Archives

Archive for February, 2011

February 17, 2011

How to Post a Blog to the EMiC Community

Have you been enjoying reading the EMiC Community blog? Do you want to post something of your own but are unsure of how to do so? This post will walk you step-by-step through the process of posting your first blog to the EMiC Community space.

When you visit any page on the EMiC Website, you’ll see a link to “Log in” at the top right of the page.

Click on this link you’ll be a taken to a page where you can enter your login details, which you will have received when you signed up as a member on the site. If you’ve forgotten your password, click on the “Lost your password?” link below the log in box.

Once you’re logged in, you’ll be taken to the user dashboard.

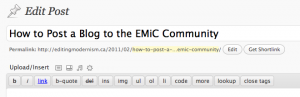

To post a blog entry, click on “New post” on the top right of your screen (or “Add new” under “Posts” on the left navigation bar). You’ll be redirected to the post entry page.

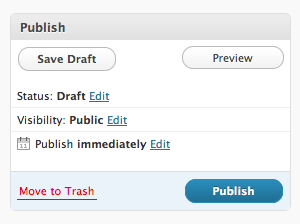

On the new post screen you’ll have the option (on the right) to choose to view a preview, save a draft, or publish your post. Your revision history will be listed at the bottom of the page. Your post won’t be visible on the public site until you click “Publish”.

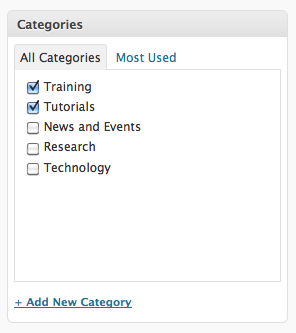

You will also have the option to create categories and tags for your post. You can choose to place your post in the following categories: Training, Tutorials, News and Events, Research, and/or Technology.

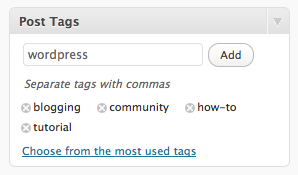

You may also wish to create tags (or keywords) for your post. You can do this in the “Post Tags” box.

When you preview or view a post, you might find that you need to return to the editing screen. Any time you want to get back to the WordPress Dashboard when you’re logged in, you can click the link at the top right of your screen.

It’s really as easy as that! We encourage all of our members to use the blog as a forum for public dissemination of knowledge about all EMiC-related research and training. Your blog posts are a crucial means of communicating with project participants, partners, and the general public. We want to hear from you!!

Still have questions? Email me at mbtimney@uvic.ca.

February 17, 2011

Editing Le Nigog, Part One: Planning a Digital Periodical Project

As we all know, the little magazine is a fundamental part of the production of modernist culture in Canada and across the globe. Various seminal texts, including Ken Norris’ The little magazine in Canada, 1925-80, Louis Dudek’s The Making of Modern Poetry in Canada and Dean Irvine’s Editing Modernity: women and little-magazine cultures in Canada, 1916-1956 have argued for the little magazine as the site at which multiple modernisms have emerged across Canada. While little magazine production is (arguably) at its highest in the 1940s and 50s, we are hoping to look backward, identifying for English audiences what could be the first French Canadian avant-garde periodical, Le Nigog, which ran for twelve issues in 1918. While this work is widely known in French Canadian circles, its place in English Canada is completely obscure.

For the last six months, EMiC Post-doctoral fellow Matt Huculak has been working on the early stages of the EMiC commons and co-operative spaces that he describes in an earlier post here. As a self-confessed luddite, I happily have enjoyed skirting the edges of this technology. While he has been working on the back end, I have been responsible for developing content for the site, so that it is immediately operational once the actual programming has been figured out. It is through this role that I began work on Le Nigog, and first began to explore the material reality of periodical preservation and began to actively cultivate its future as a digital edition.

This is the first of a number of posts that chart the progress of this project, beginning today with an examination of the project management side of DH work, focusing largely on hunting down information and allocating resources. Before the magazine hits the scanner, myself, as well as several new EMiC volunteers, Dancy, Katherine and Adrien, have been conducting detective work to 1) locate the magazine, 2) identify the contributors, and 3) begin the process of creating biographies and confirming copyright using death dates.

Le Nigog had only a limited circulation (approx 500 readers, according to Patricia Merivale), and therefore one of our most difficult tasks has been locating copies of the work in their original, unbound form. We are interested in preserving the complete texts, including advertisements. Since it was common practice to bind this type of text, the advertisement pages, which were on a different paper and numbered differently, were often torn out and not included in the final text. In order to fully socialize the text, it is integral to our project to include these advertisements as a part of the material condition of the magazine’s production.

I have only been able to locate nine copies of the magazine in libraries and archives across the country. Of those nine, only one complete, original set existed, and this copy was not available for viewing, except on-site in the archives. It definitely would not be available for a project of our kind. The copy we were able to procure was held privately, and while in excellent condition, we still currently only have the first ten issues. Numbers 11 and 12 remain elusive, and none of the libraries across the country have these two issues in their original form. So, the search for the actual magazine will continue on, though this is no longer our priority.

Using the issues we have, as well as a facsimile print edition of the text, I compiled a list of all the contributors, and then began the arduous task of tracking them down. With the copyright legislation in mind, I needed to determine which articles are now in the public domain, and which estates we would need permission from to reprint their work.

Because the periodical spanned literature, architecture, music and visual art, we have had to approach locating different contributors within their own discipline and its method of documenting its past. Starting with the literary biography, music encyclopedia, and history of Montréal architecture, we have begun to piece together the various lives of the contributors. Once we have been through these normal avenues, we have cast the net wider, and are now chasing down fragments, hunches, false leads and passing references to find the contributors and start their biographical sketches. Currently, of the thirty or so contributors, nine are in copyright. Three have no confirmed death dates, and continue to be on the run.

I am going to save copyright reflections for a later post. The last thing I want to talk about is our project management tools. To help the five of us share information, we have been highly dependent on one central spreadsheet. Early on, we decided that this document should be virtual, so that all information is shared to all participants and can be accessed from any location. We use google docs, and so far have been quite happy with that tool to span the whole project. We distribute tasks, track our hours and maintain a working bibliography all using these tools. That way, the moment one person discovers something, all records are updated. We have also started to download and save the documents onto our computers regularly as a form of additional backup. Once we start scanning and manipulating the images, they will have to be held in a central location with a backup until the co-op comes online. With the co-op we should be able to store images at various stages centrally, mimicking the research stage of our work while expanding its capacity and possibilities threefold.

February 15, 2011

Website Maintenance, 16 Feb. 2011, 7-9pm EST

The EMiC website will be undergoing some scheduled maintenance on 16 Feb. 2011 from 7-9pm EST. During that time you will be unable to access the site. Apologies in advance for the inconvenience.

February 9, 2011

Condiments and Canadian Literature: Origins of an EMiC Intern

In 1928, Dorothy Livesay exclaimed, “her mind was as keen as mustard” of Margaret Ford, a young teacher at Glen Mawr school in Toronto. It feels as though she could have written the same thing about me, working here at Dalhousie in 2011. Although it was surely intended as a compliment for Ford, I can’t help but carry the metaphor too far (as I always seem to do) when applying it to my own situation. Mustard may be keen, but the idea of enthusiasm, energy and interest also has implications by omission. No mention of vision or clarity, for instance. Mustard certainly isn’t clear. Though a fine condiment, mustard doesn’t work well on its own. It has a distinct colour and flavour, true, it’s bright, but not to the taste of all. Many would claim it’s positively repulsive. Some are allergic. And at only five calories a teaspoon, it doesn’t have much substance.

After spending a little quality time with the other blog posts, I am feeling especially mustard-like today. Perhaps it’s appropriate, then, that mustard is found in the form of a seed; a plant at the earliest stage of growth. It should also be noted that mustard is antibacterial, and very resilient. Not a bad place to start.

But I’m getting off track- let’s put the pungent mustard aside for a more academic flavour. The Editing Canadian Modernism seminar, where I first encountered Livesay’s name and poetry, transformed my education. Though I’d enjoyed each of my three years at Dalhousie with increasing intensity, my degree was ultimately inapplicable and unfocused. By the time I landed in Dean’s class I’d done a bit of everything: Renaissance and Medieval literature, American Gothic and African-American literature, Restoration Drama…the list went on. Until it hit Canadian literature, editing, or Modernism. That’s where it stopped. Psychologically scarred by the endless insipid required readings of Canadian authors trudged through in high school, I’d systematically avoided all courses with the name of my country attached to them. Conflating modernist writing with contemporary work (I know, forgive me), I had spurned the contemporary world as well. I inexplicably imagined it to be all glitter and fluff, something like the craft-time of literature. But Editing Canadian Modernism was the only seminar offered in the summer of 2010, and I’d heard many a friend scoff that courses were easier in the off-season. Obviously, these friends were not English majors. Even more obviously, they had never encountered the likes of an Editing Modernism seminar. The workload almost killed me, and I loved every minute of it. It was the most invigorating course I’ve taken at Dalhousie, and since then it’s been nothing but the modern and Canadian (before summer even came to a close I gobbled up a Canadian Literature course). Every essay I write tackles digitization, I fret about how faithful Kobo’s “The Sentimentalists” could be to Gaspereau’s, and even my parents know to link TEI tutorials to their emails if they actually want me to read them.

I started working with EMiC in September. At first I was content to chase down books or journals for scans and edits. But after a while, the fluctuating and occasional disputes (regarding contrast, discolouration, and the like) between the scanner and I became more than occasional. I began to spend my time hunting down publication information. Once January rolled around and my eyesight had deteriorated to around 20/40, I went back to give the scanner another chance. However, when I arrived to pick up the key, I learned that the entire room was closed off. The scanner appeared to have been slain by one of its very own. The special collections librarian informed me that the viewing window was twisted around completely while the camera lay on its side. I sent an email off to the EMiC office to notify them, and continued work on the spreadsheet. It wasn’t until our meeting two weeks later that the issue of the unworkable scanner was addressed. Any apparent horror accompanying the awareness that the downfall of a single piece of infrastructure had brought PhD, postdoctoral (and undergraduate) projects to a “grinding halt” was discussed with astonishing humour and composure. Technology fails. People fail. The important thing is that they don’t fail at the same time. Instantly the group began to spin ways around the problem, to continue their work, even to find great opportunity in the situation. I have never seen less of a “grinding halt” in my life, and this is precisely why I am confident that the Editing Modernism in Canada project will never fail.