entered into without any kind of guidelines or ground rules.

Although I am still in the dark about some aspects of digital editions, particularly the ridiculous number of acronyms, I am incredibly grateful for the experience and for all I learned. I am really looking forward to putting my newfound knowledge to use and hearing more about the remarkable projects of my EMiC fellows. I am even excited to run some more files through OCR! Kind of.

Special thanks to those at Trent University who put together such a great workshop and drove us around the city.

August 15, 2011

TEMiC – Week 2, Day 5 – Present and Future

August 12 – The last day of TEMiC at Trent University

Morning Session

For the last day, we started with a discussion based on a forthcoming essay by Zailig Pollock and Emily Ballantyne entitled “Respect des fonds and the Digital Page.” To begin, Zailig told us that the essay was ready for press over a year ago and much has changed since then. For instance, his practice of genetic coding has been modified and now differs from the examples offered in the essay. The essay was inspired by Zailig’s SSHRC proposal and conversations with Catharine Hobbs (at Libraries and Archives Canada). Many archival practices and theories, of which editors should be aware but are not, require contemplation. This understanding led Zailig to explore mediation and archaeology in relation to archives. Discursive remarks may be included in the online project to highlight the physical aspect of the archive and the mediation involved in making a digital version of the physical materials.

To reflect on some past practices and current best practices, we selected some websites to view, comment on, and critique. We looked at Woolf Online (www.woolfonline.com) – which is about three or four years old – and discussed the clean design and user-friendly interface. The title is misleading because the website is not comprehensive and only includes a part of “Time Passes” (indicated in the subtitle at the bottom of the home page). The transcription attempts to recreate the appearance of the page. When we looked at the digital images of the manuscript pages, Zailig pointed out that the images of the manuscript pages, typescript pages, and the transcriptions are not well integrated, because users are forced to move back and forth between two screens. No final reading text or genetic transcription is available. The website provides the material for an edition, but doesn’t actually do the editorial work itself. It is a good example of prototyping, of producing a digital edition at one phase (i.e. in terms of functionality). Other things we considered included: users must pass through many levels to get at the materials; the splash page works very well, suggesting a design consultant was involved, but the content management lacks the same detailed focus; usability studies will improve the functionality of the site; website prototypes become the finished products, rather than early test stages that are later redesigned after use; intuitive navigation is crucial (i.e. why is “Stephen Family” placed next to “Gallery”?); and a person unfamiliar with Woolf’s writings may have difficulty navigating the site and.

Next, we looked at the website, based on Versioning Machine, for Baroness Else von Freytag-Loringhoven (www.lib.umd.edu/dcr/collections/EvFL-class/bios.html). The original versioning software dates back about a decade. While different versions of a text may be displayed side by side, there isn’t enough space on the screen to have more than two versions. Again, Zailig pointed out that the website doesn’t offer an edition, but only a transcription that doesn’t do the work of comparison. We looked at the latest version of the site (http://digital.lib.umd.edu/transition) that uses Versioning Machine 4.0. A basic problem is whether or not it is possible to read the display offered by Versioning Machine. It may be that tabs simply offer a superior view. In the newest version, highlighting the text in one version highlights the corresponding or comparable texts in the other displayed versions. An indication of revision points may be a superior way of displaying and it is necessary to provide some sense of direction in terms of the navigation of versions.

We looked at the Shakespeare Quartos Archive (http://quartos.org/main.php) that is developed out of the University of Virginia. There is a proof of concept for a transparency viewer. One question was why none of the tools are available in full-screen. This version doesn’t allow the transparency viewer to be functional, making it an attractive feature that isn’t altogether useful yet.

We also considered another intriguing idea that might, in the future, be modified for textual editing. At Hypercities Beta 2 (http://hypercities.ats.ucla.edu) multiple historical maps may be overlaid as transparencies. While looking at the site, Zailig told us of a simple tool he often uses: a wooden dowel that holds a paper version of the text directly under an electronic version on the screen. By rotating the dowel line by line in front of the lines on the screen, he avoids eye skip and catches more errors. A screen version of this technique may use a second frame very narrowly configured.

One of the key problems with using the word “archive” is the difficulty of representing an author’s entire fonds online: a single scholar is inadequate to the task. Modularity – selecting one particular part of the whole – is a key to developing a satisfactory and usable online version. Working on minutiae, on a very small set of texts, allows for the step-by-step development of technology and tools that work well and meet fundamental needs. These smaller prototypes will contribute to the development of larger and interconnected projects.

Afternoon Session – Dean Irvine’s presentation

What follows here are some important points Dean made during his presentation.

Every editorial project should begin with a sound theoretical reflection on the practices on which the process is based. The process should be to theorize, then to design, and then to implement.

The Commons: EMiC is not producing digital libraries or archives, but a different kind of repository – the digital commons. This is a collective and social production of resources, not attributable to a single creator, but rather to the many different workers who participate in its making. This understanding draws on the work done by Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri in their books Empire (2000), Multitude (2004), and Commonwealth (2009). The commons is predicated on sociality and the production of social goods. The products result from “immaterial labour,” an excess that is available to the commons, for redistribution among those who participate in the commons. Approximately 80% of the participants in EMiC are women and we must think about the gendering of the commons. Commonwealth addresses the gendering of work and argues that the division of productive and reproductive labour breaks down. Hardt and Negri borrow Foucault’s term “biopolitical” – the conditions under which, in capitalism, all elements of life are contained in biopolitics. In the commons the materiality is subordinate to its sociality. All of the immateriality of the work going into the commons is indicative of a broader global process of the feminization of labour.

The large number of women collaborating in EMiC is in no way representative of modernist studies in general. Previous projects have been dominated by male intellectuals. In Canada, female scholars produce the majority of modernist activities. While the majority of co-applicants or leaders of projects are male, the emerging scholars and graduate students are female. In terms of the distribution and allocation of resources, 80% of EMiC’s funds are going to support the work of women. This signals a change in the field because a generation of workers will come into positions or power, thereby transforming modernist studies and digital humanities.

The problem with the term “archive”: The commons is not an archive, though it might reproduce some of the contents of archives. It is two removes away from the institutional archive. We have an intermediary space – a repository of raw materials for the production of editions. This space will be called the “coop” – produced by cooperative labour and openly shared among the participants. From the coop, users may produce digital editions published in the commons. All the participants are buying in: users must contribute to the commons to make use of the material in the commons. Digital objects cannot be exclusively restricted by any one individual or group of scholars; they are available for use by any and all the participants. However, there are issues of permissions and access – some specific objects may be closed, for good reasons. For example, for the P.K. Page project, the availability of the correspondence is crucial for all the other aspects of the project: access to the letters will be restricted to the editors on the Page project. A person who accesses the archive will be expected to contribute by adding new content.

The material of the commons can be transformed and the product can become the intellectual property of the individual user. The restrictions and permissions will be transparent (and roughly equivalent to those usually found in archives).

The Workflow: how we get material into the commons. Here is a brief overview:

1. Scanning: EMiC has little control over the actual scanning – it cannot provide uniform structures or facilities and each institution may be different – which indicates that the beginning is one of its weakest points. There is infinite variability in terms of infrastructure. EMiC is a networking and training project, not an infrastructure project. Everyone should have access through the university libraries to some scanning instrument.

2. Image Correction: the scanned image may not be exactly ready for production or reproduction. Most often, a person is working with Photoshop and correcting the image by cutting unnecessary parts and/or straightening the image and/or adjusting brightness.

3. Ingest Process Diagram: (On the screen Dean displayed an Ingest Process Diagram, which is roughly described in the following comments.) The repository has two parts: the

interface and the database. The database is Fedora, a broadly used open-access repository for storing digital objects. The interface is based on a content management system (CMS) called Drupal. Drupal is a php interface that allows users to manage the content in the Fedora repository. The integration of Drupal and Fedora has been undertaken by digital librarians working out of the University of PEI: it is called Islandora (a project partnered with EMiC). The Ingest Process Diagram represents the current capability of Islandora. A user starts by creating a parent object, an originator, a corrected image file. This is saved in a Tiff format – it has the least amount of data degradation. There is no lossless digital object. (And all digital objects are slowly degrading.)

An object in the repository must be made locatable by attaching metadata to it. This allows users to search for and recall the object from the repository. Users will fill in a form to create the metadata. File upload sounds easy, but it is not. The system is sensitive to the orientation of the objects the user is uploading. At the ingest stage, there must be a level of image detection and rejection. The repository calls upon the image and creates a new digital object. The original digital object will always exist as a backup: the user is never altering the original. The child object goes through an automated character recognition system. Open access Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software should be available by the end of the year. At the metadata stage, users identify the files that go through OCR or bypass the process. Then user does proof-reading and correcting, basic markup, contextual markup, followed by preview on the web and finally publication on the web. With an authority list, the user might automate the markup of some aspects of the image. Currently, the original image is placed beside the transcription on the screen. This is all web-based.

4. Image Markup Tool: the workflow will have a web-based Image Markup Tool (IMT). A desktop-based tool has been integrated into the workflow. This eliminates the necessity of leaving the web-based environment to complete the IMT.

5. Text Editor – CWRC Writer: CWRC is a web-based TEI editor being developed out of the U of Alberta. In an intuitive interface, the user will be able to do the TEI markup, at least partly by using an authority list. An authority list includes everything that the project editors are tagging in the documents. When a certain word has already been tagged, the authority list provides a suggestion based on previously used terms appearing in other documents. The authority list can be pre-populated for all users of the editorial team. The CWRK is an intuitive interface that helps users with TEI and saves time.

6. Collation Tool: An intuitive interface will compare multiple versions of texts. JUXTA (www.juxtasoftware.org) allows users to compare texts and markup variants. Users can also produce a list of variants. The collation tool might do the work of up to 80% of manual labour (and save time). This desktop-based tool will be made into a web version that will be integrated into the Islandora workflow. (Long lists of genetic textual variant lists are unreadable to most readers of a scholarly critical edition. The assumption until now is that other readers can reconstruct other versions of poems from the printed list of variants in the book.)

Visual representations of the commons will be useful. At http://benfry.com/traces/ Ben Fry has created a visual representation of the transformation through time of six different versions of The Origin of the Species. The visualization exists because a variorum edition of the works of Darwin’s works is already available online. The software is open-access. Dean is asking Islandora to include at least one visualization tool. An abstract visualization tool can be supplemented with a literal representation of textual transformation. Stefanie Possavik – www.itsbeenreal.co.uk – has produced visual representations of the transformation of Darwin’s text. The commons can be represented in terms of visual abstraction, such as this example in a video of the Visual Archive: http://visiblearchive.blogspot.com/.

What will an image viewer for the commons looks like? Dean presented a sketch of a proposal for a viewing environment. The same viewer might be used for multiple purposes at different stages of the process of ingestion, markup, etc. Users will use one interface and change the function it performs at each time depending on the present task.

For every piece of the puzzle one part has already been developed. Leveraging code allows EMiC to work with 5 different institutions and a dozen collaborators, all of which are contributing parts to a much larger project. Digital librarians, working in collaboration with software companies, are central to the development of the EMiC commons.

One of our imperatives may be to generate new practices of reading. The field is unstable and quickly changing because of the multitudinous processes of creation, making it difficult for any one person to comprehend its many strands. Each individual will structure a different narrative comprised of a selection of these strands. How does all of this change our pedagogical principles and the way we present literary studies to our students in the classroom.

EMiC is channeling resources to its principle base: a community of scholars and researchers. Rather than an empire, EMiC is building a community collecting the ideas of many or most of its participants and contributors.

The proofs of concept are not set in stone. The prototypes can be shaped to our own ends.

And the presentation ends.

August 14, 2011

Diary of a Digital Edition: Part Five [On Modularity]

Having been an English student for more years that I want to count (but if we’re keeping track, nine—yipes!—years at the university level), it’s sometimes easy to feel like I’ve got the basics of being an academic figured out. Much of the time, the learning I do is building on things I already know or refining techniques that I’ve long been practicing. My thinking often shifts and slides, or becomes more nuanced, but I think it would take a lot to completely transform the way I understand, say, Canadian modernism.

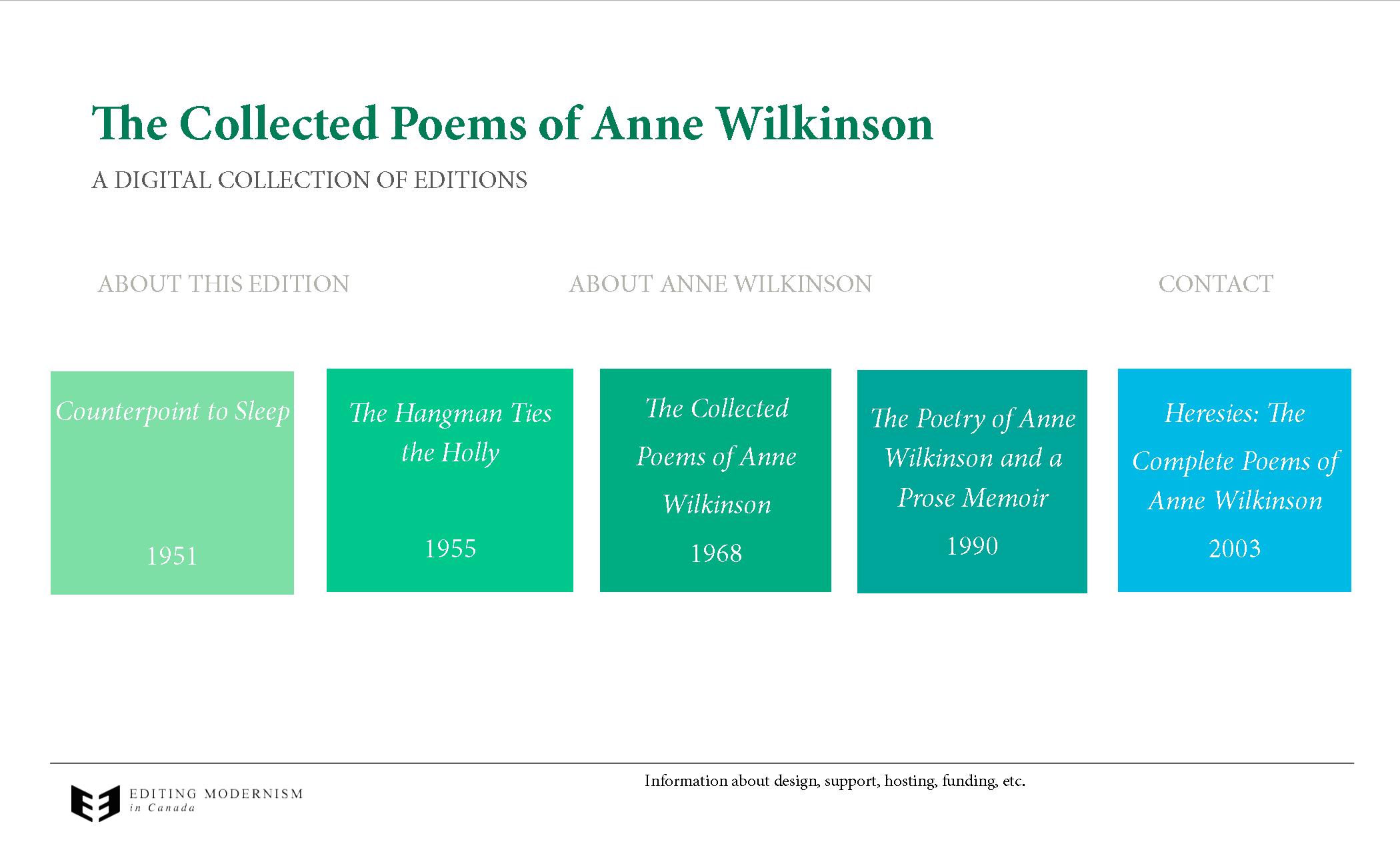

As a DH student, though, those statements absolutely do not apply. Every time I walk into a DH classroom—at DEMiC or at TEMiC, or even just in conversation with other DHers—it’s all I can do to keep up with the ways in which my thinking and practice are continually transforming themselves. The Wilkinson project is a case in point. I started out thinking that I’d be able to do a digital collection of all of her poems—after all, there are only about 150. Then I recognized that facsimiles on their own were inadequate, so the project grew exponentially when I took into account all of the versions—up to 30, for one poem—that I would have to scan, code, and narrativize to create a useful genetic edition. That project was clearly too big to even mentally conceive of right now, so I broke it down into smaller chunks: the 1951 edition first, then the 1955, then the 1968, and so on. Then I broke those chunks down into smaller parts, all the while keeping in view everything I was learning from the EMiC community about DH best practice as I made more and more specific choices about the edition.

As my three weeks in DH studies this summer have made very apparent to me, modularity is now the name of the game (and all credit for this recognition on my part goes to Meagan, Matt, Zailig, and Dean). The idea of modularity is important for my editorial practice, my future as an academic, and my mental health. I always have my ultimate goal—The Collected Works of Anne Wilkinson—in view, but what I used to think of as a small-ish project I now realize will probably take me a decade to completely finish. A more manageable chunk to start with is one module (of probably 10): a digital genetic/social-text edition of Counterpoint to Sleep, Wilkinson’s first collection. Even the first edition, which I’m aiming to have ready for final publication by the time I finish my PhD this time in 2013, can be broken down into smaller modules. First will come the unedited facsimiles. Then, the transcriptions. Then, the marked up facsimiles with their revision narratives and explanatory notes. Each of these modules can be published as soon as they are complete; they don’t represent my final goal for the edition, but they will certainly be useful to readers as I work on the next layer of information.

Modularity makes a lot of sense to me. Counterpoint can be published in the EMiC Commons and go on my CV before I go on the job market, which should help make possible my having the chance to keep working on the Wilkinson project as an academic. By breaking it down, I don’t have to try to mentally wrangle a huge and complex project. And if I hate how Counterpoint turns out, if someone has a really great criticism that I want to act on, if DH best practice changes significantly, or if the EMiC publication engine means that I can do things quite differently, I can completely re-theorize the next edition, The Hangman Ties the Holly, and do quite different things with it. This is especially important when it comes to peer review. If a modernist peer-review body gets created for our digital projects, I want to be able to design my editions so that they will be successfully peer reviewed, and I likely won’t know what those criteria are until after the first edition is done.

The idea of modularity also works quite well for edition and collection design. You’ll note that I’ve given up debating what to call the Wilkinson project, at least for the moment. The individual modules will be called editions, and the modules together will be called collections. I might change my mind later, but rest assured, this will never be called the Anne Wilkinson Arsenal (no offence to Price). I’ve mocked up the splash page for what the Wilkinson collection will look like when the five poetry editions are done.

As you can see, it’s really just a bunch of boxes. And I can have as many, or as few, boxes as I currently have work complete. Those boxes can also become other things as the project gets bigger. In the end, they might say something like Poetry/ Prose/ Life-Writing/ Juvenilia/ Correspondence. They’re endlessly alterable and rearrange-able, which seems to be the core of my new editorial philosophy.

If I can sum up the sea-change that has happened in my thinking about digital editing this year, it’s a shift from thinking big and in terms of product to thinking small and in terms of process. If I didn’t learn anything else, that would be a huge lesson to have grasped. I did learn lots else—the importance of user testing and project design, how committed I am to foregrounding the social nature of texts, how much I love interface design, how much I believe that responsible editing means foregrounding my role as editor and the ways I intervene in Wilkinson’s texts—and I’m looking forward to learning lots more in my hopefully long career as a digital humanist. It’s been a big summer for Melissa as DHer.

There’s a lot I can’t do with the Wilkinson project while Dean, Matt, the PEI Islandora team, and all sorts of other EMiC people work together to get the EMiC Co-op and Commons up and running. It’s just not quite ready for me yet. But there’s a lot I can do: secure permissions for all of the versions of poems that aren’t in the Wilkinson fonds and scan them, create a more refined system to organize all of my files, start writing my editorial preface (very roughly, and mostly so that I don’t forget what I think is most important for readers to know about the edition and my editorial practice), and start narrativizing the revision process of the Wilkinson poems that undergo significant alteration. And (you’ve probably guessed what I’m going to say), I’ll try to make sure that however Islandora turns out, the work I do can be altered and shifted to work with it. It’s going to be a fun fall.

August 11, 2011

TEMiC – Week 2, Day 4: Energy and Inspiration

This morning’s work can easily be summarized with one word: energy. Our session began with Melissa Dalgleish’s discussion of her current work involving the digitization of the collections of Anne Wilkinson. As part of her discussion, Melissa gave a demonstration of an alpha version of her digital interface. I was not alone in being impressed with the elegant, clean, and extensible qualities of the few pages she demonstrated. She also addressed some of the challenges she faces, such as how she intends to label her project (since “archive” and “edition” seem to be misnomers, and “collection” and “collected” both seem insufficient), how she plans to prioritize and organize her data (at which point Melissa re-iterated her principle of modularity; that is, to work with smaller projects that can be incorporated into a larger architecture), and what to do with the vast raw material she has at her disposal.

From Melissa’s engaging talk, our group quickly branched out into a larger discussion of the issues and complexities surrounding digital humanities. Matt Huculak, Dean Irvine, and Zailig Pollock all contributed their vast expertise to the conversation. Zailig highlighted the opportunities stemming from digital representation of original manuscripts, and specifically offered kind words for Melissa’s project and her rationale. Matt stressed the importance of working with reproductions of your original files, while Dean encouraged us to re-consider how we manage our workflow, asking us to take a scientific approach and to offload raw data onto databases, rather than rely on our own machines for data storage. Extending this line of thinking, Dean talked about SourceForge and GitHub, two portals for dissemination of and collaboration with beta versions of software. He reminded us of the importance of sharing our groundwork, so that future scholars needn’t re-invent the wheel every time we begin a new markup project. He pointed to a number of resources, including Juxta, the Versioning Machine, and a proof-of-concept transparency viewer at MITH.

We also talked about the culture surrounding academic work and the spirit of collaboration that typifies the EMiC experience. During the conversation, we all agreed that there is very much a feeling of ‘stumbling around in the dark’ in regards to digital humanities scholarship, which could be remedied (or at least addressed) by further collaboration. However, we also acknowledged that many scholars involved in EMiC already have ample demands upon their time and resources. We brainstormed the possibility of some form of EMiC mentorship program, wherein an experienced scholar or researcher could be asked to mentor a new member of the EMiC community. In this scenario, new members would not only learn the skills already acquired by more senior EMiC community members, but also benefit from the comfort of knowing that it is alright (and normal!) not to start from a position of expertise; indeed, that EMiC’s membership comprises all sorts of skill levels and competencies.

Our afternoon was a lot more free-wheeling. The session opened with a discussion of the idea of co-authorship, and Deans’ sketches for a plan for establishing standards, again drawing upon the scientific model for inspiration. Zailig then talked specifically about his experiences on his various editorial projects, and how he operated as a member of an editorial board, and his views on the role of junior scholars on these boards. He then discussed some other editorial projects, citing what he felt worked well and what didn’t.

Dean then postulated the creation of an EMiC Editions in order to avoid the label of EMiC projects becoming “coterie publications.” He suggested implementing a peer-review process in order to lend more credence to the work produced by EMiC scholars. However, since over a hundred researchers are now involved in EMiC across Canada, he realizes that arms-length peer-review becomes difficult. He suggested that EMiC might need to cultivate relationships with other Modernist organizations, specifically in the United States (although I imagine he would extend his vision globally as well). This, he believes, will foster a greater level of respectability for EMiC, cultivate a common vocabulary for assessment, and create a de-centred model for digital humanities scholarship. In the process of introducing this idea, Dean talked a bit about the history of EMiC, how it has developed as a network and the ways it has evolved since its inception.

Finally, Dean talked about how to fund our research projects. He spoke at length about the idea of leveraging the resources already at our disposal, such as cultural capital and organizational affiliations, and how to use these (and many, many other) resources to succeed in securing funding.

We covered a lot of ground in the afternoon, and I found my mind bouncing from topic to topic. Not that I wasn’t interested in our conversation: in fact, the opposite was true! Again and again, I was jotting down all kinds of notes, half-formed ideas, twists, turns and re-imaginings I might want to incorporate into my own research – and all from the discussion that was generated today! It was fantastic to share the air with EMiC’s zeitgeist incarnate. Dean’s vitality is infectious, and the enthusiasm he imparts, coupled with Zailig’s immense experience and knowledge, and Matt’s incredible expertise, has me feeling inspired, energized, and eager to dive into my research!

Suffice to say, our morning energy carried through to the end of the day, and is likely to carry me forward as I make my way back to New Brunswick at the end of the week, and beyond…

August 11, 2011

TEMiC: “80% of life is showing up [prepared]”

It’s 22:00 (military, airport and Halifax time) on day three of week two, and I haven’t even begun one blog. Goodness, the rest of these TEMiC people are on the ball. Probably helps that they’re well balanced: today we talked about theoretical concepts and their corresponding examples, and were also provided with a generous offerings of clear and technical tips to put us at an advantage when we first embark on digital projects of our own. Additonally, we were encouraged to think about future-proofing our work not only for scholars and readers to come, but in terms of our own professional careers.

Approximately twelve hours ago, we dove into guidelines Zailig Pollock is currently developing for students working on the P.K. Page project, transcribing the work and encoding it with TEI, which in turn can be manipulated in various ways by XSLT to be viewed on the web through HTML. Though the practices he has adopted can not be applied to ever digitization endeavour, it was certainly heartening to see such a clear breakdown of practices. Since his guidelines are still being revised, they are not yet available, but they cover a system of colour coding, symbols, and ways of dealing with issues such as added lines, deleted lines, and illegibility that will ensure consistency in transcription.

The colour coding system demonstrates different versions of the text created by the author, including interventions authored at a later date, as well as the editorial decisions that have taken place. Earlier versions are in red, while final version in black so that this versioning is immediately apparent, while symbols also show where the author has made conscious changes, or simply mistakes which they revised themselves, over a period of time.

The advantage of having both the image of the document and the corresponding markup available online now becomes immediately apparent: by making explicit the choices of the editor, an unambiguous invitation for multiple valid readings is extended to the reader. The editor’s decisions should always be justified, but the ability to return to the text and change things globally, makes it easy to modify editorial decisions with ease.

Along with the decisions of the editor, the creative process of the original author becomes somewhat illuminated.The ability to pull up “incompletes”, or what have been judged to be mistakes on the part of the author, may seem somewhat absurd at first, but it does show off the places where potential for editorial intervention has taken place. The advantage of having both the image of the document and the corresponding markup available online now becomes immediately apparent: by making explicit the choices of the editor, an unambiguous invitation for multiple valid readings is extended to the reader. The editor’s decisions should always be justified, but the ability to return to the text and change things globally, makes it easy to modify editorial decisions with ease. One encoded, the user can pull different scenarios up out of the text, such as lists of emendations, regularizations, genetic views, and the authors own revisions. All of this goes to show the possibility that digitization affords us.

Next we spent some time with an example of P.K. Page’s work coded in oXygen. The basic aim of this kind of encoding is to outline a process, not simply describe the physical appearance of the page and essentially reproduce a transcriptions, but to get at the story behind the process through genetic editing.

Our guest speaker for the afternoon, Dr. Matt Huculak, an EMiC postdoctoral fellow, is concerned with finding and preserving find rare modernist periodicals, which he warns us are currently “dissolving in the archive– literally”. His talk, entitled “Blood on the Tracts: Preparing the Future Archive”, focused on the practicalities of creating the digital archive. It was incredibly pragmatic, (“be useful”, we were told) honest, (addressing the shifting demands of the profession in which we work) and stimulating (discussing the ability to manipulate our data in ways that will serve us no matter where we go in the world, or where the world goes through interdiciplinarity and connecting projects in complex environments).

Apparently, 80% of work in the digital archive is done in preparation. Here’s some quick and easy tips we learned today that will probably save us weeks of work in the future:

Scanning:

-figure out your equipment options, find what is available to you

-always scan as an uncompressed TIFF (avoid compressed formats like jpeg)

-never scan lower than 300dpi.

Backing Up:

be paranoid (so that you don’t have to run into a burning building to rescue your work from the freezer someday) and make sure that you have a backup plan in your workflow. In fact, have three:

-local disk

-backup disk

-cloud

File Naming:

-file naming is for your benefit, so make sure they are sortable according to what you will need.

-file names must be logical, use a heirarchy to name them.

-never put a space in your file name, and always use lower case letters

And finally, my favourite one…befriend a librarian! They know how things work. Also, they’re just cool people.

It’s also important to remember that you can’t do everything–you’re only human ( DHers are not “digital humans”), and you should only be doing work that serves to answer the question that you really want to ask.