Archives

Archive for June, 2014

June 20, 2014

Calls for Papers – Conference in Honour of George Whalley, Queen’s University, 24-26 July 2015

A conference in honour of the centenary of the birth of George Whalley will be held at Queen’s University, July 24-26, 2015. Each one of the three days will recognize different aspects of Whalley’s life and work:

Friday, July 24: Romanticism and Aesthetics: Critical reflections on art, culture and nature

Saturday, July 25: George Whalley, the Man and the Legend

Sunday, July 26: The Canadian Writers’ Conference 60th Anniversary

Participants are strongly encouraged to attend all three days of the event, which will include keynote talks, panels, and papers, as well as a reception and a music performance. The organizers are glad to receive academic and non-academic proposals. Members of the Kingston community and Whalley’s family, friends, former colleagues, and students are all welcome to attend.

The proceedings of the conference, including papers, and possibly audio and video recordings, will be edited and published in an open-access edition online.

A conference website will be available in the near future at www.georgewhalley.ca.

The deadline for proposals sent in response to all three calls for papers below is 31 October 2014.

Day 1, July 24—Romanticism and Aesthetics: Critical reflections on art, culture and nature

2015 marks the 100th anniversary of the birth of George Whalley: poet, war hero, and scholar. In recognition of Whalley’s contributions to the study of British Romanticism through his work on Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and his commitment to “aesthetics, the philosophy of art, and the question ‘What does art convey about reality?’” (Annick Hillger), the Department of English at Queen’s University invites you to participate in an interdisciplinary conference on Romanticism and Aesthetics.

In his now archived notes in preparation for the broadcast of his 1955 television special, “An Introduction to Aesthetics,” a part of CBC’s Exploring Minds series, George Whalley wrote:

“Aesthetics, like any other kind of philosophy, is the affectionate search for truth. The Truth it is looking for is the Truth to do with works of art, and to see how the work of artists fits into the structure of reality, where it belongs in the world, what it does for us, and what it does to us.”

This fragment could serve as an epigraph to Whalley’s career and the critical tradition of “aesthetics” that followed. In the spirit of Whalley’s “affectionate search for truth” we ask now, what is art? How ought one to speak of the experience and value of art—including literary art—without, as Whalley feared, “treating works of art as ‘things’” (Poetic Process) of scientific study. Likewise suspicious of the intrusion of the mechanics of scientific study, Coleridge laments of the imaginative consciousness that “We have purchased a few brilliant inventions at the loss of all communion with life and the spirit of nature” (Lay Sermons). How does one then frame the question in inquiring after the truth-claims or the definition of art? What is the manner and purpose of this inquiry, which we call “aesthetics”? What happens at the intersection of art, culture, and nature?

We invite proposals addressing the following possible areas of study:

a) Symbols in Life and Art

b) The Significance of Poetry to the Romantics

c) Beauty as a Criterion for Definition [: Whither Beauty?]

d) Modern Art Criticism and its Romantic Relations

e) The Limits/ Boundaries of Imagination and Genius

f) Why study “Aesthetics”?

Proposals should be no more than 500 words, and include a brief biography of the presenter(s). They can be sent to Jaspreet Tambar (j.tambar@queensu.ca) and Shelley King (kings@queensu.ca).

Day 2, July 25 – George Whalley, the Man and the Legend

George Whalley (1915-83) was an eminent Canadian man of letters: scholar, poet, naval officer and secret intelligence agent during World War II, leading expert on the writings of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, CBC script-writer and broadcaster, musician, biographer, translator, and president of the Kingston symphony. He taught English at Queen’s University (1950-80), and was twice head of the department. He wrote five books, edited or co-edited eleven other books, and published over 120 essays and reviews. Informed by a life intersecting with important historical events and constant intellectual inquiry, Whalley’s remarkable range of work ranks him with other great Canadian thinkers such as George Grant and Northrop Frye. An introduction to Whalley’s life and works can be found at www.georgewhalley.ca.

We invite proposals for both academic and non-academic papers. Possible topics might include (but are not limited to) Whalley’s:

a) criticism, including his Coleridge scholarship and Poetic Process: an essay in poetics (1953)

b) poetry in Poems 1939-1944 (1946), No Man An Island (1948) and The Collected Poems of George Whalley (1986)

c) The Legend of John Hornby (1962) and/or Death in the Barren Ground: The Diary of Edgar Christian (1980)

d) CBC Radio broadcasts

e) translation of Aristotle’s Poetics (1997)

Papers might also focus on:

a) Whalley as educator and mentor

b) his service in the Royal Navy, the Naval Intelligence Division, and the Royal Canadian Navy Volunteer Reserve

c) his influence on writers and scholars

d) his contributions to Queen’s University

e) public intellectualism after Whalley’s example

Proposals will be no more than 500 words, and include a brief biography of the presenter(s). They can be sent to Alana Fletcher (alana.fletcher@queensu.ca) and Michael DiSanto (michael.disanto@algomau.ca).

Day 3, July 26 – The 60th Anniversary of The Canadian Writers’ Conference

From 28-31 July 1955, the Canadian Writers’ Conference was held at Queen’s University. Co-organized by George Whalley, the conference set out to investigate the state of “The Writer, his Media, and the Public” in Canada, bringing together writers and “representatives of the leading publishing professions, literary critics and the mass media, and an audience of interested people from Eastern Canada” (Whalley to John McClelland, 13 July 1955). The conference, which included public evening talks, morning discussion groups, and poetry readings, featured an impressive slate of Canadian writers, including Earle Birney, Desmond Pacey, Eli Mandel, Anne Wilkinson, Dorothy Livesay, Hugh Garner, James Reaney, Jay Macpherson, Phyllis Webb, Adele Wiseman, Ralph Gustafson, Douglas Spettigue, Miriam Waddington, Irving Layton, Frank Scott, Louis Dudek, A.J.M. Smith, and Morley Callaghan.

The issues raised at this conference, from the “lack of genuinely contemporary Canadian poetry in the school texts” in Canada and a need for cheaper editions of Canadian works (Earle Birney, Writing 47-8), to concerns about “literary criticism in Canada today was inadequate … to the public or to the writer” (48) and “the disappearance of the book” itself (John Grey, Writing 53), have echoed throughout Canadian literary history. The New Canadian Library, the Center for Editing Early Canadian Texts, and Editing Modernism in Canada have sought to address the continuing problem of access to Canadian books identified in 1955, while state-of-the-field exercises like the Calgary Conference on the Canadian novel (1978) recalled the 1955 conference’s debates on whether the Canadian novel could be more than a lesser offshoot of the epic tradition (Douglas Grant, Writing 39).

The 1955 Canadian Writers’ Conference, which was presaged by a 1941 Artists’ Conference at Queen’s and followed by the 1956 Conference on British Columbia Literature at UBC, aimed to bring together a community of Canadian writers, critics, publishers, and readers. In this spirit, we invite proposals for papers to be read during a day of sessions that mark the 60th anniversary of the Canadian Writers’ Conference. We welcome papers on topics including (but not limited to):

a) publishing in Canada since 1955, especially Canadian book series

b) the writer’s function in Canada, the writer as celebrity, and the writer/critic

c) Canadian criticism, its promise, and its pitfalls

d) Canadian literature as publicly engaged or academically cloistered

e) funding for writing in Canada

f) the role of conferences, workshops, symposia, colloquia in building a Canadian literary community

g) the “disappearance of the book,” 60 years later

h) reading in Canada: who reads, what’s read, and why?

We encourage academics and non-academics to submit proposals, and we also welcome offers to read poems or other creative writing. Proposals will be no more than 500 words, and include a brief biography of the presenter(s). They can be sent to Alana Fletcher (alana.fletcher@queensu.ca) and Michael DiSanto (michael.disanto@algomau.ca).

June 20, 2014

New in the Neighbourhood

This year was my first ever experience of DHSI in Victoria, and it has been an awesome whirlwind of activities — meeting so many great people and participating in a lot of the colloquium and “Birds of a Feather” sessions. If I were to sum up the experience in a few words, it might be something like “excited conflict”. There is so much to see and do that it’s a little difficult not to become physically drained and mentally overloaded in just a couple days. Yet, at the end of the week, and even now, I find myself wanting to return for another heavy dose of the same, and wishing it was just a little bit longer.

The Course

I participated in The Sound of Digital Humanities course with Dr. John Barber, along with a few fellow colleagues I work with on a poetry archive project back at UBCO. Throughout the week, the course itself weaved through different focuses, and in between practicing basic editing in Audacity and GarageBand, there was much deep discussion about the nature of sound, theory, research, copyright, and the like. It is especially the latter discussion portion that I was keenly interested in, as we found that some others in the class were doing projects based on or around archives, and were tackling questions and concerns similar to what pertained to our project. It was an opportunity to not only listen and glean some greater insights from experts and generally brilliant minds, but to reciprocate it and impart some of my knowledge to others for application towards their own projects. The general atmosphere is… infectious enthusiasm: everyone is quick to offer their own valuable experiences and suggestions for solutions for others peoples’ projects — in some cases right down to the nitty-gritty technical details. In fact, come to think of it, it doesn’t stray too far from what you might find at a typical medium-sized gathering at a web development conference: some give talks on new cool techniques and technologies, and everyone is engaged in vigorous talk of theory and stories and jokes about working in the field, even over a couple pints at the pub. It was that kind of coming together and collaboration in our class (sans alcohol) which culminated with each of us putting a bit of ourselves into a sound collage representative of the broader aims of the Digital Humanities and our nuanced experiences in it. It was all at times (sometimes simultaneously) hilarious and poignant. Definitely not something I will forget any time soon.

New in the Neighbourhood

In addition to meeting new acquaintances, the week was also a time of reunion, where I was able to reconnect with my colleagues on our poetry archive project. It was a helpful and fun time for us to “regroup” — to reflect on the project’s progress, and also come back with new energy in thinking about ways of moving forward, with the application of some of our discussions both in class and within the larger DHSI hub.. For me, Chris Friend’s presentation on crowd-sourced content creation and collaborative tools yielded wonderful points about the benefits and perils of using such a model pedagogically. It has made me more particularly sensitive to how pedagogical functions might be brought to our archive, and what designs we might create (both visually and technically) to accommodate that.

On a more personal front, attending DHSI (and by extension, learning about the Digital Humanities as a field this year) has solidified a deep sense of belonging for me through moments of glorious serendipity, if you will; of happening upon something fascinating at the end of a long wandering; of searching for a place to call my “intellectual” and “academic” home. It is a place that beautifully brings together my major pursuits of web development, literary theory/criticism, and music, and collectively articulates them as the makeup of “what I do”. It has been one of those somewhat rare “Ah-ha!” moments where you find something that you were looking for all along, but didn’t know quite what it was.

It’s been a wild ride, but one that I definitely want embark on again. My greatest thank yous, all of my friends and colleagues — old and new — for such a wonderful experience. I look forward to when I can return again for another week-long adventure and “geekfest”!

Keep it “robust” my friends.

June 18, 2014

A Breath of Fresh Air

Posted on behalf of Nathalie Cooke:

Let me be candid: DHSI 2014 was a breath of fresh air.

Weather was great, U Vic hosted us with a welcome of trees, breathtaking scenery and wildlife, not to mention hugely friendly staff. My classroom was beside First Peoples’ House, where there was a terrific totem being carved out of cedar. And evenings gave me a chance to visit some of Victoria’s beautiful beaches and glimpse the sea life. Many thanks!

I confess I learned tons of new things at my first DHSI, from teachers, but also from other students since they brought such a range of expertise and interests to this intellectual summer camp for grown ups in a beautiful part of the world. Let me preface my list of things learned by saying that this was my first DHSI, so some of the insights that were huge for me might seem like starlight twinkles from the past for others.

I discovered:

– CWRCwriter (thanks Susan Brown, Michael Brundin, Mihaela Ilovan),

– CWRC mapping tool (thanks Michael Brundin and Susan Brown)

– Voyant tools (on everyone’s list of favourite visualization tools: thanks for the refresher Susan, and huge thanks McGill colleague Stefan and co-investigator Geoffrey Rockwell for imagining and creating this significant application. I’m as impressed now as I was upon first seeing it)

– tweetdeck (thanks André de Avillez)

– storify (thanks André de Avillez)

I was very grateful for luxury of a full workweek in which I could find time to renew collegial links and to establish new ones:

– as well as to explore collaborative work environments (thanks to the CWRCshop itself, and talented & collegial classmates sitting in “my corner” of the classroom, Shakespearean Cameron Butt, fiction author and modernist scholar Claire Battershill, software developer and digital preservation hobbyist Justin Kerk, and Orlando affiliate Kathryn Holand),

– to learn more (thanks Bret and Emily of the Spanish Civil War Project)

– to reconnect with colleagues now living in other parts of the country, including Karis Shearer, Erin Wunker and Dean Irvine

– and even to find a space to catch up with colleagues from Montreal, including Jeff Weingarten, since the usual buzz of academic work leaves few pockets of time for real conversation.

Thanks DEMiC for giving me these opportunities!

June 17, 2014

The Sounds of the Sound of Digital Humanities

I was pleasantly surprised to see Katherine Wooler’s “DHSI Word Cloud” post on June 12th. After Victoria, I certainly do feel “better equipped to create and motivated to co-create with others.” As Katherine’s cloud predicts, “community” and “collaboration” are the terms I want to use to write about my week in Dr. John Barber’s “The Sound of Digital Humanities” class at DEMiC at DHSI 2014.

On the first day of class students were introduced to sound studies and talked about the implications of sound and technology in scholarship and human experience. Each student was given the opportunity to introduce their research interests and describe what they were hoping to take from the class. (This was important because it allowed me, in retrospect, to see how my current project had changed over the course of the week). Later that day we were given tutorials in audio software applications (GarageBand and Audacity). We learned how to sample, mashup, and remix sound files, and spent the rest of the day putting our newfound skills to use, creating sound installations in hopes of generating new ways to think about our research interests (or just make really awesome sounds). Some students worked with recordings they had made themselves (interviews, found sounds) while others worked with recorded materials downloaded from online databases (poetry archives, YouTube). The results were outstanding, and it was unanimously decided that we would start working on a collaborative sound piece to share with the DHSI community at the wrap-up gathering in the MacLaurin auditorium on Friday.

We returned on the second day with energy and inspiration. Despite sunshine flooding the classroom, each student seemed eager to resume working on his or her contribution to the class project, and to discover new ways of thinking about his or her research. While Dr. Barber weaved theoretical information into our discussions (sound and meaning, auditory culture, aural / oral history, sound distribution, sound performance, copyright and fair use), the course had turned (organically) toward creativity, and day three was mostly dedicated to refining our editing skills and using them to rethink our collaborative sound piece. In other words, we were making some pretty cutting sound art. On day four, however, we hit a roadblock. How exactly were we going to present our sounds in the auditorium? Would there be a performance aspect to it, or would Dr. Barber simply press play? Our original idea was to have each student stand up in the auditorium (we would be scattered throughout), laptop in hand, and play his or her file, letting each piece overlap until the whole thing built into a crescendo. While many of us liked the performance aspect, there were a number of problems with it. First, would our laptop speakers be sufficient in a room of that size? Second, would a crescendo turn our sounds into noise? After a lengthy talk we decided to transfer our files onto Dr. Barber’s computer and make a single sound file. We would then be able to use the auditorium’s audio system and give our sounds the volume they deserved. We would lose the performance aspect, but could be sure of a reliable delivery. Alas, there was a third problem. How were we supposed to squeeze fifteen sound files ranging from forty-five seconds to two minutes into a seven-minute presentation? We knew from the start that length was going to be an issue . . . but the crescendo approach would have allowed us to ‘stack’ our sounds and thus decrease the time of the performance. In the end, our sound editing skills (and Dr. Barber’s expertise) gave us a way out. We used GarageBand to import our files, arrange them in what we agreed was the most aesthetically pleasing way, and pare the final product down to an appropriate time.

So here are the fruits. As mentioned, it was played on Friday, June 6th in the UVic MacLaurin auditorium, which most of us missed due to breakfast. Special thanks to the creators: John Barber, Annalisa Butticci, Liza Flum, Deanna Fong, Alice Huang, Penny Johnston, Justin Kroeker, Catherine Kroll, Laura Larsen, Cole Mash, Emily Oliver, Karis Shearer, Robert Stibravy, and David Weston. Thank you for sharing your minds. Lastly, thanks to each and every one who attended DEMiC at DHSI 2014. Thank you for your conversation, encouragement, and kindness. I look forward to our paths crossing again. These friendships will last.

June 15, 2014

In My End is My Beginning

With the support of EMiC I have attended DHSI as a student from the very beginning and have learned an enormous amount – only part of my huge debt to EMiC over the years.

In the course of my years at DHSI, I believe I have set two precedents: I am the first person to have retired since joining EMiC and I am the first EMiCite to have graduated from the status of student to instructor.

Previous to teaching this year’s DHIS/DEMiC course I had taught TEMiC in Peterborough, but while that course dealt to some extent with digital editing its primary focus was editorial theory. The course this year grew out of a text/image tool for genetic editing which Josh and I are in the process of developing (see Chris Doody’s post, The Digital Page: Brazilian Journal ). The course did not focus on this tool, however: its focus was on the XSLT which is the backbone of the tool, and the collaborative process that went into developing it.

We had originally intended to call the course Every Batman Needs a Robin (a bow to another, very successful digital humanities collaboration involving Mike DiSanto and Robin Isard) but we soon realized that this would misrepresent the true nature of our non-hierarchical working relationship. We considered Every Batman Needs an Alfred but that seemed a bit esoteric.

Although Josh and I worked very closely together in planning the course, I was very much his assistant in teaching it, since his mastery of XSLT far exceeds mine. But this was a central thrust of the course. If digital humanists are to succeed in their projects, unless they are highly experienced programmers themselves – which few are, or have the time or inclination to become – it is necessary to establish a strong, personal, longstanding relationship with a developer. Our experience, and the experience of other digital humanist/developer teams, is that the project will take shape as a result of this collaboration, and the shape that it will take is often very different than what the digital humanist who initiated the project had in mind.

My role in the course was twofold: to help students out with the numerous hands-on exercises which we had devised for them (I wasn’t nearly as good at this as Josh) and to act as a kind of stand-in for the students, asking for clarification or repetition of points that were blindingly obvious to Josh but perhaps less so for the non-programmers amongst us. I was obviously much better at this than Josh was.

We had a very wide range of students in the course – from Master’s students to a Professor Emeritus – with a similarly wide range of projects, skills and aptitudes. But, judging by our interactions with the students and the student evaluations we struck a pretty good balance.

Certainly, from my point of view teaching such a committed and intelligent group of students who seem to have genuinely appreciated the work we put into the course, and doing so with my son (we didn’t fight once!) was a great experience – a real high point of my career and life.

I was very pleased to hear, then, that we have been asked to return with the course next year. So one of my many debts to EMiC, as it comes to its appointed end, is that my association with it has marked a new beginning for me – as a DHSI instructor.

June 14, 2014

DEMic/DHSI 2014 One week later

It has been a busy couple of weeks: Congress at Brock University, then DEMiC/DHSI 2014 at the University of Victoria, and a week to process both. The combination has emphasized my schizophrenic academic identity. At Congress, I attended the Canadian Society for Renaissance Studies, the Bibliographical Society of Canada, and the Canadian Society for the Study of Book Culture; at DHSI, although year-after-year part of me gazes longingly at Helene Cazes’s course on the “Pre-Digital Book,” I took the course on “A Collaborative Approach to XSLT” with my longtime collaborator Zailig Pollock and his son Josh, a project manager for Microsoft — in which we were exposed to an extraordinary combination of editorial experience and technical expertise.

Strange as it seems, all of these are absolutely central to my teaching and research. I am currently cutting the manuscript of the selected letters of E.J. Pratt, after which I will be revamping the digital complete letters site originally published in 1998-2002 (http://www.trentu.ca/pratt). This Fall, I will be teaching both Renaissance literature and the “core” course in the Public Texts M.A. Program at Trent University on book culture and book history, a course which surveys “the material and social production of texts and their circulation in relationship to publics, focusing on technological and social practices and the circulation of texts, from preliterate orality through the development of literacy and print to contemporary digital media.” In my own research, I work both with early printed books and digital media. I study records of aristocratic and civic entertainments for Elizabeth I and how they intersect with canonical literature, but I am also an editor of the public and private writing of Canadian modernists — A.M. Klein, E.J. Pratt, and P.K. Page. (The modernists do love initials!) Oddly enough, I do not see this as contradictory. In both cases, I am fascinated with the potential of digital media to preserve the original “material” text and make it available to contemporary readers — to convey the “text” (and “paratext”) in the diverse forms in which it has been “published.” As Zailig Pollock is perhaps Canada’s premier “genetic” editor, this was very much a focus of the course he and his son Josh taught at this year’s DHSI. His own TEI coding and Josh’s XSLT style-sheets are designed to display P.K. Page ‘s composition process — the evolution of the work and its published forms. It is no great surprise that three of the students in his class are editing portions of Page’s “complete works” — Chris Doody, the Brazilian Journals; Emily Ballantyne, the non-fictional prose; and myself, the fiction. However, while we saw what could be done with pages from P.K. Page’s Brazilian Journal, the coding we did before, and then in, class was tied to one of Shakespeare’s sonnets. In both cases, the facsimile is linked to genetic display, and the model is infinitely transferable. That is where the excitement lies.

Many of the blogs posted during and after DEMiC/DHSI have commented on collaboration and community. Since the early 1990s, I have been extremely lucky to have been involved as an editor in “complete works” projects — collaborative projects in which each editor built on the work of those who came before. In these projects, the “letters” volume tends to comes last, so that the editor can allude to volumes containing the published works. However, much of this “collaboration” is after-the-fact. One of the most important features of EMiC has been the development of a wide-ranging community of scholars working on editorial projects related to “modernism” in Canada; and DHSI has augmented that community to include “digital” media. I have attended one TEMiC and two DEMiC/DHSI summer institutes, and the community of scholars to whom I have been introduced has enriched my work in ways which are harder to quantify but extremely productive. In the joint session of two of this year’s DHSI courses — “Online Collaborative Scholarship: Principles and Practices” (a “CWRCshop” taught by Susan Brown et al) and “A Collaborative Approach to XSLT” (sponsored by EMiC and taught by Zailig and Josh Pollock) — the point was made that face-to-face contact changes the game. It really does! Thank you to Zailig and Josh Pollock, Chris Doody and Emily Ballantyne, James Neufeld, Anouk Lange, Karis Shearer, Helene Cazes, Michael Ullyot, Dean Irvine and Alan Stanley, and all the rest.

June 13, 2014

Planning to Learn, Learning to Plan

This June was my fifth consecutive trip to Victoria for the Digital Humanities Summer Institute (DHSI). What makes the week so vital and productive for me is (at least) twofold: I know I will learn some basic skills and I know that research plans are hatched and developed during the week’s activities. When I began what would become a yearly sojourn to Victoria I suspected the former, and now, five years in, I’ve come to expect the latter.

DHSI has shaped my research in some substantial ways. It was at DHSI that I began talking with Emily Robins Sharpe about working together on a project about Canadian involvement in the Spanish Civil War. Each DHSI our project planning develops in leaps and bounds. We’re able to come together to plan, but also to celebrate the successes of the project. This year we were able to celebrate a “proof-of-concept” website [spanishcivilwar.ca] and a renewed mandate for the project.

What have I learned? Project planning is crucial.

No matter how big or small in scale the project is, planning can make or break the project. Part of planning is simply talking with others and asking questions of colleagues old and new: Have you done something like this before? How did you overcome such-and-such obstacle? Does our timeline seem like something we can accomplish? Do you know and researchers who might like to get involved? And the questions continue…

So, do you have a project in mind that needs better definition? DHSI might just be the perfect place to hatch those plans.

Bart Vautour is Assistant Professor (Limited Term) at Dalhousie University.

June 13, 2014

UPDATED: GOODBYE, DHSI

DHSI 2014 is done, and most EMiCites will be heading home tonight or early tomorrow. Many have captured their experience of DHSI—some in Victoria for the first time, others for the last—on the EMiC blog. If you were were too busy XSLTing or doing yoga on the lawn of the cluster housing to keep up, now’s your chance: a roundup of DSHI 2014 blog posts is below. The list will be updated as more posts are published.

Kailin Wright discusses qualitative research at DHSI: http://editingmodernism.ca/2014/06/all-the-people-a-look-at-qualitative-research/

Mathieu Aubin explores community: http://editingmodernism.ca/2014/06/community-formation-demic-2014/

Cole Mash’s soundtrack to “Sounds of the Digital Humanities”: http://editingmodernism.ca/2014/06/island-intersections/

Katarina Anderson on undergraduate involvement: http://editingmodernism.ca/2014/06/encouraging-undergrad-involvement-in-dh/

Katie Wooler visualizes collaborative communities: http://editingmodernism.ca/2014/06/dhsi-word-cloud-the-future-is-collaborative/

Andrea Hasenback gets into GIS: http://editingmodernism.ca/2014/06/making-it-work/

Andrea Johnston celebrates “serendipitous learning”: http://editingmodernism.ca/2014/06/augmented-reality-and-education/

G Jensen reflects on “A Collaborative Approach to XSLT”: http://editingmodernism.ca/2014/06/agile-development-and-the-digital-humanities/

Alix Shield contemplates ethics and ethnographies and the Mukurtu mobile app: http://editingmodernism.ca/2014/06/re-envisioning-digital-heritage-management-mukurtu-and-mukurtu-mobile/

Lee Skallerup Bessette acknowledges the overwhelm that is DSHI Day One: http://editingmodernism.ca/2014/06/dhsi2014-all-the-things-all-the-people/

Hannah McGregor talks network visualization and the role of DHSI in fostering EMiC and DH community: http://editingmodernism.ca/2014/06/thinking-with-networks/

Chris Doody reports back from Zailig and Josh Pollock’s new course in collaborative XSLT: http://editingmodernism.ca/2014/06/a-collaborative-approach-to-xslt-and-a-riddle/

Emily Ballantyne advocates for the the value of vocabulary, not just expertise: http://editingmodernism.ca/2014/06/the-art-of-conversation-learning-the-language-of-xslt/

James Neufeld reflects on the experience of one again being an apprentice: http://editingmodernism.ca/2014/06/lessons-learned-from-collaborative-xslt/

Marc Fortin creates beautiful visualizations of Aboriginal language networks: http://editingmodernism.ca/2014/06/visualizing-the-landscape-of-aboriginal-languages/

Kaarina Mikalson absorbs confidence from the community of DHSI, of EMiC, and of DH: http://editingmodernism.ca/2014/06/on-belonging/

Emily Ballantyne says goodbye to DHSI after 6 years: http://editingmodernism.ca/2014/06/saying-goodbye/

And so does Jeff Weingarten: http://editingmodernism.ca/2014/06/thoughts-on-the-last-dhsi/

Sarah Vela on her first DHSI, and the learning curve of DH: http://editingmodernism.ca/2014/06/dhsi-and-the-never-ending-learning-curve-of-the-digital-humanities/

Emily Robins Sharpe on the affective side of collaboration: http://editingmodernism.ca/2014/06/what-does-it-mean-to-collaborate/

Alana Fletcher demos out-of-the-box text analysis: http://editingmodernism.ca/2014/06/tool-tutorial-out-of-the-box-text-analysis/

Anouk Lang gives us eleven more reasons (on top of her original twenty-two) to go to DHSI: http://editingmodernism.ca/2014/06/thirty-three-ways-of-looking-at-a-dhsi-week/

June 13, 2014

“All the People”: A Look at Qualitative Research

“Meeting people, all the people, all the time” makes Anouk Lang’s list of “Thirty-three ways of Looking at a DHSI Week.” Similarly, DHSI is all about networks for Hannah McGregor. Reading through the many posts about DEMiC 2015, I am reminded about what I missed most about DHSI—the people. That’s right, I did not attend DHSI this year, but, in a fit of nostalgia, I am thinking about my past experiences. Last year, I wrote about the Digital Databases course. This year, I want to talk about what I left out: the qualitative research.

DHSI is, at least in part, about meeting people. Last year, I met “all the people,” which included two scholars who had worked on Carroll Aikins. As a bit of a recap, I am working on a critical edition of Aikins’s play “The God of Gods” (1919), which premiered in Birmingham, England, and involves Nietzschean intertexts, theosophy, an Aboriginal reserve, a loose adaptation of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, and anti-war sentiment, to name a few. DHSI brought me to Victoria, B.C. and to the stomping ground of James Hoffman (Thompson Rivers University) and Jerry Wasserman (University of British Columbia). Jerry offered to send me photographs of the first Birmingham production, which were waiting in my mailbox upon my return from the West Coast. James met with me several times to discuss his past research of Aikins, he lent me the manuscripts of Aikins’ unpublished plays, he shared theatre reviews of The God of Gods (some of which I had not yet uncovered!), and last but not least, he regaled me in stories about meeting Aikins’s family. Qualitative research, it seems, also played a major part in James’s work. I should probably mention that all of this wonderful research and sharing was unplanned: I met Jerry and James at separate talks, introduced myself and my work, and they offered the rest.

As if DHSI 2014 wasn’t already a gold mine of learning and of scholarly networks, it was also during a DEMiC social event that I connected with Melissa Dalgleish. As a result of that meeting, Melissa (who writes a series of posts about alt-ac work) is now working as a RA on the Aikins project (more about her RA work to come in a later post).

I can’t help but feel how indebted I am to qualitative research and to the generosity of scholars like Jerry, James, and Melissa as well as to networks of people like EMiC.

Figure 1Hart House Theatre: The God of Gods was performed at Hart House Theatre in 1922.

Qualitative research is important in the field of drama because the form relies on theatre reviewers or people’s personal notebooks to record production details. Do you engage with qualitative research in your work?

June 12, 2014

Re-envisioning Digital Heritage Management: “Mukurtu” and “Mukurtu Mobile”

This year at DHSI, I took the course titled “Cultural Codes and Protocols for Indigenous Digital Heritage Management”. This course utilized Mukurtu (pronounced mook-oo-too) CMS, an open source Drupal 7 platform for managing digital heritage, to explore the ways in which we can approach indigenous heritage materials (see http://www.mukurtu.org/).

Mukurtu allows for the marriage of traditional knowledge with data management, and its multi-authored commenting and free tagging capabilities promote an overall sense of polyvocality. Through its complex system of community-based permissions, the platform also communicates the webs of relations between places, ancestors, gender, and age, acknowledging the protocols imbued both within the community and those external to it. To determine the cultural protocols for a heritage item, one might consider the following: How do you want to share and manage access to this item? Who do you want to be able to view, add, or edit information? Is the content restricted to gender? Is the item sacred?

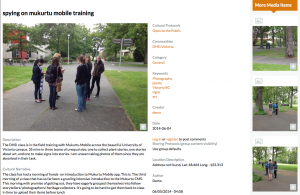

Our project for the week involved separating into three teams – Team Plants, Team Art, and Team Signs – and using the mobile app “Mukurtu Mobile” to incorporate fieldwork (photos taken around the UVic campus) into our demo sites. The app, while an excellent drain of my iPhone battery, allowed us to record information alongside each photo, and used geolocation to record our exact coordinates at the time each photo was taken. As a group, we needed to work together in order to determine the cultural protocols the applied to our content, in relation to possible viewing communities (our own team, DHSI, and UVic for example). We decided that some images should only be viewed by members of our group, Team Signs (strictest permissions), but that most images could be viewed by the DHSI/UVic communities (more public permissions).

Fig. 1 – Content generated by Mukurtu Mobile app and uploaded to Mukurtu site

When using this platform to manage heritage items in an indigenous community, the cultural protocols and sharing settings are extremely important. For example, certain heritage items may only be intended for males, specifically over the age of 18. Without these protocols in place within the Mukurtu system, anyone in the community would be able to view the items, creating an upset between traditional knowledge and the cultural codes put in place to govern it.

Our sample project was helpful, particularly for providing a hands-on experience navigating the Mukurtu interface; the project also sparked interesting discussions regarding permissions and protocols. Most importantly, this course forced me to consider the implications of my own research concerning West Coast First Nations literature. Through platforms like Mukurtu, it becomes possible to mediate the tension that has previously existed between technology and culture, and instead foster an environment focused on community-based heritage management.