Archives

Posts Tagged ‘digitalhumanities’

April 8, 2014

Creating Your Own Digital Edition Website with Islandora and EMiC

I recently spent some time installing Islandora (Drupal 7 plus a Fedora Commons repository = open-source, best-practices framework for managing institutional collections) as part of my digital dissertation work, with the goal of using the Editing Modernism in Canada (EMiC) digital edition modules (Islandora Critical Edition and Critical Edition Advanced) as a platform for my Infinite Ulysses participatory digital edition.

If you’ve ever thought about creating your own digital edition (or edition collection) website, here’s some of the features using Islandora plus the EMiC-developed critical edition modules offer:

- Upload and OCR your texts!

- Batch ingest of pages of a book or newspaper

- TEI and RDF encoding GUI (incorporating the magic of CWRC-Writer within Drupal)

- Highlight words/phrases of text—or circle/rectangle/draw a line around parts of a facsimile image—and add textual annotations

- Internet Archive reader for your finished edition! (flip-pages animation, autoplay, zoom)

- A Fedora Commons repository managing your digital objects

If you’d like more information about this digital edition platform or tips on installing it yourself, you can read the full post on my LiteratureGeek.com blog here.

January 26, 2014

Experimental Editions: Digital Editions as Methodological Prototypes

Cross-posted from LiteratureGeek.com. An update on a project supported by an EMiC Ph.D. Stipend.

My “Infinite Ulysses” project falls more on the “digital editions” than the “digital editing” side of textual scholarship; these activities of coding, designing, and modeling how we interact with (read, teach, study) scholarly editions are usefully encompassed by Bethany Nowviskie’s understanding of edition “interfacing”.

Textual scholarship has always intertwined theory and practice, and over the last century, it’s become more and more common for both theory and practice to be accepted as critical activities. Arguments about which document (or eclectic patchwork of documents) best represents the ideal of a text, for example, were practically realized through editions of specific texts. As part of this theory through practice, design experiments are also a traditional part of textual scholarship, as with the typographic and spatial innovations of scholarly editor Teena Rochfort-Smith’s 1883 Four-Text ‘Hamlet’ in Parallel Columns.

How did we get here?

The work of McKerrow and the earlier twentieth-century New Bibliographers brought a focus to the book as an artifact that could be objectively described and situated in a history of materials and printing practices, which led to theorists such as McKenzie and McGann’s attention to the social life of the book—its publication and reception—as part of an edition’s purview. This cataloging and description eventually led to the bibliographic and especially iconic (visual, illustrative) elements of the book being set on the same level of interpretive resonance as a book’s linguistic content by scholars such as McGann, Tinkle, and Bornstein. Concurrently, Randall McLeod argued that the developing economic and technological feasibility of print facsimile editions placed a more unavoidable responsibility on editors to link their critical decisions to visual proof. Out of the bias of my web design background, my interest is in seeing not only the visual design of the texts we study, but the visual design of their meta-texts (editions) as critical—asking how the interfaces that impart our digital editing work can be as critically intertwined with that editing as Blake’s text and images were interrelated.

When is a digital object itself an argument?

Mark Sample has asked, “When does anything—service, teaching, editing, mentoring, coding—become scholarship? My answer is simply this: a creative or intellectual act becomes scholarship when it is public and circulates in a community of peers that evaluates and builds upon it”. It isn’t whether something is written, or can be described linguistically, that determines whether critical thought went into it and scholarly utility comes out of it: it’s the appropriateness of the form to the argument, and the availability of that argument to discussion and evaluation in the scholarly community.

Editions—these works of scholarly building centered around a specific literary text, which build into materiality theories about the nature of texts and authorship—these editions we’re most familiar with are not the only way textual scholars can theorize through making. Alan Galey’s Visualizing Variation coding project is a strong example of non-edition critical building work from a textual scholar. The Visualizing Variation code sets, whether on their own or applied to specific texts, are (among other things) a scholarly response to the early modern experience of reading, when spellings varied wildly and a reader was accustomed to holding multiple possible meanings for badly printed or ambiguously spelled words in her mind at the same time. By experimenting with digital means of approximating this historical experience, Galey moves theorists from discussing the fact that this different experience of texts occurred to responding to an actual participation in that experience. (The image below is a still from an example of his “Animated Variants” code, which cycles contended words such as sallied/solid/sullied so that the reader isn’t biased toward one word choice by its placement in the main text.)

Galey’s experiments with animating textual variants, layering scans of marginalia from different copies of the same book into a single space, and other approaches embodied as code libraries are themselves critical arguments: “Just as an edition of a book can be a means of reifying a theory about how books should be edited, so can the creation of an experimental digital prototype be understood as conveying an argument about designing interfaces” (Galey, Alan and Stan Ruecker. “How a Prototype Argues.” Literary and Linguistic Computing 25.4 (2010): 405-424.). These arguments made by digital prototypes and other code and design work, importantly, are most often arguments about meta-textual-questions such as how we read and research, and how interfaces aid and shape our readings and interpretations; such arguments are actually performed by the digital object itself, while more text-centric arguments—for example, what Galey discovered about how the vagaries of early modern reading would have influenced the reception of, for example, a Middleton play—can also be made, but often need to be drawn out from the tool and written up in some form, rather than just assumed as obvious from the tool itself.

To sign up for a notification when the “Infinite Ulysses” site is ready for beta-testing, please visit the form here.

Amanda Visconti is an EMiC Doctoral Fellow; Dr. Dean Irvine is her research supervisor and Dr. Matthew Kirschenbaum is her dissertation advisor. Amanda is a Literature Ph.D. candidate at the University of Maryland and also works as a graduate assistant at a digital humanities center, the Maryland Institute for Technology in the Humanities (MITH). She blogs regularly about the digital humanities, her non-traditional digital dissertation, and digital Joyce at LiteratureGeek.com, where this post previously appeared.

November 4, 2013

Infinite Ulysses: Mechanisms for a Participatory Edition

My previous post introduced some of my research questions with the “Infinite Ulysses” project; here, I’ll outline some specific features I’ll be building into the digital edition to give it participatory capabilities—abilities I’ll be adding to the existing Modernist Commons platform through the support of an EMiC Ph.D. Stipend.

My “Infinite Ulysses” project combines its speculative design approach with the scholarly primitive of curation (dealing with information abundance and quality and bias), imagining scholarly digital editions as popular sites of interpretation and conversation around a text. By drawing from examples of how people actually interact with text on the internet, such as on the social community Reddit and the Q&A StackExchange sites, I’m creating a digital edition interface that allows site visitors to create and interact with a potentially high number of annotations and interpretations of the text. Note that while the examples below pertain to my planned “Infinite Ulysses” site (which will be the most fully realized demonstration of my work), I’ll also be setting up an text of A.M. Klein’s at modernistcommons.ca with similar features (but without seeded annotations or methodology text), and my code work will be released with an open-source license for free reuse in others’ digital editions.

Features

So that readers on my beta “Infinite Ulysses” site aren’t working from a blank slate, I’ll be seeding the site with annotations that offer a few broadly useful tags that mark advanced vocabulary, foreign languages, and references to Joyce’s autobiography so that the site’s ways of dealing with annotations added by other readers can be explored. Readers can also fill out optional demographic details on their account profiles that will help other readers identify people with shared interests in or levels of experience with Ulysses.

On top of a platform for adding annotations to edited texts, readers of the digital edition will be able to:

1. tag the annotations

For Stephen’s description of Haines’ raving nightmare about a black panther, a reader might add the annotation “Haines’ dream foreshadows the arrival of main character Leopold Bloom in the story; Bloom, a Jewish Dubliner, social misfit, and outcast from his own home, is often described as a sort of ‘dark horse’“. This annotation can be augmented by its writer (or any subsequent reader) with tags such as “JoyceAutobiography” (for the allusions to Joyce’s own experience in a similar tower), “DarkHorses” (to help track “outsider” imagery throughout the novel), and “dreams”.

2. toggle/filter annotations both by tags and by user accounts

Readers can either hide annotations they don’t need to see (e.g. if you know Medieval Latin, hide all annotations translating it) or bring forward annotations dealing with areas of interest (e.g. if you’re interested in Joyce and Catholicism)

Readers can hide annotations added by certain user accounts (perhaps you disagree with someone’s interpretations, or only want to see annotations by other users that are also first-time readers of the book).

3. assign weights to both other readers’ accounts and individual annotations

As with Reddit, each annotation (once added to the text) can receive either one upvote or one downvote from each reader, by which the annotation’s usefulness can be measured by the community, determining how often and high something appears in search results and browsing. Votes on annotations will also accrue to the reader account that authored those annotations, so that credibility of annotators can also be roughly assessed.

3. cycle through less-seen and lower-ranked editorial contributions

To prevent certain annotations from never being read (a real issue unless every site visitor wishes to sit and rank every annotation!)

4. track of contentious annotations

To identify and analyze material that receives an unusual amount of both up- and down-voting

5. save private and public sets of annotations

Readers can curate specific sets of annotations from the entire pool of annotations, either for personal use or for public consumption. For example, a reader might curate a set of annotations that provide clues to Ulysses‘ mysteries, or track how religion is handled in the book, or represent the combined work of an undergraduate course where Ulysses was an assigned text.

I’m expecting that the real usage of these features will not go as planned; online communities I’m studying while building this edition all have certain organic popular usages not originally intended by the site creators, and I’m excited to discover these while conducting user testing. I’ll be discussing more caveats as to how these features will be realized, as well as precedents to dealing with heavy textual annotations, in a subsequent post.

First Wireframe

In the spirit of documenting an involving project, here’s a quick and blurry glance at my very first wireframe of the site’s reading page layout from the summer (I’m currently coding the site’s actual design). I thought of this as a “kitchen sink wireframe”; that is, the point was not to create the final look of the site or to section off correct dimensions for different features, but merely to represent every feature I wanted to end up in the final design with some mark or symbol (e.g. up- and down-voting buttons). The plan for the final reading page is to have a central reading pane, a right sidebar where annotations can be authored and voted up or down, and a pull-out drawer to the left where readers can fiddle with various settings to customize their reading experience (readers also have the option of setting their default preferences for these features—e.g. that they never want to see annotations defining vocabulary—on their private profile pages).

I’m looking forward to finessing this layout with reader feedback toward a reading space that offers just the right balance of the annotations you want handy with a relatively quiet space in which to read the text. This project builds from the HCI research into screen layout I conducted during my master’s, which produced an earlier Ulysses digital edition attempt of mine, the 2008/2009 UlyssesUlysses.com:

UlyssesUlysses does some interesting things in terms of customizing the learning experience (choose which category of annotation you want visibly highlighted!) and the reading experience (mouse over difficult words and phrases to see the annotation in the sidebar, instead of reading a text thick with highlightings and footnotes). On the downside of things, it uses the Project Gutenberg e-text of Ulysses, HTML/CSS (no TEI or PHP), and an unpleasant color scheme (orange and brown?). I’ve learned much about web design, textual encoding, and Ulysses since that project, and it’s exciting to be able to document these early steps toward a contextualized reading experience with the confidence that this next iteration will be an improvement.

Possibilities?

Because code modules already exist that allow many of these features within other contexts (e.g. upvoting), I will be able to concentrate my efforts on applying these features to editorial use and assessing user testing of this framework. I’ll likely be building with the Modernist Commons editing framework, which will let me use both RDF and TEI to record relationships among contextualizing annotations; there’s an opportunity to filter and customize your reading experience along different trajectories of inquiry, for example by linking clues to the identity of Bloom’s female correspondent throughout the episodes. Once this initial set of features is in place, I’ll be able to move closer to the Ulysses text while users are testing and breaking my site. One of the things I hope to do at this point is some behind-the-scenes TEI conceptual encoding of the Circe episode toward visualizations to help first-time readers of the text deal with shifts between reality and various reality-fueled unrealities.

Practical Usage

Despite this project’s speculative design (what if everyone wants to chip in their own annotations to Ulysses?), I’m also building for the reality of a less intense, but still possibly wide usage by scholars, readers, teachers, and book clubs. This dissertation is very much about not just describing, but actually making tools that identify and respond to gaps I see in the field of digital textual studies, so part of this project will be testing it with various types of reader once it’s been built, and then making changes to what I’ve built to serve the unanticipated needs of these users (read more about user testing for DH here).

To sign up for a notification when the “Infinite Ulysses” site is ready for beta-testing, please visit the form here.

Amanda Visconti is an EMiC Doctoral Fellow; Dr. Dean Irvine is her research supervisor and Dr. Matthew Kirschenbaum is her dissertation advisor. Amanda is a Literature Ph.D. candidate at the University of Maryland and also works as a graduate assistant at a digital humanities center, the Maryland Institute for Technology in the Humanities (MITH). She blogs regularly about the digital humanities, her non-traditional digital dissertation, and digital Joyce at LiteratureGeek.com, where parts of this post previously appeared.

September 25, 2010

Facilitating Research Collaboration with Google’s Online Tools

I’m researching at UBC with Professor Mary Chapman on a project to find as much of the work of Sui Sin Far / Edith Eaton as we possibly can, and wanted to share some of my knowledge around Google’s online collaboration tools and their potential usefulness for digital humanities research. I’d really welcome your comments on anything I’ll discuss here, and I’d love to know: would a Google group for all EMIC participants be a useful thing, in your opinion?

Unfortunately, I really can’t help you with the crucial part of this research: actually finding SSF’s writing. Mary is a cross between a super sleuth and some kind of occult medium, and has a process of finding leads that is as impressive as it is mystifying. Through her diligence and creativity, she’s found over 75 uncollected works by SSF, including mainly magazine fiction and newspaper journalism published all over North America.

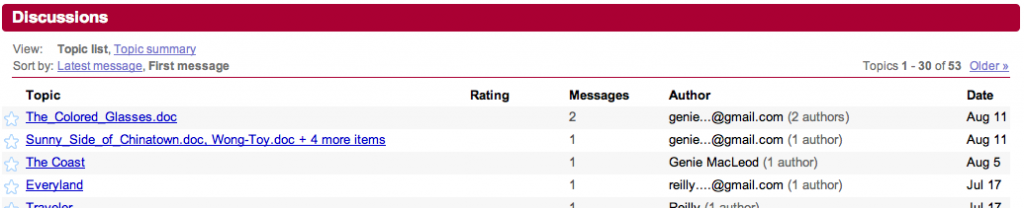

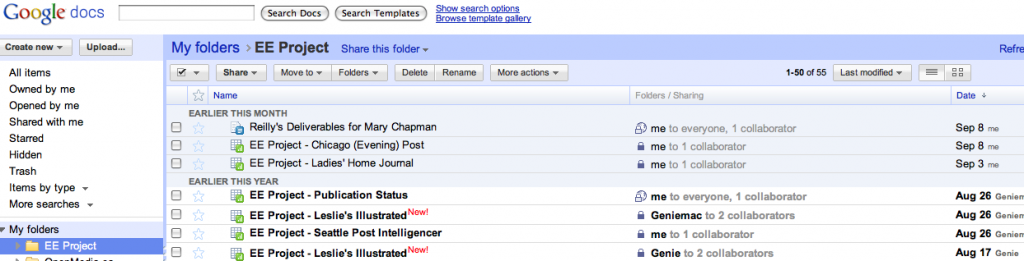

This project has been going on for years; a dizzying number of different people have worked on various aspects of it. When I joined the project in April, multiple spreadsheets and Word documents (with many versions of each one) were the main tools for facilitating collaboration. Each RA seems to have had his or her own system for tracking details on the spreadsheets, so sometimes a sheet will say, for example, that all issues of a journal from 1901 have been checked, but need to be re-checked (for reasons not made clear!)

This represented a terrific opportunity for me, since like most literature students I’m by nature quite right-brained. Working with technology (primarily in the not-for-profit sector) has been a left-brain-honing exercise for me. My brain seems to be a bit like a bird: it flies better when both wings — the left and right halves — are equally developed.

Imposing some left-brain logic on all this beautiful right-brain intuition was actually a fairly straightforward task. First, I set a up a Google group so that current RAs would be able to talk to each other and to Mary:

Creating a Google group gives you an email address you can use to message all members of the group. Then those emails are stored under “Discussions” in the group, leaving a legacy of all emails sent. This is an extremely useful feature – imagine being able to look back and track the thought process of all the people who proceeded you in your current role? It also prevents Mary from being the only brain trust for the project, and therefore a potential bottleneck (or more overworked than she already is).

I then created a series of Google spreadsheets, one for each of the publications we’re chasing down, from the Excel spreadsheets Mary had on her computer. I also created a template – this both sets the standard that each of our spreadsheets should live up to (i.e. lists the essential information, like the accession number, and the preferred means of recording who has checked which issues) and makes it very easy to set up spreadsheets for any publications we discover are of interest in the future.

Finally, I created a master spreadsheet that tracks the status of all our research. More on how that works later on.

In my next post, I’d like to get into some of the specifics of how to use these tools, especially linking the documents to the group. I’d also really like to talk about the efficacy of this system, and the issues it raises: including the fact that, if any Google products (or Google itself) ever go Hal-3000 on us, we’re screwed.

~ Reilly

June 8, 2010

EMiC Love at DHSI

EMiC has been getting some real love in the #dhsi2010 stream on Twitter. For those of you not using Twitter, here are some of the major observations about EMiC that you’ve been missing:

We’re here, and we’re a force:

chrisdoody: Which is more prevalent at #dhsi2010: bunnies or EMiC participants? #emic_project

We’re modelling an approach to pedagogy in the digital humanities:

sgsinclair: #emic exemplary 4 training students & new scholars using experiential-learning pedagogies http://bit.ly/dBPjS9 (expand) #dhsi2010

Our grad students are doing work that is unique and “ambitious”:

jasonaboyd: Hannah McGregor talks about first stages of author attribution study of Martha Ostenso’s work (co-authored with husband?) #dhsi2010 #emic

jasonaboyd: Emily Ballantyne talks about creation of an ambitious critical & interactive digital ed of P.K. Page #dhsi2010#emic

We’re assembling a rich tool kit, an extensive list of partners, and honing our approach:

irvined: A New Build: EMiC Tools in the Digital Workshop http://ow.ly/1VgkZ #emic #dhsi2010

And most importantly, we’re building a community:

irvined: Good luck Emily Ballantyne & Hannah McGregor at #dhsi2010 grad student colloquium. Mila says, “break a leg.” Or “feed me.” Your pick. #emic

isleofvan lunch-hour #dhsi2010 musings on modernism, descriptive markup, and typographic codes http://ow.ly/1VR8P#emic

isleofvan: EMiCites get on the sushi boat in Victoria #dhsi2010 #emic http://yfrog.com/6d4tqoj

MicheleRackham: Great night with #EMiC_project participants last night. Looking forward to a great first day of class. Ready to learn TEI at #dhsi2010

reillyreads: finished orientation sess of #emic @ #dhsi & feel the community vibe growing.

mbtimney: Had a great dinner with the folks from #emic. Hurray, it’s time for #dhsi2010!!

gemofanm: very much enjoyed the non-mandatory “preparatory session” at the Cove at #dhsi2010 with #emic tonight!

Finally, if that’s not enough to get you on Twitter, how about this:

baruchbenedict: I am now doing my first tweet. I owe it all to Meagan.

Yes kids, that’s Zailig Pollock, on Twitter.