Archives

Author Archive

April 25, 2014

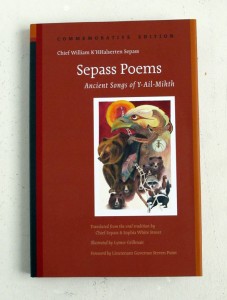

Returning Sepass Poems to their Oral Tradition

EMiC has funded a project to create an audio edition of Sepass Poems, and Ann Mohs of Longhouse Publishing has been overseeing the recording of the poems, which will be released later this year. The recordings are connected to a larger UBC initiative with which EMiC is affiliated. Ann has three books and 30 years of aboriginal connections informing her work on this project and she believes in producing high quality and meaningful publications. Below she gives an introduction to the project and her experience organizing it:

I have been given a very honourable place to be the publisher of the Sepass Poems, and recently to bring back the 16 Sepass Poems to their traditionally oral presentation—the way they were spoken back in William Sepass’ day (before 1943). This has been a joy, indeed.

Over the past year and a bit, an all-native talent cast has been recording in a small secluded studio in Burnaby for the production of the audio CD of the 16 Sepass Poems, Ancient songs of Y-Milhth. Longhouse Publishing has provided the direction and organization, and EMiC has generously provided the funds.

Longhouse Publishing gratefully took on the audio CD project as a natural extension of the book—a lovingly published 3rd edition sponsored by generous corporate funders with vested interests in things Aboriginal. After it caught the interest of Dr. Dean Irvine, and he brought up the query of the audio CD and the funds to achieve it, Longhouse Publishing moved quickly to make it happen in the right way. Thank you, Dean!

A little about the Poems: William Sepass recited these 16 poems from memory—training as orator from childhood—in the traditionally oral way. This set of 16 poems speaks of the beginning of the world, how everything came to be, and incorporates in story-form the physical, spiritual, and social attributes played out by humankind in its development along the way. In the oral tradition—unlike print—these stories take on an amazing dimension, and will delight all listeners. Traditionally and culturally, they were meant as teachings to be spoken and listened to!

I am so grateful for the contribution and opportunities EMiC has given Longhouse Publishing through Dr. Dean Irvine. He is the Sepass family’s Champion, and I know they, too, are grateful for the recognition of importance that Dean has placed on the Poems. Without this support, there would only be the desire to hear the poems in the oral tradition—not the opportunity to hear them!

April 17, 2014

TEMiC in Review: A “Smorgasbord” of Meaningful Discussions

Leading up to TEMiC 2014, I will be sharing some comments from last year’s participants. This week, Graham Jensen, PhD student at Dalhousie University, writes about his experience at last year’s TEMiC training event in Kelowna, BC:

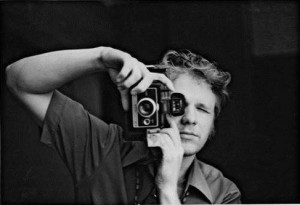

This past summer, I was fortunate to be one of the participants in EMiC’s summer institute (TEMiC) in beautiful British Columbia. The week-long course consisted of a series of lively seminars; afternoon workshops and presentations by a first-class line-up of artists and scholars; and both on- and off-campus readings by some of Canada’s most renowned or up-and-coming poets (imagine Erín Moure, Sonnet L’Abbé, Shannon Maguire, kevin mcpherson eckhoff, George Bowering, Frank Davey, Daphne Marlatt, Sharon Thesen, and Fred Wah gathered together in a single room). Against my better judgment, perhaps, I feel strangely compelled to use the word “smorgasbord” to describe TEMiC. But again, its great value consisted not only of the artistic, poetic, and scholarly delights it consistently placed on the proverbial table, but of the diverse artists, poets, students, and scholars it brought together around that table for meaningful discussions—of art, of Canadian poetry and poetics, and of editorial theory and practice in a wide variety of creative as well as critical contexts.

(UBC Okanagan Campus)

In partnership with EMiC, I am hoping to produce a digital edition of one of Louis Dudek’s long poems, and what I learned during, or in preparation for, my week in Kelowna will undoubtedly inform this project. In addition, my exposure at TEMiC to digital resources such as SpokenWeb has already begun to inform my own research and writing. I am extremely grateful to EMiC for its support, to the UBCO for being a gracious host, to the amazing speakers and poets who rained gold down on our heads every day, and to Karis Shearer and Dean Irvine for making the event possible in the first place.

(Louis Dudek)

April 3, 2014

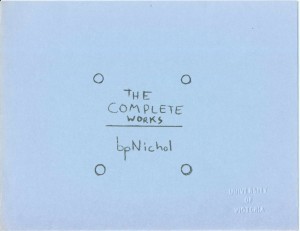

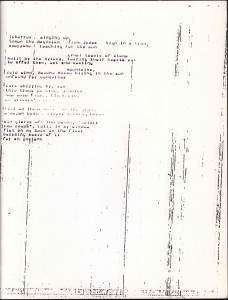

The bpNichol.ca Project: An Archive for Ephemera

*This post was written by Gregory Betts

In the avant-garde circuitry of Canadian small press publishing, the values of official verse culture are often inverted and reprogrammed. Whereas it seems natural in mainstream culture to value massive distribution, huge-scale production, and award-winning products, the authors who make the small press scene a coherent milieu are more likely to privilege precious objects that are individually made, circulated, and valued. This raises no problems for book reviewers or critics – they simply ignore what is sneeringly dismissed as “ephemera” – but it does raise an important problem for scholars of the avant-garde in the very limited access to primary materials. These items are often made in minuscule print-runs that quickly disappear into eccentrically organized private collections and only rarely get archived and made publicly available.

bpNichol is a definitive case of this type in Canada. On the one hand, his official verse culture position is convincing and significant: he published 24 books (depending on how you count them), many of which have been reprinted and remain in print, won the Governor-General’s Award, and has had the honour of an award and even a city road named after him. Two documentary films have been made of his work and influence, and a musical theatre interpretation of his collaborative sound poetry toured Canada in 2011. Outside of the spotlight, however, he also published thousands of “ephemeral” literary objects, including chapbooks, broadsides, comics, pillows, balloons, and much much more. Moreover, it is certainly the case that his ephemeral publications are more central to his poetics than his recognition within official verse culture. As the mark of an avant-garde reversal, his ephemera functions as a, if not the, central manifestation of his literary oeuvre.

The exquisite nature of the materiality of these textual objects presents a subsequent problem in attempting to address or consider the abundance of limited-run editions of his works. Reproductions or transcriptions come with the great loss of all the information encoded into the production choices made for his handmade works. How can one anthologize a two-page chapbook folded over in blue paper that sits small in the hand, for instance, or a single page with an enormous square cut out when the accompanying text of both refer to and depends upon those irreconcilable material features? As Lori Emerson and Darren Wershler write in their “Notes on the Poems” to The Alphabet Game: a bpNichol Reader, “Nichol’s print work demonstrates a particular and exacting commitment to the materiality of the printed page […] Attempting to fit such a heterogeneity into the framework of any book becomes what Nichol referred to in his own practice as translation. Translation never produces an exact equivalence” (318). For this reason, scholars of Nichol, and by extension of most avant-garde writers, must overcome the boundary of access to these rare and precious objects that evade the searching eye by nature.

What’s a poor scholar to do? Archives collect these objects, but struggle with the burden of locating and affording them. Scholars have to travel to incomplete archives, and are dependent on raising funds for that travelling to complete their work. In light of these fundamental problems, the digital facsimile reproduction represents an imperfect solution. They, too, are compromised translations of the work; no mere screen will replicate the strained feel of opening a staple-bound book. They do, however, present a unique opportunity for capturing the material presence of an avant-garde work. You can see the rust of the staples. You can see the inkmarks pressing through thin paper.

So just scan and dump them on the net? There are a number of digital archive models, and even a number of digital archive models for bpNichol’s work.

There is the PennSound archive that hosts .mp3 files of Nichol’s sound work and readings: http://www.writing.upenn.edu/pennsound/x/Nichol.php. These works are all presented with the permission of the Nichol estate, and are assembled haphazardly by the availability of recorded material and the willingness of volunteers to digitize and post work. Only limited information about the material is presented in the accompanying notes and descriptions.

There is the Ubu.com archive that presents scanned versions of complete texts: http://www.ubu.com/vp/bpNICHOL.html. These works are not presented with the permission of the Nichol estate; they are pirated editions. As with PennSound, they too are assembled haphazardly by the interests and availability of volunteers and come with even less information on each work.

Another model is provided by poet and publisher jwcurry with his Beepliographic Cyclopedia. While the Beepliography is primarily an offline project, curry uses digital facsimile to present individual Nichol textual objects as a Flickr photostream of (at present) 3, 477 photos: https://www.flickr.com/photos/48593922@N04/sets. Unlike the other two digital Nichol archives, the Beepligraphic Cyclopedia does not present entire works. Instead, each photo includes bibliographic information of a particular object and material evidence of its publication. Through this archive, you can learn about thousands of Nichol projects and to a certain degree see what each of them look like. It is uncertain whether these facsimiles are reproduced with the permission of the Nichol estate.

Beyond Nichol projects, American scholar and poet Johanna Drucker’s Artists Books Online presents a compelling example of a digital archive built around facsimile reproductions: http://www.artistsbooksonline.org/. Her model includes extensive notes about each entry, and full facsimiles of the works.

The bpNichol.ca digital archive portends to build from these models into a more comprehensive, more systemic record of works. With the permission and active support of the Nichol estate, the website aims to become the largest repository of complete works, photos, audio and video files on the internet. Even though the website is currently not available, previous incarnations of the website have already created an enormous database of digital facsimiles and documentary materials that await resurfacing. The ultimate ambition of the project, however optimistic that may be, is to create a complete digital set of Nichol works. The project will also include posthumous publications, previously unpublished works from the archives, and, eventually, critical responses to Nichol’s work.

Right now, the bpNichol.ca archive is not available. We are in the process of migrating to a newer version of the Drupal content management software – revealing a poignant hazard of digital life; the speed of anachronism in computers. As we update, we will be adding in new citations extensions that will allow us to capture historical information about the creation of a work and to associate multiple creative works with a single file, working under the assumption that most works contain a network of creative acts and incumbent copyrights. Reflecting the full nuance of digital publishing, we are working to allow artists (and rights holders) to better articulate their intentions for the creative use of their work.

Why is that a concern of the digital archive? Digital archives present copies of works in a way that is decidedly different from scholarly digital editions. Such projects work from primary materials and re-render original works through a systematic editorial process. A digital archive, in contrast, aims to facilitate editorial and pedagogical engagement with primary works. Eventually, scholarly digital editions might be developed, but that is not the current ambition of the website. Establishing and clarifying the copyright implications and boundaries of each work, however, will simplify the process for editors and scholars alike.

What’s next? After the current round of upgrades, the website will be relaunched hopefully in the Fall with significantly more works digitized, easier means of navigating the materials, and greater capabilities for scholars and general readers. We want people to be able to access Nichol’s ephemera while compromising the spirit of the original as little as possible. Ironically, though, the nature of the website is such that we will contradict the small press ethos by creating massive distribution and huge-scale production of Nichol’s work. In light of this contradiction, I take comfort from Nichol’s dictum that “language opens worlds, / little yields to unwilling readers” (“TTA 17”). Accordingly, everything on the website will be free, open, and awaiting your attention.

“everything at once

altogether

completely tangled together […]

everything at once

altogether & forgotten

completely remembered

thrown out” (“Extreme Positions” 4)

To commemorate the occasion of the website’s relaunch, on 7 November 2014, all of us associated with the project and many more will be gathering to celebrate what would have been Nichol’s 70th birthday at a one-day symposium at Brock University (in grateful affiliation with the EMiC project). The symposium will feature talks, small press workshops, roundtables, poetry readings, and more. Did somebody say Fraggle Rock dance your cares away party?

February 19, 2014

Call for Papers: Two Days of Canada Conference and bpNichol Symposium

THE 28TH ANNUAL

TWO DAYS OF CANADA CONFERENCE

FOLLOWED BY A

SPECIAL ONE-DAY SYMPOSIUM ON

BPNICHOL’S LIFE AND WORKS

5th-7th November 2014 “Avant Canada: Artists, Prophets, Revolutionaries”

Since the 1920s, when Canadian avant-gardist Bertram Brooker announced art’s imminent triumph over business, the discourse of avant-gardism in Canada has frequently combined revolution, aesthetics, and ecstatic projections of the future. The 28th annual “Two Days of Canada” conference at Brock University, the oldest Canadian Studies conference of its kind in Canada, invites scholars and graduate students in all disciplines who research any aspect of the Humanities or Social Sciences in the Canadian context to a conference centred broadly on the idea of what lies ahead for Canada and the arts in Canada.

This conference represents an opportunity to reflect on the state of the future in Canada as well as the role that forward thinking artists, philosophers, and revolutionaries have played and might yet play in shaping what lies ahead. Many possible topics comprise the broad theme of this conference, such as:

- dissent, disruption, and revolution: from early rights-based activisms to contemporary movements like Idle No More and Occupy

- future gardes in Canada and the future of the modernist avant-garde

- editing, publishing, and archiving the avant-garde

- teaching, mentoring, and inventing the avant-garde

- politics, political agency (especially including decolonization), and the arts

- equity, inclusiveness, and ideas/models of community

- movements, networks, nodes, and manifestations

- the impact of digital methodologies

- race, gender, and class in avant-garde production, dissemination, and recognition

- border crossing, transnationalism, and globalization

- futurist representations and the mediated future

- the theory of avant-gardism and modernism in Canada vis-à-vis international models

- the history, historiography, and boundaries of Canadian avant-gardism

Proposals for individual papers, presentations, or panels from all disciplines, covering any aspect of Canada’s future or the role of the avant-garde in Canada, are welcomed. Papers intended for the bpNichol symposium should be marked as such (see the next page). Abstracts should be no longer than 250 words and may be sent to Gregory Betts, Department of English Language & Literature (gbetts@brocku.ca) before 3 March 2014. Please attach a 50 word biography to your submission.

At the corner of mundane and sacred: A bpNichol Symposium

Friday 7 November 2014 9am – 9pm

This collaborative symposium of scholars, writers, visual artists, musicians, and those interested and invested represents a cogent network of energies focused on the award-winning work of Canadian poet bpNichol (1944-1988). Nichol was an enormously prominent literary figure, with substantial influence on small press and experimental writing communities in Canada, the United States, and beyond. He has been the subject of countless books and essays by writers in both countries, and is the subject of a current outpouring of academic interest that has given rise to the republication of many of his books.

This one-day symposium on Nichol’s life and works will be held at the Niagara Artists Centre in downtown St. Catharines, in collaboration with Brock University’s Centre for Canadian Studies and the Editing Modernism in Canada Project. It will include plenary speakers, roundtable discussions, special topics panels, workshops on avant-garde pedagogies and production, a poetry reading, and a Fraggle Rock-themed dance party. Papers exploring any aspect of Nichol’s production or the scholarship on Nichol are welcome. Proposals for individual papers, presentations, or panels are encouraged. Abstracts should be no longer than 250 words and may be sent to Gregory Betts, Department of English Language & Literature (gbetts@brocku.ca) before 3 March 2014. Please attach a 50-word biography to your submission.

January 10, 2014

What It Means to Annotate: Chris Ackerley talks text, context, and the universal library

This post is written by Chris Ackerley of the University of Otago.

Annotating Malcolm Lowry’s Swinging the Maelstrom

Lowry came to my attention, many moons ago, when I was doing my PhD at the University of Toronto. I was sitting, I recall, in the dining room of Hart House, solving the problems of the invisible universe, when somebody came along, and said: “You are working on Joyce. I think you’ll like this”; and left me a copy of Under the Volcano. He was right. I was. I did. I went home that evening and began to read. Some days later, having reached the end, I did what I only later appreciated the novel’s “trochal” structure required me to: I re-read chapter I, now as XIII, and before really being aware of doing so I was into my second (and richer) reading. This probably contributed to my liking of the story Lowry tells, of somebody who borrowed a copy of Ulysses and returned it the next day: “Yes. Thank you. Very good.”

When I came to the University of Otago (New Zealand) one of the first things I saw in the student ghetto was a run-down dwelling apparently held together by a large placard: “The Farolito”. This was a good sign. It transpired that one of my colleagues was also a fan of the novel, and had introduced UTV into the undergraduate syllabus (back in those days when undergrads read), leading to booming sales at the campus pub; we must have been one of the first places, outside Canada, to teach this text. And when my first sabbatical rolled around, not having a clue about what ‘research’ entailed (we were hired to teach in those days), I decided that Mexico would be a good place to visit (it was), and that UTV was a good excuse to go there (indeed). Fortunately, I went via Vancouver, where I visited the Lowry Special Collection at UBC, met Anne Yandle who immediately adopted me as one of her many Lowry proteges, and Bill New, who said that if I found anything interesting in Cuernavaca then how about sending it to Canadian Literature. And UBC Press held out a tantalising possibility of publication, if I could meet their standards….

And find interesting things I did, indeed. Reading the novel in the town in which it was set gave its events both an immediacy and an intimacy, and while I was conscious that much had changed I was smart enough, despite my naivety, to realise that more would do so if it were not recorded. And it was there, perhaps, that I first truly learned to appreciate the way that things in books are not simply things in books, but rather part of a complex life that, however fragmented and ravished by time, is in turn part of a greater process. I also began to collect, often haphazardly, some of the Lowry materials that would eventually end up on my Lowry web-site: http://www.otago.ac.nz/englishlinguistics/english/lowry/

More by instinct than intellect, I began to develop an annotative sense, one generated partly out of a love of general knowledge in turn provoked by stamp collecting (“philately will get you everywhere”), but equally out of the influential study by E.D. Hirsch, Jr., Validity in Interpretation (1967), which remains my bible to this day. Hirsch offers as his working assumption the hermeneutic principle that “each interpretive problem requires its own distinct context of relevant knowledge” (vii); this constitutes equally the foundation of my annotative practice, an axiom of validity in annotation. The pragmatic problem, then, is to determine in both principle and practice how an “interpretive problem” and its “distinct context of relevant knowledge” might be identified. Broadly, this entails accepting Hirsch’s definition of the goal of valid interpretation as consensus, the winning of firmly grounded agreement that one set of conclusions is more probable than others (ix). My additional argument would be that this scientific discipline leads to readings that are richer than those generated by the relativism and polysemy of many contemporary approaches, precisely because of the constraints exerted by the dynamics of text and context.

An example is in order (one plucked from Hugh Kenner, The Pound Era (1971]): the ‘Song’ from Shakespeare’s Cymbeline, with its ingenuous couplet:

“Golden lads and girls all must

As chimney-sweepers, come to dust.”

An annotation might assume as the ‘interpretive problem’ the image of ‘golden lads’, and postulate as constituting its distinct context of relevant knowledge such matters as: (i) the contrast of youth and age, (ii) the exploitation of children as chimney-sweeps, (iii) the pun on ‘come to dust’, (iv) the contrast of gold, that braves time, with dust, the wages of mortality, (v) the chill of closure created by the rhyme of ‘must’ and ‘dust’, (vi) the echo of Genesis 3.19: ‘for dust thou art, and unto dust shalt thou return’ and (vii) perhaps, the song as recycled in Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway and Beckett’s Happy Days. These details could be woven into an articulate cloak that accentuates the poignant contrast between rhythmical lightness and thematic gravitas. Such an annotation would be valid, but the interpretation ventured might be modified by new information (that is, by changes to the context of relevant knowledge). In The Pound Era (122), Hugh Kenner says ‘golden’ is a magical word that so irradiates the song that we barely consider how Shakespeare may have found it: “Yet a good guess at how he found it is feasible, for in the mid 20th century a visitor to Shakespeare’s Warwickshire met a countryman blowing the grey head off a dandelion: ‘We call these golden boys chimney-sweepers when they go to seed.’” And suddenly all is clear: dandelions that wilt in the heat of the sun and cannot endure the winter’s rages, now as an image both startlingly new yet reassuringly familiar: death as the blowing of a common flower. What is striking about this image (in my direct experience, and that of most of my students on whom I have tested it), is that something that earlier was not perceived (indeed, was earlier not perceptible) has been somehow precipitated into consciousness, so that the ‘meaning’ seems to have altered; an entity not ‘there’ on one reading is revealed as a presence, a given, on another, though the lines are unchanged. There would be general consensus, I imagine, that an interpretation that accounts for (that is, admits into the distinct context of relevant knowledge) the dandelion is likely to be better (that is, of greater explanatory power) than one that does not. My hope as an annotator is to enhance this kind of awareness.

The arena of annotation then, is broadly the no-man’s land between text and context. Annotation partakes of the editing process, in that its first principle must be the best possible text; and it partakes of critical evaluation, by determining the appropriate weighting of the factors that should or should not be taken into consideration. This is an impossible process. I recall vividly a moment that made me want to throw Under the Volcano into the barranca. I had not considered that there was anything to say about the moment in Chapter IV when Yvonne, trying to get Geoffrey out of Mexico, thinks about owning a farm with “cows and pigs and chickens”; but, much later, looking at Eugene O’Neill’s ‘Bound East for Cardiff’ I read about Yank, a dying sailor, who dreams of dry land, and of owning a farm of his own, with [yes] “cows and pigs and chickens”. Now, a rule of thumb by which I work in determining the presence of allusion is: one echo, so what; two echoes, perhaps coincidence; three, almost certainly evidence of intention. The O’Neill passage had about a dozen points of clear contact with the Lowry detail, but nobody (I was simply lucky) would recognise it as an allusion; and this brought about an existential crisis in my life as an annotator: for if this is an allusion, then what is not?

I found consolation in two unlikely places. Firstly, Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist, its description of the condition of the soul as approaching ever nearer but never reaching the Creator; then, this sentiment as transfigured at the end of Beckett’s Molloy, where Moran thinks of his bees, and the mystery of their dance (in 1948 a code uncracked), with rapture, with exaltation: “here is something I can study all my life, and never understand.” And there was another gradual intimation: a sense of something that Lowry shares with Borges, of the virtual presence of a Universal Library, Platonic in its nature, in which everything written by anyone, anywhere, is filed, with different degrees of accessibility and retrievability (hence Lowry’s notorious “borrowing”). I once thought, in the arrogance of the days when I knew the answers (now, I am increasingly [or should that be decreasingly??] uncertain of the questions), that this was a mere conceit; it now strikes me increasingly as a profound, if not truth, then at least persuasive hypothesis.

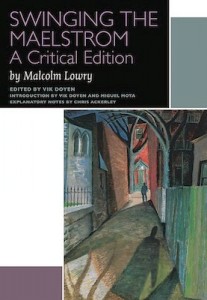

My annotations to Vik Doyen’s editing of Swinging the Maelstrom will not be definitive; they cannot be so. Yet both Vik and I would regard them as an intrinsic part of the process, as something occupying that middle ground between editing and interpretation, invoking the one to guide the other. As Vik has intimated, our work on this text goes back a long way: to the “Western Canadian Deans’ Short Course: The Malcolm Lowry Collection”, that he and I (quite frankly, more him than me, just like this book) taught together at UBC in 1987, where a virtual form of this edition was “taught” as a possible project; to the 1997 Lowry Symposium in Toronto, where the pledge to publish was renewed; to many pleasant hours in Leuven in 1998 with Vik (whose house was burgled the night after I left), and in Miami with Pat McCarthy, working over the text and annotations together; then to the 2009 symposium in Vancouver, which I attended with the sole ambition of eating blueberries in the heat o’ the sun, but came back as part of the EMiC team, committed to six further years of hard labour; and finally to working with the current team of international scholars on this project, and on the two to follow (I might add, parenthetically, that the 2,000 and more annotations to the forthcoming edition of Lowry’s In Ballast to the White Sea, occupying some 200 sensibly-spaced printed pages, represent the toughest challenge of this kind that I have ever faced; and one that would have been impossible—how on earth did I do those early volumes?—without the search engines of the Internet, itself perhaps the palpable manifestation in quotidian life of the Universal Library). T.S. Eliot famously likened the work of the individual writer or critic to that of one of the countless polyps that, working individually, yet make up collectively the greater reef; all I can add is that it has been a masochistic pleasure to have been one of these, and to see that a work that has been, one way or another, “in progress” for about twenty-six years now in the light of day.

December 13, 2013

Vik Doyen Shares his Journey to Genetic Criticism

(Post written by Vik Doyen)

Why does anyone start compiling a genetic critical edition of Swinging the Maelstrom?

The process behind this edition goes all the way back to the academic year 1970-71 when I was doing research on the Lowry manuscripts in the Special Collections Division of the University of British Columbia in Vancouver.

During my formation as an English major in Belgium I had been trained to focus on the final text of any literary work. My MA thesis on Under the Volcano was a typical example of this close-reading technique, in the tradition of New Criticism. My Ph.D. proposal — to apply the same technique to the rest of Lowry’s literary work — confronted me with a methodological problem: what about the posthumously published books? Could they be analysed in the same way as works that carry the seal of authorial approval?

The introduction to Hear Us O Lord From Heaven Thy Dwelling Place tells the reader that Lowry kept working on the stories during his final years in England and that the published text “contains Lowry’s final revisions, incorporated in the manuscript after his death by his widow, Margerie Bonner Lowry.”

For Lunar Caustic the situation seemed even more complicated. Conrad Knickerbocker’s Introduction to the Cape edition of the novella (London, 1968) is based on Margerie’s information:

“In England during his last years, Lowry had decided to do another draft of Lunar Caustic […]. At the time of his death he had reassembled and mixed the two drafts in the working method he always used. He often had five, ten or even twenty versions of a sentence, paragraph or chapter going at once. From these, he selected the best, blending, annealing and reworking again and again to obtain the highly charged, multi-levelled style that characterizes his best writing.”

Most reviews and critical studies of these posthumous publications treated them as if they represented Lowry’s finished texts. But for me, as a strong believer in authorial approval, there was no other solution than to have a close look at the Lowry manuscripts in Vancouver. My investigation of Lowry’s correspondence and the various drafts of his finished and unfinished works revealed that Margerie’s story about Lowry’s creativity during his final years in England was a fanciful reversal of the sad truth that, after two aversion treatments to overcome his lifelong alcoholism, the only manuscript he had touched in England was that of his unfinished novel October Ferry to Gabriola.

That confronted me with a double problem. First of all, I had to inform my Ph.D. adviser in Belgium about my conversion from a close reader of final texts to a genetic critic of unfinished projects. The second problem was that I needed Margerie ’s formal permission to quote from the unpublished materials. After my visit to her in Los Angeles in the summer of 1970 I received a written permission from her to quote in my doctoral dissertation “whatever you want”. But would that permission still hold for subsequent publications if my dissertation proved to be critical of her posthumous editions of Lowry’s work? When I asked her, during that visit, about Douglas Day’s long overdue biography of Malcolm Lowry, she firmly stated that there would be no Day biography of Malcolm Lowry. Perhaps Lowry’s official biographer had fallen out of grace after stating in his preface to Dark as the Grave that the stories of Hear Us O Lord were “collected (and in some instances completed) by Mrs. Lowry in the years after her husband’s death.”

In my doctoral dissertation, completed in 1973, I used a positive approach. Instead of focussing on what went wrong with the posthumous publications, I reconstructed the data of Lowry’s life from his own extensive correspondence and traced the gradual development of each story and novel from its earliest notebook entry to its latest available draft. That approach allowed me to deal with the posthumous publications as a kind of “Postscript”.

Because of academic and administrative responsibilities in the newly established American Studies Program of my university a new visit to the Lowry Collection in Vancouver had to wait until the Fall of 1984. I took advantage of that occasion to return to LA to discuss my research with Margerie Lowry, but her mental condition had made it impossible for her to deal with copyright matters. Via Betty Moss, a very helpful Lowry scholar and a confidant of Margerie’s, I received a recommendation from Margerie’s sister Priscilla to obtain copyright permission from Peter Matson, Lowry’s literary agent. That was a first step on the way towards a critical text edition.

A joint course with Chris Ackerley at UBC in 1987 led to the first idea of combining a critical edition of Swinging the Maelstrom with a set of annotations (vaguely comparable to Ackerley’s A Companion to Under the Volcano). By the time of the Lowry Symposium in Toronto in 1997 I had digitized the three versions of the novella and the editorial work could start. Chris completed a first draft of his Annotations by the late ’90s and followed it up with a number of revisions and additions.

The problem, however, was to find an academic publisher for this scholarly edition. That opportunity emerged after the 2009 Lowry Conference in Vancouver, when Paul Tiessen and Miguel Mota were able to get support from EMiC (Editing Modernism in Canada) for a three-volume Lowry project that would bring out critical editions of three unpublished works: Swinging the Maelstrom, In Ballast to the White Sea (edited by Patrick McCarthy) and The 1940 Under the Volcano (edited by Paul Tiessen and Miguel Mota). All three of them would be annotated by Chris Ackerley. And University of Ottawa Press would take care of the publication.

In his annotations Chris had repeatedly referred to the previous versions of Swinging the Maelstrom. The EMiC support made it possible to include in this scholarly edition not only the final version of the novella, but also the previous ones. This in turn allowed Miguel and myself in the Introduction to put special focus on the genesis of the novella. Paul and Pat situated this edition in the general context of Lowry’s work and, together with Chris, offered detailed critical comments. Miguel took care of all the contacts with EMiC and the Press and closely supervised each stage of the process.

Working together with this enthusiastic team was an enormous stimulus to do the fine-tuning of the manuscript and lead it through its final proofs. Many thanks to all of them.

November 28, 2013

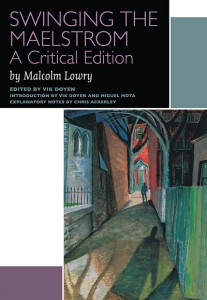

Critical Edition by EMiC Scholars Hits Shelves

A critical edition of Malcolm Lowry’s novella Swinging the Maelstrom is available now from the University of Ottawa Press, and three members of the EMiC community have their names on the cover and the fruits of their research within the pages.

The text was edited by EMiC collaborator Vik Doyen, who researched Lowry throughout his graduate degrees and did a genetic study of Lowry’s works for his dissertation. Doyen previously edited an edition of Lowry’s Lunar Caustic (an alternate name for Swinging the Maelstrom). EMiC co-applicant Miguel Mota has also edited an extensive list of Lowry works and joins Doyen as introduction co-author for Swinging the Maelstrom. Chris Ackerley, another EMiC collaborator and editor of Lunar Caustic, contributed the notes to the Maelstrom edition– an edition that lays out all versions of the text that exist under all of its various titles. EMiC scholars Paul Tiessen and Patrick A. McCarthy also contributed to this critical volume.

Read more about the edition, the author, and the editors (or purchase your copy!) here:

http://www.press.uottawa.ca/swinging-the-maelstrom.

November 17, 2013

Survey on student labour, training and collaboration in DH projects

The following letter is a message from graduate students at Simon Fraser University, asking for the EMiC community’s participation in a survey about student involvement in DH projects. A great opportunity for both students and faculty to share their experience with collaborative research, the survey closes in one week. Read below for more information:

Dear colleagues,

We are a group of graduate students from Simon Fraser University working on a collaborative essay under the supervision of Dr. Michelle Levy about the role of student labour, training and collaboration in Digital Humanities projects. To this end, we have constructed two surveys to gather anecdotal and quantitative evidence about student involvement.

There are two survey options, one for student researchers and one for grant-holding faculty researchers, which can be found below:

Students: Click here to take the student survey.

Faculty: Click here to take the faculty survey.

We welcome your participation, and invite you to circulate this survey widely amongst your students and colleagues. The survey will be available until 11:59 P.M. (PST) on Monday, November 25th, 2013.

A copy of the aggregated findings of this survey will be available to all participants.

Thanks and best,

Katrina Anderson, Lindsey Bannister, Janey Dodd, Deanna Fong and Lindsey Seatter

November 5, 2013

“The word Canada mean something like progressiveness!”: Digitally identifying Canada as a sign of modernity in Clarke’s Survivors (by Paul Barrett)

This post was written by Paul Barrett.

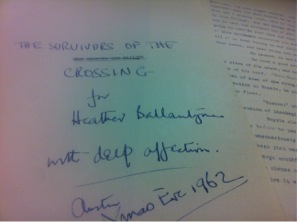

My project is a somewhat crazy attempt to locate Austin Clarke’s writing within the thematic and generic boundaries of Canadian modernism. Why crazy? Well, what does Clarke’s work – even his early writing – have to do with Canadian modernism? What generic and thematic connections are there between Canadian modernism and Clarke’s work? In addition to addressing these specific questions, I am also interested in why Clarke’s writing – particularly his early work – has been largely ignored by Canadian and Caribbean critics alike. My working thesis is that the untimeliness of these works – coming too late for modernism and too early to be qualified as ‘multicultural writing’ – the generic hybridity of Clarke’s early writing, and the transnational quality of these early works has baffled critics. I focus on Clarke’s first novel, The Survivors of the Crossing, a transnational Canadian novel concerned with questions of race and nation that was written throughout the 1950s and 1960s and published in 1964 (before Klinck’s Literary History of Canada!). The transnational bent of Clarke’s early novels, the focus on representations of race and racism in pre-multicultural Canada, and the formal qualities of Clarke’s work all made it difficult for Canadian critics in the 1960s and 70s to place Clarke’s writing within a familiar framework. Thus his early novels have received virtually no critical attention despite being notable commercial successes.

To attempt to understand this gap in Canadian scholarship I’m beginning with the provocative hypothesis that Survivors may be understood as an instance of late modernism in Canada. It is perhaps an instance of what Kronfeld calls “marginal modernisms” that lie beyond “the powerful cartographic paradigm: international modernism = Europe + United States” (4). However, the question remains: what aesthetic / formal / thematic elements in Clarke’s work might locate Survivors within Canadian modernism? And if the text can be identified as a form of late modernism, how might it redefine aspects of modernist Canadian fiction? Survivors begins with a letter from Canada to plantation workers in the Caribbean. The letter writer locates Canada at the center of global modernity, insisting that “Canada is a real first-class place!” and that “the word Canada mean something like progressiveness!” (9 – 10). The novel thus seems to invert colonial modernity by recasting Canada as a sign of modernity and contemporaneity and the British system of plantation labour as the relic of a less progressive era.

Movement is also a central theme of the novel as it is the movement of Caribbean people to Canada that leads the characters to see the plantation system anew. Clarke’s novel thus accords with Glenn Willmott’s argument that “The grounding of experience of modernity … in modern Canadian fiction is, therefore, not that of the dichotomy between or movement from the country to the town or city – the dichotomy of rural versus urban – but the deconstruction of that dichotomy or movement … the subtle ‘urbanization’ of the countryside itself” (152). In this case, however, it is the Caribbean countryside that is urbanized with Canada figured as a sign of global modernity. In what ways, then, does Clarke’s reimagining of Canada as a sign of modernity transform the manner in which he engages with the themes and motifs of Canadian modernism?

I am using topic modeling and Vocabulary Management Profiling software to try and answer these numerous questions. Topic modeling is a digital method of textual analysis that identifies recurring ‘topics’ or themes in a text and the relations between various topics within a single text or across multiple texts. I investigate the ways that topic modeling can help us understand the relationship between depictions of movement and space in Clarke’s novel. I am working in the William Ready Archives at McMaster University where Clarke’s archives (more than 22m of material!) are stored. I am also using Vocabulary Management Profiling software, which identifies marked shifts in an author’s use of language; I use this tool to assess the relationship between Clarke’s use of nation language and conventional English. I am particularly interested in tracing how Clarke’s use of nation language changes across drafts of the novel and may be affected by editorial intervention.

I’m still in the beginning stages of my project – scanning the multiple drafts of Clarke’s novel, converting the images into documents, and exploring the different methods for topic modeling. However, I hope that these methods will provide insight into the relationship between Clarke’s first novel and Canadian modernism and that Clarke’s work will provide a useful case study for understanding the implications of these digital methods of textual analysis.

October 8, 2013

Freeda Wilson Adds Another Dimension to Versioning Research

This post was collaboratively written by Freeda Wilson and Katherine Wooler

Freeda Wilson is currently completing an EMiC-funded project, which she anticipates will form part of her doctoral dissertation—supervised by Dr. Karis Shearer and Dr. Grisel Maria Garcia Pérez—to fulfill the requirements of her degree at UBC Okanagan. Her dissertation “Translating Bonheur d’occasion: Reinventing French-Canadian Culture in English, Spanish, and French” probes several editions and translations of Bonheur d’occasion [French 1945, 1947, 1947 (France), 1965, 1977, 1993, Spanish 1948, English 1947, 1980] and investigates variances between the texts, such as omissions and modifications. Freeda will determine the extent to which these variances affect the text, including aspects such as the representation of characters, religion, and culture. The main goal of her research is to examine the extent to which revision and translation affect the conceptual cohesion of the narrative of the 1945 edition of Bonheur d’occasion in the subsequent editions/translations. Furthermore, she will explore how digital humanities’ methodologies might compensate for conceptual variances between the original text and subsequent versions and translations, particularly in terms of the 1965 French edition, the Spanish translation, and the two English translations.

Freeda’s main challenge is how to best bridge the various editions in a manner which informs the reader but does not alter or take away from any of the individual editions. Another obstacle was copyright; however, she was fortunate to obtain permission from the Gabrielle Fonds to access and use materials for research purposes. While Freeda has experimented with Juxta (open source versioning/collation software), she will not be using it for her examination of variations of Bonheur d’occasion because uploading text to Juxta online would be a copyright infringement. Also, the software is not yet equipped to adequately support multiple languages.

Freeda found DHSI a very useful arena for generating ideas, especially since a major part of her process involves the digital/technical aspects of her project. Her project focuses on developing a 3D rendering of the variances in one chapter (Chapter XXX of the 1945 Pascal edition) across eight subsequent editions/translations of the text. This 3D visualization of Freeda’s research will present data on three axes simultaneously and coordinate which planes can be viewed at any given moment, revealing various sets of relationships depending on the view. The visible data and consequent themes will be determined by the researcher who is viewing the data. The different visual perspectives that are provided by this 3D model replicate how an object is viewed when held and rotated in the hand. Depending on the angle, various combinations of components will be visible at once.

Freeda is currently migrating the data from her research to her 3D model prototype in order to create the final 3D version, which in turn will integrate with its written counterpart in the dissertation. Her next step will be to create a website, which will house the various digital components relevant to her dissertation and to the various editions of Bonheur d’occasion, including the 3D model. These other digital components include timelines, charts, networks, frequency graphs, collation/versioning, data modeling/topic modeling, text manipulation tools, and multimedia materials. She is building the website herself, and her coursework at DHSI has significantly developed her vision. This portion of her work (the digitized components) will become available as she completes each item.