Archives

Archive for the ‘Theory’ Category

April 14, 2015

Thinking Through Ethical Collaboration

I have been asked to reflect on my experiences as an EMiC funded RA. In this post, I think through my work with Canada and the Spanish Civil War (CSCW). My next post will look at my ongoing involvement with the critical edition of Dorothy Livesay’s Right Hand Left Hand. A big thank you to Emily Ballantyne for providing feedback on this piece.

By the time I joined CSCW, I had already worked for EMiC for a couple of years. I came into EMiC when it was already well underway. In many ways, I felt I could never really catch up; there were so many acronyms to learn, so many scholars to meet, and such a range of digital and literary projects that I only ever glimpsed. I learned many technical skills, but never enough to keep pace with this rapidly evolving and expanding project. I was impressed, excited, and ultimately (necessarily) overwhelmed.

But for me, the real beauty of EMiC is that it facilitated so many smaller projects. I got involved in Canada and the Spanish Civil War fairly early, and I witnessed its development. Emily Robins Sharpe and Bart Vautour study social justice movements, and they ensure that social justice is the foundation of their project. I am grateful to see the inner workings of the project, to see how policies and communities take shape around certain collective values. There is a great deal of emphasis in the digital humanities on skill development, and for a while I focused on developing my technical skill set. Through CSCW, I saw how deliberately I needed to develop interpersonal skills. It takes a great deal of space and energy to practice effective communication, transparency, collaboration and respect. I am grateful to have all of these modelled for me through this project.

In my own research, I ask what productive collective action looks like in Canadian fiction from the Great Depression. One chapter of my thesis looks at the Canadian Spanish Civil War novel This Time a Better Earth, and the different forms of antifascist work that it portrays. This project has asked a lot of challenging questions about what labour looks like, how we value different forms of labour, how women and people of colour become sidelined or exploited in collective work, why this happens, and how to model more sustainable and equitable movements. It is fairly easy to apply these critiques to literature of the 1930s, but much harder to critique and remake the projects, movements and institutions that I am a part of. This is time-consuming work, and it can be daunting. I am a privileged individual completing my second, well-funded degree in an increasingly neoliberal university system; I am already complicit in and benefiting from a broken system. But when I scale down, to the small-but–growing projects and communities I get to be a part of, I start to feel more hopeful and more prepared.

One of the reasons I am writing about the interpersonal outcomes of my RA work and not the digital outcomes is because all of that digital and editorial work feels incomplete, though I recognize the necessity of sharing ongoing work. But ultimately, I feel like those tangible things – the Canada and the Spanish Civil War website, the growing bibliography of Canadian writing on Spain, the forthcoming (and already underway) book series, even my own thesis – are not mine to claim. They are inherently collaborative, and as such their success hinges on healthy community. In an earlier EMiC post, Andrea Hasenbank wrote: “The work I have detailed here is one throughline of the work always being done by many, many people. You do not work alone, you should not work alone, and if you are not acknowledging those who work with you, your scholarship is unsustainable and unethical.” This, to me, is the real unfinished work that is giving me pause. How do I ensure that my work is always in line with my values? How do I respect my collaborators, academic and otherwise, my research subjects, my supporters, and my audience? I am grateful to EMiC and Canada and the Spanish Civil War for giving me the opportunity to apply these questions. In her farewell to EMiC, Hannah McGregor wrote, “communities preserve and support us; they give us perspective on what really matters, back us in our struggles, keep us sane and human in the face of systems that threaten to break us down.” Looking forward, I am confident in the excellent communities EMiC has produced, and in the productive and supportive thinking that it has fostered in so many of us.

October 24, 2014

Friday Roundup of DH Events & Deadlines

CSDH/SCHN Outstanding Achievement Award for Computing in the Arts and Humanities

Know a Canadian researcher or a researcher at a Canadian institution who has made a significant contribution, over an extended career, to computing in the arts and humanities? With your nomination, they could be receive the CSDH/SCHN Outstanding Achievement Award for Computing in the Arts and Humanities and be invited to address the society in a plenary session of the annual conference at Congress, which will be held in Ottawa in the spring of 2015.

For a list of previous recipients, see http://csdh-schn.org/activities-activites/outstanding-awards-prix/

Nominations of up to 500 words must be submitted by October 31, 2014. Only current members of CSDH/SCHN are eligible to submit nominations. Nominations must be sent by email to the chair of the CSDH/SCHN Awards Committee (dean.irvine@dal.ca).

IMAGINATIONS, 46th Annual Conference of the College English Association

The College English Association, a gathering of scholar-teachers in English studies, will have its annual conference in Indianapolis, Indiana, March 26-28, 2015.

The special panel chair for Digital Humanities welcomes proposals for papers and panels addressing the following topics:

- DH projects (digital collections/archives, digital editions, interactive maps, 3D models, etc.)

- DH research tools (text analysis, visualization, GIS mapping, etc.)

- DH pedagogy (teaching methodologies, curriculum development, project collaboration, etc.)

- DH centers (supporting research, consulting services, teaching faculty/students, etc.)

- Digital Project Management

- Data Curation

- The Future of DH

Please submit your paper title and abstract (200-500 words) to http://cea-web.org/ by 1 November 2014.

ELO Conference: The End(s) of Electronic Literature

(For anyone who happens to be in Norway August 5-7, 2015)

The 2015 Electronic Literature Organization conference and festival will take place in Bergen, Norway. This year’s theme encompasses the following topics: what comes after electronic literature, what purposes do works of electronic literature serve, international practices in electronic literature, electronic literature and other disciplines, and digital reading experiences made for children.

The deadline for submissions of research, workshop, and art proposals is December 15, 2014. More information can be found at http://conference.eliterature.org/.

July 22, 2014

Developing Productive Strategies For Collaborative Projects

On day 2 of the 2014 TEMiC Institute, Julia Polyck-O’neill presented on Susan Brown’s article “Don’t Mind the Gap: Evolving Digital Modes of Scholarly Production Across the Digital-Humanities Divide.” Following the presentation, our group discussed what Brown identifies as the dialectical relationship between the computer sciences and the humanities aspects of the digital-humanities. Having explored the dialectics of collaborative work in the “A Collaborative Approach to XSLT” course as part of DEMiC at DHSI, and previously blogged on the pedagogical nature of this type of work, I believe it to be useful to synthesize some of the ideas that surfaced during our talk.

Below are the core questions from this morning’s conversation:

1) How can a collaborative digital editorial project’s team, which consists of literary scholars and computer scientists, gain the most from this type of relationship?

2) In a project that includes members with different expertise and expectations, can/should hierarchical relationships be avoided?

3) Since every member contributes differently, how do we try to ensure the satisfaction of each team member?

Following our discussion, here is what I have learned, if not been reminded of: Dialectical work should be exactly what its name suggests, dialectical. That is to say, a project should not be dominated by any individual, but rather should encourage a team effort where alternative ideas and approaches are welcomed. I am not suggesting that designating a leader is an unproductive strategy, but that the leader, as a member of the group, should not be above the team. Instead, its members should recognize that everyone depends on each other for the success of the project, and should understand the potential value of varying perspectives and differing expertise. In addition, a team is a living organism, it should be willing to adapt, and should always remain dynamic. However, what must remain constant is that the many relationships within the team should always be mutually beneficial for each member; and, perhaps most importantly, credit ought to be given when it is deserved.

Although these core ideas might appear to be obvious, it is often easy (especially in the heat and chaos of editorial projects) to lose track of what makes the team aspect of these collaborative projects so useful. For this reason, I am thankful to be here at TEMiC where I am reminded of the importance of collaborative work, and how to efficiently maintain productive relationships.

June 13, 2014

“All the People”: A Look at Qualitative Research

“Meeting people, all the people, all the time” makes Anouk Lang’s list of “Thirty-three ways of Looking at a DHSI Week.” Similarly, DHSI is all about networks for Hannah McGregor. Reading through the many posts about DEMiC 2015, I am reminded about what I missed most about DHSI—the people. That’s right, I did not attend DHSI this year, but, in a fit of nostalgia, I am thinking about my past experiences. Last year, I wrote about the Digital Databases course. This year, I want to talk about what I left out: the qualitative research.

DHSI is, at least in part, about meeting people. Last year, I met “all the people,” which included two scholars who had worked on Carroll Aikins. As a bit of a recap, I am working on a critical edition of Aikins’s play “The God of Gods” (1919), which premiered in Birmingham, England, and involves Nietzschean intertexts, theosophy, an Aboriginal reserve, a loose adaptation of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, and anti-war sentiment, to name a few. DHSI brought me to Victoria, B.C. and to the stomping ground of James Hoffman (Thompson Rivers University) and Jerry Wasserman (University of British Columbia). Jerry offered to send me photographs of the first Birmingham production, which were waiting in my mailbox upon my return from the West Coast. James met with me several times to discuss his past research of Aikins, he lent me the manuscripts of Aikins’ unpublished plays, he shared theatre reviews of The God of Gods (some of which I had not yet uncovered!), and last but not least, he regaled me in stories about meeting Aikins’s family. Qualitative research, it seems, also played a major part in James’s work. I should probably mention that all of this wonderful research and sharing was unplanned: I met Jerry and James at separate talks, introduced myself and my work, and they offered the rest.

As if DHSI 2014 wasn’t already a gold mine of learning and of scholarly networks, it was also during a DEMiC social event that I connected with Melissa Dalgleish. As a result of that meeting, Melissa (who writes a series of posts about alt-ac work) is now working as a RA on the Aikins project (more about her RA work to come in a later post).

I can’t help but feel how indebted I am to qualitative research and to the generosity of scholars like Jerry, James, and Melissa as well as to networks of people like EMiC.

Figure 1Hart House Theatre: The God of Gods was performed at Hart House Theatre in 1922.

Qualitative research is important in the field of drama because the form relies on theatre reviewers or people’s personal notebooks to record production details. Do you engage with qualitative research in your work?

May 17, 2014

Tools from Post-Ac / Alt-Ac Careers: The Digital Engagement Framework

Since finishing my MA and deciding to pursue a career outside academia instead of a PhD, I have encountered plenty of discussions and discovered several resources that could fit just as well within academic projects in the humanities. As a Museum and Communications Coordinator for a non-profit heritage organization, issues surrounding collecting, archiving, and organizing information, cultural objects, and historical narratives are always present in my work. Many of these issues are related to how we can best engage an audience in these materials and narratives using digital platforms. This is the first of a few posts that I hope to write in order to share tools from my work outside academia that I feel would be useful to the EMiC community. Anyone else who has ideas and resources to share that bridge the divide between academia and post-ac / alt-ac careers should feel encouraged to do the same.

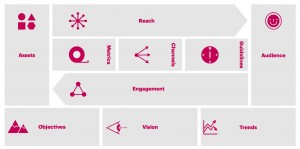

I attended two workshops at the Canadian Museums Association conference in Toronto this April, one of which was about incorporating digital strategies into project planning. The workshop was led by Jasper Visser, who travels the world to give talks on The Digital Engagement Framework. This framework is a tool that helps you decide which digital technologies will best achieve your goal and engage people in your project. The framework encourages users to map out who their audience is, what they can offer this audience, and what the audience can offer in return. The next steps involve planning how digital tools can be used to facilitate a mutually beneficial relationship between the project organizers and their audience. Visser has created an entire book on the topic that includes worksheets and case studies. It can be downloaded (along with the worksheet pictured above) from the digital engagement framework website.

I found the tool very useful for streamlining ideas about crowd-sourced projects that depend on audience contributions. Visser’s workshop asked participants to think past the initial engagement of an audience and also create a strategy that will retain an audience and cause an audience to be invested in a project. Since invested audiences need to feel that they are adding value to a project and that their efforts are recognized, the workshop included ample discussion on social media and how it can support crowd-sourced projects. The workshop also forced me to realize that, since only about 1 out of every 100 people remain interested in a project after initial engagement, targeting an audience 100 times the size of my ideal audience is a necessary first step in obtaining the participation levels I would like to achieve.

All in all, I think this resource is a useful tool for anyone planning a digital project that will use crowd-sourcing to obtain materials (such as an online edition that will ask for annotations from readers), for anyone who has a non-digital project that will require digital tools to engage with an audience (such as a textual edition that will be promoted through social media and other online platforms), or simply for anyone who has a project in mind and wants to take the first steps in considering how to get people interested in it– specifically in a world where digital interactions are not only the norm, but a necessity for generating a large and invested readership.

June 24, 2013

Hacking and Engineering: Notes from DHSI

A few weeks ago, at DHSI, I was giving a demo of a prototype I had built and talking to a class on versioning about TEI, standoff markup and the place of building in scholarship. Someone in the audience said I seemed to exhibit a kind of hacker ethos and asked what I thought about that idea. My on-the-spot answer dealt with standards and the solidity of TEI, but I thought I might use this space to take another approach to that question.

The “more hack less yack” line that runs through digital humanities discussions seems to often stand in for the perceived division between practice and theory, with those scholars who would have more of the latter arguing that DH doesn’t do cultural (among other forms of) criticism. That’s certainly a worthwhile discussion, but what of the division, among those who are making, between those who hack and those who do something else?

I take hacker to connote a kind of flexibility, especially in regards to tools and methods, coupled with a self-reliance that rejects larger, and potentially more stable, organizations. Zines. The command line. Looking over someone’s shoulder to steal a PIN. Knowing a hundred little tricks that can be put together in different ways. There’s also this little graphic that’s been going around recently (and a version that’s a bit more fun) that puts hacking skills in the context of subject expertise and stats knowledge. Here, what’s largely being talked about is the ability to munge some data together into the proper format or to maybe run a few lines of Python.

This kind of making might be contrasted with engineering—Claude Lévi-Strauss has already drawn the distinction between the bricoleur and the engineer, and I think it might roughly hold for the hacker as well. In short, the bricoleur works with what she has at hand, puts materials (and methods?) together in new ways. The engineer sees all (or more) possibilities and can work toward a more optimal solution.

Both the bricoleur and the engineer are present in digital humanities work. The pedagogical benefits of having to work with imperfect materials are cited, and many projects do tend to have the improvised quality of the bricoleur—or the hacker described above. But many other projects optimize. Standards like the TEI, I would argue, survey what is possible and then attempt to create an optimal solution. Similarly, applications and systems, once they reach a certain size, drive developers to ask not what do I know that might solve this problem but what exists that I could learn in order to best solve this problem.

My point here has little to do with either of these modes of building. It’s just that the term “hack” seems to get simplified sometimes in a way that might hide useful distinctions. Digital humanists do a lot of different things when they build, and the rhetorical pressure on building to this point seems to have perhaps shifted attention away from those differences. For scholars interested in the epistemological and pedagogical aspects of practice, I think these differences might be productive sites for future work.

April 26, 2012

Evaluating Digital Scholarship

Great news for EMiC scholars: The MLA has released its guidelines for evaluating digital scholarship. I encourage everyone to look through this important document as a way of thinking about your own projects. http://www.mla.org/guidelines_evaluation_digital. Does your individual project meet these basic guidelines? How can EMiC help you attain the goals set forth in this document?

In other news: in the next few weeks we’ll be launching a new “resources” page put together by Kaarina Mikalson. We’ll make sure these guidelines are a part of this new resource.

September 29, 2011

Are the Digital Humanities Relevant?

The question of the relevance of the digital humanities came up in my Digital Romanticism class with Michelle Levy at SFU, and I’m hoping EMICites will share thoughts, particularly as it pertains to our own work.

We were reading Matthew Kirschenbaum’s piece “What Is Digital Humanities and What’s It Doing in English Departments“, in which he defines DH via Wikipedia as “methodological by nature.” He continues by saying DH is “a common methodological outlook.”

A concern I raised is that, by focusing on its status as a methodology, we risk eliding the question of whether or not DH is actually a transformation of the humanities, not simply a way of doing the traditional humanities differently.

Are the end goals of DH the same as the end goals of the non-digital humanities? Or even: is DH a way of bringing a shared notion of ends back to the humanities, if we agree that this is something the humanities is missing?

My inclination is to say that DH is actually a transformation of the humanities, and one that we won’t fully understand for some years. There are two distinct paths I see now, and I would love to have a conversation about which one we want to go down (or whether, of course, there is some ‘middle way’).

One path sees DH fitting the humanities more neatly into a managerial paradigm. Because DH can more easily demonstrate that it requires and creates certain transferable, technical skill-sets, because of its work with quantitative indicators and data, etc. it is potentially more appealing to those who see a necessity for humanities work to produce those kinds of measurable outcomes.

This gets directly to the question that comes up almost every time we talk about where the humanities are going: are the humanities still relevant? I generally hear two types of answers to that question. The first is to submit to it completely, and argue that the humanities are relevant because of “critical thinking skills” that are essential in the workforce. This answer comes in the terms of managerial paradigm – I’ve heard the number of Globe and Mail journalists with English degrees cited as evidence of relevance here (and I have to say I question how good an indicator that is of the success of English programs).

The second type of answer to the question of relevance resists its terms entirely, and argues that it’s an unfair one, that it’s antithetical to the humanities to even think in those terms. This is basically the “education for education’s sake” argument.

What we discussed in class, and where I see a second path opening up, is that DH can give us a new outlook on relevance. Instead of submitting to the managerial paradigm entirely, or rejecting the question of relevance, what if we reframed the definition of relevance so that instead of meaning something like “having an effect on our value in a market economy” it meant something like “serving the public good” or even “serving the public good by refining our notion of what that means.”

In his article “Electronic Scholarly Editions” Kenneth Price tells us we should “celebrate this opportunity to democratize learning.” This is the second path opening up, one wherein DH transforms the humanities in ways that I think most DH scholars (certainly all EMICites I’ve talked with) embrace.

But sometimes (and I hope we can talk about this in future posts, and in the comments here) I think we too easily assume that DH will take this path by default. It likely won’t. If the second path is the one we want to take, we are being called upon now to be conscious of, and to clearly articulate, the ways in which our contributions democratize learning and serve the public good.

I’m really excited to hear what EMIC colleagues would say about this. How do these questions play out in your own scholarship and thinking? Have they shaped your involvement with DH or with EMIC, or even your plans for your own edition?