Archives

Archive for March, 2014

March 7, 2014

Draft 1, Draft ?, Draft ?: Editorial Notes and Nuisances

So, as some of you may know, for the past year and a half I have been working with Michael DiSanto on the George Whalley digital edition, the basis of which is a huge Whalley database. The first year was a serious learning journey filled with reading, training (DHSI!), planning, scanning, scanning, and more scanning, editing, uploading, describing, and transcribing. Now, the Whalley database has been migrated to a spiffy new website designed by Robin Isard, and we are really moving toward our digital edition. What I’ve been doing for the last several months is writing editorial notes for the poems we have selected as definite inclusions for the edition: “Elegy,” “Battle Pattern,” “Calligrapher,” “Pig,” “A Minor Poet is Visited by the Muse,” “Lazarus,” “Letter from Lagos,” and “Dionysiac.” Each note has ended up between 1500-3000 words, depending on how involved Whalley’s revision process was. Each one includes certain common elements: a description of the number of extant texts and their pages in manuscript and typescript, the publication history, a chronology of the versions, and any relevant biographical details (some of these are pretty fun, like the fact that “Pig” was inspired by a pig footstool Whalley bought in London).

Determining the chronology of documents has guided my writing of these notes, as I personally find the way the text has morphed from one version to the next over time to be the most important element of defining the revision process for a user. I begin by consulting the timeline of poems created for the project by “research assistant extraordinaire” Stacey Devlin, to make sure I don’t miss any documents corresponding to revision dates already identified, and then consulting the timeline of Whalley’s life to confirm where he was and what he was doing while writing the poem. Then I scour the database, checking in the relevant record container for all versions of the poem and using the search function to find related documents (pictures, audio recordings, etc). I jot down the titles of all the documents, with dates (if available), brief descriptions, and item numbers, and confirm that I’ve got all the dates recognized in the timeline covered (or make notes of which ones I’m missing!). Then the tough part starts—which version comes when? To start, I use the dated documents (there are always a couple of these, thanks to Whalley’s organizational foresight) to create a skeleton revision outline, then add tentative works to it based on their titles, placing together, for example, all the drafts titled “Resurrection Stone,” and all the ones titled “Lazarus.” When a document is untitled, we title it using the first line, so I can group these together too. Working with these smaller groupings, I then compare the works against one another line by line, making note of where handwritten revisions and marginal notes have been incorporated, where changes apparently not indicated by revision marks occur, and where one base text corresponds to another. I re-group, un-group, and group the versions again, and connect the groups to one another. This part of the process, where I compare different versions and note revisions, looks something like this:

As you can kind of see in the notes, the revisions I’ve recorded in the top draft are incorporated in a draft I’ve called “RS3” for short (“Resurrection Stone [3]”), and I’ve discerned that this draft is spread across multiple one-page records. I also use a whole slew of less technical aides, including the old post-it note page tracker, handwritten timelines, and the odd napkin collation (it’s the poor man’s Juxta!).

By the end, I’ve got a firm grasp of what I think the chronology is, and why, and can pinpoint particularly illuminating instances of revision for the reader of the editorial notes.

The images above are taken during my writing of the editorial note for “Lazarus,” which has been the most involved one yet (edit: not as involved as “Dionysiac,” which was printed in two separate versions and has only one real cross-over version!). I often feel very lucky to work on someone as organized as Whalley, who dates his drafts often and uses reasonably legible proofreading marks. One of the most confusing things about discerning the order in which various pieces and drafts of “Lazarus” were produced, though, is that Whalley seems to have flip-flopped a number of times on some things—on one draft he’ll change a certain word, phrase, or line break, and he’ll incorporate this change in the base text of another draft, and then in the next draft it’ll be back to the way it appeared before! One example of this is the way Whalley worked on the poem without, then with, then finally without its first stanza. A smaller and more tedious instance of this is his back-and-forth over what would become line 30 in the published poem, which appears as “He claws his way out of the undertow,” then “Out of this undertow he claws his way,” and back again, and back again, several times.

To be honest, I’m really enjoying writing these notes. I get unreasonably excited about discovering sources of Whalley’s inspiration, even if I can’t figure out how they’re being used—for example, there’s a marginal note on the very first draft of “Lazarus” that reads “See V. Woolf ‘On Not Knowing Greek.’” I took a fair stab at explaining this, but I’m still not totally sure what the connection is. A more obvious source of inspiration for “Lazarus” is the sculpture of that name by Jacob Epstein, the posture of which is the focus of Whalley’s early drafts of the poem.

This is probably quite an idiosyncratic “how-to” for editorial notes, but I hope it was illuminating in some way. I would welcome any tips and tricks from veteran editors on how to polish my approach!

March 6, 2014

Whalley Resartus

Thanks to Robin Isard, the eSystems Librarian at Algoma University, the Whalley website has a sharp new suit: http://georgewhalley.ca. Robin updated the site to Drupal 7 while making some significant upgrades to the database that sits behind the public side of the project.

Taken from a newspaper clipping in the George Whalley Fonds in Queen’s University Archives. The full image is on the home page of the new website.

A conference honouring Whalley on the weekend of 25 July 2015 – that date being the centenary of his birth – is in the works. It will be hosted by Queen’s University, his academic home from 1950 to 1980.

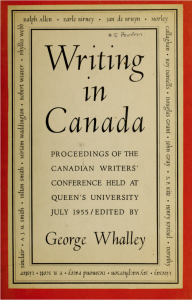

The plan for the last day of the weekend is to revisit the Canadian Writers’ Conference, which was held at Queen’s University from the 25th to the 28th of July, 1955. It is fitting to celebrate Whalley’s centenary and the sixtieth anniversary of the writers’ conference together because Whalley was one of the organizers and edited the proceedings, Writing in Canada (1956). The list of those in attendance reads like a who’s who of Canadian writers of the period: A.J.M. Smith, F.R. Scott, Morley Callaghan, Phyllis Webb, Miriam Waddington, and Dorothy Livesay, among many others.

More news will follow soon, I hope.

March 4, 2014

The Digital Page: Brazilian Journal

I began working with the Brazilian Journal four years ago, when Suzanne Bailey was working on a print-based critical edition of the text for Porcupine’s Quill. Brazilian Journal began as a diary kept by Canadian poet P.K. Page, from 1957-59, while she accompanied her husband to Brazil, where he was serving as Canada’s ambassador. When Suzanne and I began working on the text we were under the assumption that the only existing manuscript was Page’s original diary pages, now stored at the LAC. This situation simplified the editorial task, as we chose the first print edition of the text, published by Lester & Orpen Dennys on June 27, 1987, as our copytext.

Shortly before our new edition went to print, however, we discovered eight heavily annotated typescripts of the Brazilian Journal that showed a very clear evolution of the text from Page’s diary in the late 1950s to the polished text published in 1987. While vastly informative for literary critics studying both the text and Page’s work as a whole, these typescripts presented us with thousands of pages of new material. There was no easy way to present this genesis of the text, with its thousands of variants, in a print edition, and still have it be usable as a clear reading text. Zailig Pollock, as editor of the Collected Works of P.K. Page Project is attempting to create digital editions that do both. His solution is to create two separate, but related, publications: a printed edition, and an online database. The print editions, published by Porcupine’s Quill, are intended for general readers and students, rather than as primary scholarly resources. The online database, however, will display digital facsimiles of every version of the work—both manuscripts and published. The Brazilian Journal was chosen as the first of Page’s texts to undergo this two-pronged approach to a scholarly edition, and we finally have a working prototype of the digital database—what Zailig calls the Digital Page—to share with the wider EMiC community.

The digital database had to meet several requirements. First, it had to display a facsimile of each manuscript page. Second, it had to provide a clear narrative outlining the genesis of each manuscript page, placing all the changes and corrections in chronological order. Third, it had to present a clean reading text. The current prototype does all three of these things. Zailig has written a very useful guide to navigating the database’s interface [click here to read guide].

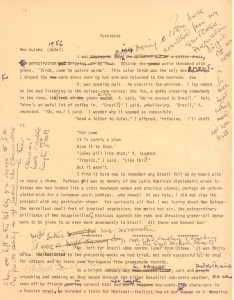

I thought it would be interesting to quickly show some of the work that went into building this prototype. Thanks to the help of some excellent RAs, we began by scanning all of the eight typescripts at a high-resolution to ensure that they would be readable online. (Each typescript is over 300 pages, so this was not a quick task.) After we had each typescript scanned, we began transcribing each page. We used OCR to help when we could, but often Page’s corrections and marginalia made this impossible. This is the first page of the first manuscript. While it is more heavily marked up than the average page, it does show what we were working with. We have identified five unique “editing sessions” on this page alone.

A session or ‘campaign’ as it is sometimes called represents a self-contained set of revisions. That is, all the revisions identified as being from a single session follow all of the revisions from earlier sessions and precede all of the revisions in following sessions. Within a session the chronological relationship amongst various sets of revisions is usually not obvious. There is no reason, for example to assume that revisions made on the first page precede ones on the last page. In contrast a revision in Session A to the past page of the document will precede all revisions in Session B, including those on the first page. The teasing out of the different sessions is base partly on writing material—pencil or ink of various colours or felt pen, in the case of Brazilian Journal—but other internal, and external evidence can come into play. The digital edition will include a discussion of the sessions and our determination of them.

We have identified six different sessions in the first manuscript. The five shown on the first page are:

A – typescript

B – felt pen

C – blue ink

D – pencil

E – black ink

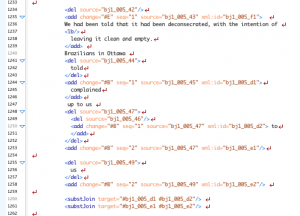

After transcribing each page, we had to code each page using TEI markup. Zailig developed a very specific set of tags, all of which are TEI compliant, to mark all variants in the text. Alongside this tag-set, we also tagged each “revision site” to its corresponding location on the manuscript page. By doing this, we have linked all revisions in the transcription with the manuscript page itself. This ensures that it is very easy for a reader to understand where a change takes place. (If you look at the prototype, you can see this linking in practice.) A sample of our coding for this first page looks like this:

After coding each page, we run the XML file through an XSLT program designed by Zailig’s son Josh, which outputs the HTML that you can see in the prototype. (If you are interested in learning about XSLT, you should check out the EMiC-sponsored DHSI course being taught this year by Zailig and Josh—“A Collaborative Approach to XSLT.”)

This is a lengthy-process, with the coding of each page taking at least thirty minutes—a page like the one above takes much more. As a result, it will take years to finish this project. But we are aware of this limitation, and have designed the digital database to accommodate this. We currently envision the Digital Page website to post new material as it becomes available. Thus, we will post the scans of each manuscript first. Then we will post the transcriptions, and finally, the coded pages. This will allow scholars to have access to the material before the digital edition is complete.

The prototype is still being in its beta phase. Zailig and I are constantly tweaking the coding when we encounter new problems that we need to solve. Josh is constantly adjusting the XSLT to ensure that the resulting HTML performs as it should. There are two limitations to the interface as it currently stands which we will be working on in future. The first is that currently the user can only move from any revision in the typescript to the image. Josh is currently writing code that will allow the user to move in the other direction, from any revision point in the image to the equivalent point in the transcription. The user will also be able to see at a glance the sequence of the revisions through the various, colour-code sessions. The next step, which is farther down the road, but which does not seem to present any insuperable difficulties, is to allow the user to follow the genesis through all of the relevant documents

If you have any comments or suggestions on our prototype, we would welcome them!

March 3, 2014

Reading of the Stage Adaptation of Ernest Buckler’s The Mountain and the Valley at Dalhousie University

Dalhousie University’s Theatre and

English Departments

present a reading of the stage adaptation of

Ernest Buckler’s classic novel

The Mountain and The Valley

by Nova Scotia playwright and

Governor General’s Award winner,

Catherine Banks.

The reading will take place on March 18th 2014,

7:30-10pm in the MacAloney Room,

4th floor of the Dalhousie Arts Centre.

After the reading there will be a brief discussion

with Ms Banks on the adaptation process.