Archives

Archive for June, 2011

June 29, 2011

Measure and Excess

Please find below a call for submissions for next year’s issue of the journal TransCanadiana on the EMiC. The call is available on the website of the Polish Association for Canadian Studies: http://www.ptbk.org.pl/Aktualnosci,5.html. Deadline for abstracts: 15 November 2011. Submission of articles: 31 December 2011.

June 27, 2011

Diginitiation

Yes you guessed it. This was my first year of workshops. I probably looked like my twelve- year-old self who arrived in Canada in 1998, two weeks into the start of a school year, spoke no English, and wore funny clothes: lost. You know that feeling like you’re watching a foreign movie with no subtitles? That’s how I felt in 1998, and that how I felt again when I first started the fundamentals workshop this year. But the similarity between this foreign experience and that other earlier one soon faded, as (to stick to my movie analogy) the cast and crew of DHSI and EMiC all stepped out of the screen and gave me a big digital/human hug. It was just code; nothing to be scared of.

I’m like you. Writing codes and learning entire languages to represent, analyze, and access information is not what I do on a daily basis. Not yet anyway, though, I have to say after my experience at this camp I’m not at all opposed to the idea. In my real life now I read books, I write papers (or poems), I bake bread, I blog, bike, and water my herbs. The reason I ended up in this amazing program was mainly my thesis adviser’s affiliation and involvement with EMiC, but I have to say, since I came back I have a wonderful feeling like I’m in on an awesome secret.

The secret is that the humanities and the digital world can be friends. That means my Dad (the software engineer) and I (the poet) are closer than we think. It means when my cyber-savvy younger sister says Twitter, my brain doesn’t have to auto-correct it to Twain. When you reduce the units of our currency to layers of ideas, lines, words, and characters, it all begins to come together. The most pleasurable part of the experience for me has been the realization that what I have started to learn systematically, has been practically in my life all along. I was already analyzing trends in literature, I was already blogging and tweeting and networking. Only now I have a really neat way of understanding the complex and exciting ways in which the information that goes through my life is connected to the processes that help it move along effectively. I can only hope to have a hand in these processes soon. A few more workshops and I don’t see what not.

June 22, 2011

Canadian Studies, Canadian Stories: Interdisciplinary Perspectives and Pedagogies

25th Annual Two Days of Canada Conference

Canadian Studies, Canadian Stories:

Interdisciplinary Perspectives and Pedagogies

Brock University, St. Catharines, Ontario

November 3&4, 2011

CALL FOR PAPERS

Currently celebrating its twenty-fifth year, the Two Days of Canada conference is one of Canada’s outstanding gatherings of scholars and students sharing interdisciplinary perspectives on the study of Canada. Each year, academic researchers, graduate students, undergraduates, and community members representing a wide range of disciplines and interests meet to share knowledge and expertise about matters of importance to Canadians. We are marking the 25th anniversary with a call for papers on the state of Canadian perspectives and Canadian scholarship within and beyond Canadian Studies. The theme for Two Days of Canada 2011 is ‘Canadian Studies, Canadian Stories: Interdisciplinary Perspectives and Pedagogies.’ The conference will be held at Brock University, St. Catharines, Ontario, on November 3&4, 2011.

The Two Days of Canada conference invites papers reflecting current research and thinking on ‘Canadian Studies, Canadian Stories.’ Possible topics include but are not limited to:

• Canadian Studies in universities and colleges; changes and challenges

• Pedagogy and practice in Canadian Studies

• Canadianists and Canadian perspectives in the traditional disciplines

• Interdisciplinary scholarship and research in Canadian Studies; theory and method

• Indigenous Studies and Canadian Studies

• Diversifying Canadian Studies; multiculturalism, post-colonialism and globalization

• Canadian Cultural Studies; beyond cultural nationalism

• Place and space; geographies of Canadian Studies

• Canada and Quebec; comparative perspectives in Canadian Studies

• Local sites and stories in Canadian Studies

• Origins and histories of Canadian Studies

• Canadian Studies in the international context

• Narratives of nation and locations of Canadian identity

• Canada and the US; the binational relationship in Canadian Studies

• Canadian Studies in the community; citizenship, engagement and participation

• The future of Canadian Studies; interdisciplinary, multidisciplinary or transdisciplinary?

Please send a 150 word proposal and a one page CV to:

Dr. Marian Bredin, mbredin@brocku.ca

Centre for Canadian Studies, Brock University,

500 Glenridge Ave., St. Catharines, ON L2S 3A1.

All submissions must be received by August 19, 2011.

June 18, 2011

Embarking on Love: Producing a Digital Edition of “I want to tell you love”

My recent participation at DHSI and DEMiC was not only preparation for my upcoming MA studies, but an attempt to throw myself into a group of interested scholars, programmers, humanists and other like-minded individuals. I attended the week’s events as part of the EMiC project and I am entirely grateful that the EMiCites have taken me into their fold. Together we shared an extraordinary week of intensive learning and community building.

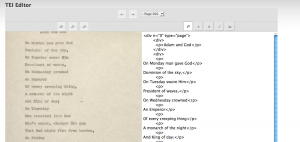

The focus of my academic work rests on an unpublished manuscript by bill bissett and Milton Acorn entitled I want to tell you love. The aim is to analyze and eventually produce a digital scholarly edition of the text. DHSI was the perfect place for me to begin collecting the tools and skills I need to complete the task. I enrolled in “TEI Fundamentals and their Application” which was taught by Julia Flanders, Doug Knox, and Melanie Chernyk. They were a dream to learn from. Flanders et al. taught clearly and overall the course was fun and informative. The trio made it easy for me to connect to a field with which I had no previous knowledge. Kudos to them! After the first day, my thinking of text and reading had completely changed. Not only am I now thinking about these ideas in a traditional analytical sense, but now I am considering how these ideas can be connected and then translated into a digital environment.

Admittedly, the first couple days of TEI were frustrating. This isn’t because its an incredibly difficult language to learn. It is because in the beginning stages you can’t see what you’re working towards. For a beginner like me, I had no idea what my mark-up might look like by the end. As I’m working I want to be able to ensure that I want to tell you love, as an edition, will be as aesthetically appealing as it is intellectually appealing. In order to see the end product of your encoding the text has to go through several other layers, layers which were not really addressed in our week’s agenda. A brief tutorial in CSS basics alleviated some of this anxiety, but I still possess a knowledge gap. Of course I realize that one week to learn TEI is probably not enough, other courses and more advanced learning is required. This is a responsibility I will own up to. I’m not disappointed to say that I’ll probably have to return to DHSI to build on and complete the skill set I desire.

The benefits of the TEI course do trump the drawbacks. On the other side, TEI is incredibly useful because of its ability to digitally connect interesting points, names, dates, themes, idiosyncrasies and other important pieces of information. This will be especially useful to my own project. For example, I want to tell you love is arguably a witness to the early stages of bissett’s unique orthography (an aspect of bissett’s poetry that has been of particular interest to bissett scholars for decades). One of the arguments I have developed from this point is that the manuscript marks bissett’s transition from Modernist modes of writing to Post-Modernist. His movement from a more conventional orthography to a personal, phonetic orthography is an evidence of this transition. TEI will allow me to track and take note of this transition as it occurs in the manuscript. In addition, TEI is not only a way of rendering data in a new, relevant format, but it frees the data to newer forms of analyses which consequently can open new doors for scholarship. TEI’s potential to develop new scholarship is especially important when addressing someone like Milton Acorn, co-author of I want to tell you love, whose legacy is sadly receiving less and less attention. It was at this moment of realization that EMiC’s mandate became clear. TEI and other digital tools can work to revive interest in Modernists and their writing. That’s incredible, yes?

All in all, DEMiC was a tremendous experience. The tools and skills I gained are invaluable. They will be built upon and put to good use.

June 13, 2011

The Agony and the Ecstasy of XSMLT

This year I took the workshop on XSMLT. It was probably the most useful of the three workshops which I have so far taken at DHSI but by far the most frustrating — one might almost say agonizing. Since returning from DHSI I have been generating, through XSLT, exactly the HTML files based on TEI-conformant transcriptions of some very complicated revised manuscripts. Though I am sure my coding will increase in efficiency and elegance as time passes, I really am fully confident for the first time that I have exactly what I need for my project — and that I have the wherewithal to explain my needs to the research assistants who will be encoding texts for me. I therefore would strongly urge anyone who is going to be involved in digital editing to take this course — even if they entirely lack a programming background, which I do . You may end up hiring someone to design your XSLT stylesheets, but even so, it is very important that you have some sense of exactly what it is you want them to do.

The experience, however, was definitely not fun. In fact, you might characterize it at times (and with a bit of exaggeration) as agony. This had nothing to do with how the course was actually designed and taught. What it did have to with was the fact that people taking the course came from very different backgrounds, with varying degrees of programming skills. As one of the least skilful people in the course, I found the going very rough. I have written a detailed assessment of the workshop from this point of view for its two instructors, Martin Holmes and Syd Bauman — who did an absolutely first-rate job — and I hope that some of my comments might help future instructors make the workshop less stressful and more appealing to people without backgrounds and programming — but I thought it might be a good idea, in any case, to share my experiences with other EMICites. My aim is both to encourage people to take the course, and to give them some sense of its challenges and how they might prepare for them.

The workshop was billed as being about XSLT, but in fact, virtually all of it was about XPath, for reasons I will explain in a moment. An XSLT file instructs your computer to go to a particular point in your XML file and to do something to it. I use XSLT exclusively for presentation purposes. That is, I may want it to present revisions in a certain colour, to centre headings, to indent the final couplet of a sonnet, or whatever. To do this you need to put directions in your XSLT file so that it will know where to go on the XML “tree” to find the part of the file you want it to transform. XPath is the language you used to do this, using terms like siblings, descendants, ancestors, parents, etc., informing you how to get where you want to go. I had no problem with the principles of XPath which are very simple, but I don’t think like a programmer (and I have a terrible sense of direction, which didn’t help) so I quickly found myself getting lost in the maze of any but the simplest XPath paths. I simply did not have the time to absorb and retain all the details of XPath syntax, even though I worked away in my room like a demon after classes, making this the least sociable DHSI I have attended. The difficulties were all the greater because by the end of the week Syd and Martin — and a number of the more advanced students in the class — were performing all kinds of magic tricks with their documents, which seemed to me totally irrelevant to anything I would ever want to do with mine.

What made the workshop extremely useful though, was 1) the very lucid account we were given of the basic principles of XSMLT/XPath and 2) the very very valuable hands on help I got from both instructors, not only with details of XPath that I had failed to grasp in class, but also with my attempts to work with a TEI text I had prepared in anticipation of the workshop. After talking to the two of them about these matters, I was encouraged that two of the most knowledgeable experts on TEI thought my approach to encoding my project, though not particularly sophisticated, was fully adequate to my needs and perfectly kosher TEI, without any need for “tag-abuse” or re-configuring the TEI schemata for my own purposes. Syd suggested a somewhat different kind of approach which would be somewhat more flexible but considerably more complex, and we agreed to continue discussions about it. But I was left with a strong sense that the choices that I had made early on in my project were reasonable and justifiable. By the end of the course I had accomplished what I had hoped for and I was kind of ecstatic.

What could have been done to make the experience of this workshop less frustrating, though? I would make the following suggestions:

1. If you happen to be one of those rare but not quite extinct DHSI birds who uses a PC, practice on a Mac before you start your class. I know this sounds trivial, but I wasted a huge amount of my time, as well as the time of my fellow students and my instructors, trying to figure out how to find my way around the Mac.

2. We used Oxygen for editing our files. Oxygen is a wonderful program and very easy to use. But you still need to learn how to use it. The instructors provided good instructions, in the course material and in their presentations, but with so much else to absorb I kept getting snarled up in technicalities until well into the 3rd day. Another enormous source of frustration.

3. Do some preparatory work before the workshop. Syd and Martin provided useful slides but they would have been vastly more useful if I had had access to them before the class. I suggested to them that they send a list of materials online, as well as of books, to all of the students enrolled in the course a few weeks ahead of time. With some of this behind you, you will be able to take full advantage of the many examples, exercises, quizzes, and discussions of basic principles that went on all week and which were received with great enthusiasm for those who were prepared, by their past experience, to fully appreciate them.

If this course is offered again, I think I may take it. With more experience I am sure I will have a much better time and learn a lot of things that were over my head this time around. — and I fully expect the ratio of agony to ecstasy to shift in my favour.

June 13, 2011

Just call me the Golden Gate…

This June marked my third time attending the DHSI (aka DEMiC) since I became a graduate fellow. My how we have grown! We may not fit on the Smuggler’s Cove balcony without violating fire safety regulations, but Victoria is starting to feel like a home away from home one week a year.

The strong sense of community generated by EMiC was enhanced this year by the Digital Editions course, run by Meagan Timney and Matt Bouchard. Instead of reflecting directly on this course, however, and all I learned from it (which was a LOT), I’m going to use this forum to share a few thoughts on the digital humanities in general.

I still recall the heady feeling of euphoria that filled me at my first DHSI. There is something utopian about the digital humanities, a foward-looking approach that makes the future seem bright and shiny no matter how fraught the present moment might be. Digital humanists seem to always have their eyes on the innovative interdisciplinary transnational horizon.

A few things have happened since that first year to temper that euphoria, however. I have experienced the gap between the ideal and the real when struggling to work with exciting visualization tools that have no instructions. I’ve realized how hard it is going to be for the academy to go digital when trying to encourage busy academics to contribute to a public forum, which still feels to many like a chore rather than a natural part of the academic workflow. I’ve had to think much more practically about strategies for making space for DH in the institution when co-writing a report on sustainability in digital scholarship.

As Brandon McFarlane mentioned in a previous post, the divide between my DH interests and my “day job” as a “vanilla” scholar (talking about the politics of that terminology would take a whole ‘nother post) often leaves me feeling like I have multiple, conflicting identities. But the solution, I’m beginning to expect, cannot be an all-or-nothing approach. The world is going digital, and scholarship is inevitably going with it, but it seems more likely to be little by little before it’s all at once (to clumsily paraphrase Blanchot). Instead of thinking of myself as divided between two worlds, then, I’m trying to think of myself as a bridge. I can talk to DH-wary scholars about how the incorporation of digital tools might make our research more theoretically rigorous, but I can also bring my non-digital theory training to bear on a rigorous critique of the blind spots in DH. I can talk to the contemporary CanLit crowd about data mining and visualization without having to play the part of a DH evangelist. I might even be able to incorporate a ripple of DH into my vanilla dissertation… and if not, I will sure as heck tweet about it.

What about the rest of you? Have you experienced a disjunction between DH and the day-to-day world of the Canadian academy? Are you finding ways to overcome this disjunction? What other strategies might we adopt to find productive dialogues between our different research worlds?

June 12, 2011

Digital Editions @ DHSI: 2011 Version

This past week, I had the opportunity to teach a course on digital editions at the Digital Humanities Summer Institute with Matt Bouchard and Alan Stanley. It was my first time as an instructor at DHSI, and I was filled with nervous excitement on Monday morning. What I wanted to do with the course this year was to offer a holistic approach to building a digital edition that challenged the participants to think about their projects not only as a whole, but also as iterative and modular. The two themes that I tried to highlight were the importance of project management and the user-experience design. We talked quite a bit about planning and project management, workflow, information architecture, and for the first time, we worked with the alpha version of the Islandora editing toolkit.

All in all, I think the course went very well! Below are some of the highlights. I’ve included my classroom slides and handouts in the hopes that these materials will be useful for those who were unable to attend the course and who may be beginning to think about building a digital edition, and for anyone who is interested in what we were up to this week!

Day 1 Overview

On the first day we began with an overview of print editions, and talked a little bit about some of the benefits of text-based versus image-based digital editions. The class came up with quite a substantial list of the elements that comprise a print edition, including:

timlines/chronology

glossary

static pages

page numbers

running headers

marginalia

provenance

book cover

dust jacket

reviews

bindings

bibliographies

biographies (author, editor)

table of contents

footnotes

endnotes

critical introduction

appendices (contextual, editorial)

errata strips

publisher information

typography/font

stitching/glue

whitespace, gutters

watermark

end papers

title pages

section pages

copyright

images (photos, illustrations)

dedications

acknowledgments

I encouraged students to think about these elements as they began to to conceptualize their digital editions. Many or all of these features might need to be included in a digital edition, and the challenge was to think about how we might represent them digitally. I also gave a very brief introduction to some of the current tools and platforms available for building digital editions. In the afternoon, we worked through a “Site Audit” of some existing digital editions, and considered what worked (and what didn’t) in the digital editions that are currently available.

Slides for day 1:

Day 2 Overview

On day two, we focused on project management. Borrowing heavily from Jeremy Bogg‘s work, I talked about the importance of thinking of the project in terms of different phases. Then I introduced the ever-so-important “Scope Document”, and asked the students to spend some time conceptualizing their project(s) as a whole. I suggested that before beginning to implement (read: code) a digital project, one must consider the project from multiple perspectives and have a rock-solid scope document and technical / feature specification in place. Building a project in phases allows for an iterative process that keeps the project moving forward, without the too-often paralysis that faces digital humanities projects that suffer from scope creep (or, more often, scope explosion). Instead of starting to code an entire collected works, I argued, try starting with a small subset that can serve as a robust working model for the project as whole.

I provided a handout with a long list of questions to ask at each stage of the project. These questions are meant to serve as a guide for project planning (and, if you so choose, a grant application).

Phase 1: Strategy / Project Objectives

- What kind of edition are you creating? Why?

- Why is your project important?

- What’s already available?

- Who is your audience?

- What are the limitations of your project?

- What approach or methodology will the project follow?

- What are the major dates or milestones for key points?

- How will you determine whether your project has been successful?

Phase 2: Scope

- What features would you like to include in your edition?

- What tools and technologies will you use (Islandora/Drupal, Image Markup Tool, Simile Timeline, JUXTA)?

- What kinds of questions can you ask of your data using text analysis and data visualizations? (This will impact the platform and technology you choose)

- Do you have technical skills or will you be working with a developer?

- Who will be involved in the project, and what will their responsibilities be?

- What specific components are needed on the site? What technologies? Static HTML? Need dynamic content? Need a CMS? Need a custom web application or interactive features?

- What tools would you like your project to be compatible with? Is there a specific data format you will need to use?

Phase 3: Content

- Create a sitemap that will determine how content is categorized and contained within the overall structure of the site

- Inventory of content: what will you put on each page? In each section?

- What kinds of materials are you using? General description? File formats?

- What is the relationship among different pages, images, texts, tags, categories, etc?

- How will users interact with your content? (Search, manipulation, view?)

Phase 4: Design

- What do you want to communicate?

- What do you want users to remember?

- How do you want users to respond?

- What are some “benchmark” editions that might influence your design process? (Site Audit)

- What do you like about these designs? Why?

Slides for day 2:

Day 3 Overview

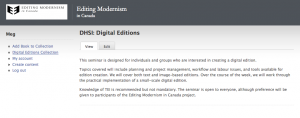

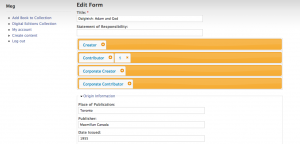

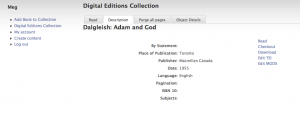

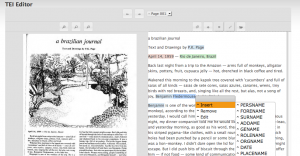

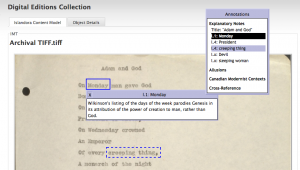

On Wednesday, we moved into some hands-on technical work, and had the opportunity to begin using the Islandora editing system for the first time. Islandora is an editing workflow that integrates a Fedora Commons backend with a Drupal front-end. EMiC is working in partnership with the great folks at UPEI to create a fully-functional editing toolkit that allows users to pull materials from the commons (housed in the Fedora repository) and edit them in a web-based environment. Alan Stanley was an invaluable asset, and the testing and editing process would not have run as smoothly as it did without his help on the ground. It seemed like every time we found a bug, Alan was able to step in and fix it almost immediately.

Here are a few screenshots of the system:

The login screen and home menu:

MODS metadata editing for a Book object:

Object Description page:

TEI Editor:

Image Markup Tool Integration:

The participants in the digital editions class showed remarkable patience and understanding working with a tool that, at its core, is still in alpha phase (pre-alpha, even). Thanks to everyone in the class for serving as the first user-testers for the Islandora editing suite. At times, I’m sure you felt more like bug hunters than editors, but please know that your feedback will be invaluable in the development of the EMiC/Islandora editing workflow. Kudos!

Day 4 Overview

Once we’d had a chance to work with some of the technical aspects of editing a digital edition, we took a step back and talked a bit about design. I argued that design is visual rhetoric, and that as editors, it is as important to think about aesthetics as it is to consider content. In fact, I would go so far as to say that in building digital editions, form and content are inseparable. Good design, built with the user-experience in mind, often means the difference between a usable and unusable tool. On the afternoon of day four, participants worked on various aspects of their projects, depending on what they deemed most important to them.

Slides for Day 4

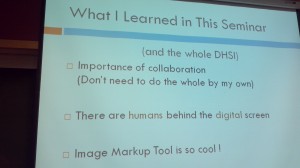

Day 5 Overview

On Friday morning, each person in the class gave a brief presentation of their projects and what they learned this during the course. I think Yoshiko’s slide captures the week quite aptly:

Over the course of the week, the students worked through site audits and project scope documents, design specifications, user personas, and wireframes for their digital projects. We talked a lot about designing for the user experience and the importance of bringing together form and content. “Modularity” was certainly the word for the week, and I hope that the students left with a solid understanding of all of the various pieces (and people) that are part of the process of creating a digital edition. Thanks to all of the participants for your generosity, patience, engagement, and brilliance. I had a fabulous week, and I hope you did too!

June 10, 2011

Thinking through User Personas

In Meg Timney’s Digital Editions course at DHSI 2011, one of the concepts that was new to me was the development of user personas in planning a web-based project. For many of us, the users that we want to ideally attract need to be tempered by the users who actually may use the site. We need to design for multiple audiences, and we always need to be thinking (in my mind, anyway) about our most basic, least informed reader. We need to be sure the site is user- friendly. It is going to be a pedagogical tool, and as a result, we need it to be intuitive enough and accessible enough that even the “Bobbie Le Blaw”‘s of the world will be connected to our work. By working through this process, I was forced to think more about user needs and competencies.

I have made this (kind of silly) user persona document as an initial way to think through our site as it will be used, instead of just how I would like it to be used. Maybe this kind of thinking will be a helpful way for you to map out your own audiences, and acknowledge for yourself some user needs you had never thought of before.

User 1: Disengaged Student User

Bobbie Le Blaw is a fourth year student in a second year class. He majors in sociology, but thought he could take a couple of bird courses to coast his way to the finish line. He is not particularly familiar with the field, and has no interest in becoming more informed. He will come to the site if it is for an assignment approximately 12 hours or less before the due date. He needs to access information quickly, and is way too impatient to read instructions or engage in a multi-step process. He will click on two or three icons, want to copy a selection of text, and then get back to his twitterfeed.

User 2: New Scholar

Liz Lemler loves poetry and F.R. Scott. Ever since she read Sandra Djwa’s biography of F.R. Scott, she has wanted to know more about McGill Fortnightly, Preview and First Statement. She has decided to use these primary materials in relation to the published poems in books and anthologies to construct a first class final essay. She has never looked at a periodical online before, but she is eager to please. She wants the guideposts clearly laid out, and an FAQ and about this page. Because she always strives to get an A, she also seeks out links to other secondary sources and biographical material from related projects. But, since this is all new to her, she needs the steps to be clear and straightforward.

User 3: Seasoned Scholar

Dr. Spacesuit is an Assistant Professor who is working on his second monograph. Having recently published a book on Gender, Modernism and Dirty Socks in Canada, he plans to extend this framework to other forms of soiled laundry. Already familiar with digital technology, he is interested in searching specifically for literary references to discarded or filthy clothing, and textile items that retain harsh odours. Having developed his own set of keywords, Dr. Spacesuit wants to used advanced search features so that he can compile a database of these references across genres in music, film, poetry and drama.

User 4: French Scholar

Mme Histoire is shocked to learn that a group of English Candians have developed a robust website about Quebecois periodicals. The images of the magazine are in French, as are the transcriptions, but she is disappointed to find that the surrounding content is in English. She has a passing knowledge of English, but as her second language, she relies heavily on Google Translate to navigate the website. She likes consistency and icons that are repetitive to allow her to navigate the site without fluent English. If she could print off the images with ease, she would like to make a handout or slideshow for teaching.

(With thanks to i-stockphoto.com for images)

June 7, 2011

DHSI=>DEMiC=>Digital Editions

At our DEMiC 2011 orientation session, I had a chance to welcome 30 EMiC participants to the Digital Humanities Summer Institute at the University of Victoria. Or, rather, 31 including myself. A long month of EMiCites. This is our largest contingent so far, and DHSI itself has grown to host over 200 participants attending 10 different courses. The EMiC community is represented at DEMiC by 13 partner institutions. EMiC has people enrolled in 7 of the 10 offered courses. But what really makes DEMiC 2011 different from previous years is that EMiC is offering its own DHSI course.

If you’re already dizzied by the acronyms, this is how I parse them: DHSI is the institute in its entirety, and DEMiC is our project’s digital training initiative that allows our participants to take any of the institute’s course offerings. With the introduction of EMiC’s own course, DEMiC has transformed itself. EMiC’s Digital Editions course draws upon the specializations of multiple DHSI course offerings, from Text Encoding Fundamentals to Issues in Large Project Management.

The course has been in the making for roughly six years, beginning with the pilot course in editing and publishing that Meagan and I first offered at Dalhousie in 2006-07. This course was not offered as part of my home department’s standard curriculum, which actually proved advantageous because it gave us the freedom to develop an experiential-learning class without harbouring anxieties about how to make the work of editing in print and digital media align with a traditional literary-studies environment. In other words, we started to develop a new kind of pedagogy for the university classroom in line with the kinds of training that takes place at digital-humanities workshops, seminars, and institutes. To put it even more plainly: we wanted to import pieces of DHSI to the Maritimes. That was pre-EMiC.

With EMiC’s start-up in 2008, we began flying out faculty, students, and postdocs to DHSI. After two years (2009, 2010) of taking various DH courses at introductory, intermediate, and advanced levels, we consulted with the EMiC participants to initiate the process of designing our own DHSI course. Meagan and I worked together on the curriculum, and Matt Huculak consulted with both of us as he surveyed the various options available to us to serve as an interface and repository for the production of EMiC digital editions at DHSI. After six months of trial and error, weekly skype meetings with about a dozen different collaborators, three different servers, and two virtual machines, we installed Islandora with its book ingest solution pack. That’s what we’re testing out in Digital Editions, keeping detailed logs of error messages and bugs.

I would like to thank the many people and institutional partners who have come together to make possible the first version of Digital Editions. This course is the product of an extensive collaborative network: Mark Leggott’s Islandora team at the University of Prince Edward Island (Alan Stanley, Alexander O’Neill, Kirsta Stapelfeldt, Joe Veladium, and Donald Moses), Susan Brown’s CWRCers at the University of Alberta (Peter Binkley, Mariana Paredes, and Jeff Antoniuk), Paul Hjartarson’s EMiC group at the UofA (Harvey Quamen and Matt Bouchard), EMiC postdoc Meagan Timney at UVic’s Electronic Textual Cultures Lab, Image Markup Tool developer Martin Holmes at UVic’s Humanities Computing and Media Centre, and EMiC postdoc Matt Huculak at Dalhousie.

As I write this at the back of a computer lab at UVic, fifteen EMiC participants enrolled in Digital Editions are listening to Meagan, Matt Bouchard, and Alan walk them through the Islandora workflow, filling out MODS forms, testing out the book ingest script with automated OCR, and editing transcriptions in the web-based TEI editor. Some people are waiting patiently for the server to process their ingested texts. We’re witnessing the first stages of EMiC digital editions of manifestos and magazines, poems and novels, letters and short stories. We ingested texts by Crawley, Livesay, Garner, Smart, Page, Scott, Sui Sin Far, Watson, and Wilkinson. And we’re working alongside an international community, too: our newly born repository is also populated with editions of D.G. Rossetti, Marianne Moore, Tato Riviera, Hope Mirrlees, Catherine Sedgwick, and James Joyce.

This afternoon the server at UPEI processed 20 different texts. Hello world. Welcome to Day 1 of the EMiC Commons.

June 5, 2011

Editing Le Nigog, Part Two: Advertisements

One of the primary goals of our Nigog periodical project is to re-socialize the text in its original context via a digital edition. Periodicals have often been divorced from their context through the binding process, where the original advertisements were disregarded, leaving only the articles in libraries across the world. Advertisements, often printed on newsprint with separated numbering, could easily be torn out before the magazines were bound into volumes. This “hole in the archive”, as framed by Robert Scholes and Clifford Wulfman, removes the important interplay between two sides of modernist periodical production. On one page, the little avant-garde magazines make manifestos and demand a critical rethinking of art and culture, but on the next there could be an advertisement for cigarettes, clothing or other luxury middle-to-upper class goods. Many magazines depended on advertising revenue to stay afloat. The consumer messages of the advertisements, in part, create the space and conditions for the rest of the content. By placing the content back in its social situation by recovering these important pages, we make great strides in understanding the broader intertexts that shape the magazine’s diverse reading publics.

At Congress last week, Matt Huculak and I presented some preliminary research on Le Nigog focused on its advertisements. It is these issues that I want to briefly touch on here. Le Nigog’s advertisements are integral to properly socializing the text within the Montreal reading public it actively established and served. In the first ten issues, there are over 300 advertisements, with an average of ten pages of ads per issue. Though the advertisements are integral to our understanding of the text’s materiality, no reprint of the text to date has included them, and thus their role in establishing Le Nigog as a part of larger social and economic networks in Montreal has not yet been examined.

First and foremost, the advertisements of the Nigog offer us important data about readership demographics: not only what they were buying, but also what else they were reading, the kinds of cultural activities they may have pursued and the simple geographic area they were likely affiliated with. Most of the advertisers are clustered largely in downtown Montreal, where the meetings took place and where the editors could be reached by mail. I created a basic visual map to loosely plot the advertisers based on the addresses provided, which I will post after DHSI in Victoria.

The blue/purple marker on the map is the home of Robert Laroque de Roquebrune, the editorial headquarters of the magazine. Clustered around it, in red, are the business addresses. When the digital edition is created, the map will be corrected to match with 1918 landmarks and street

numbers, and we will be able to provide more data on the individual businesses and their products, as well as the frequency with which they appeared in the magazine. Many of these markers actually represent multiple businesses within the same building, something that will also be more clearly differentiated in the final edition.

A large portion of the advertisements are for Montreal libraries of different sorts: bookstores specializing in multiple languages, rare books, and magazines, as well as multi-purpose bookshops where you could also have embroidery work done, buy specialized stationary, bind your books, or even have some printing done. Librairie C. Déom, for example, features prominently in each issue of the magazine on the first page. This bookstore is touted as the dispensary of the Nigog. As the ad promises, the books featured in each issue were stocked alongside the magazine, marking the Nigog’s place within a larger, international print culture. Instead of simply accepting what was read within the magazine, the reading public of the Nigog is asked to actively engage in the discussion and contribute to the articles. A page long advertisement at the end of the first issue pointedly affiliates itself with established magazines and journals, creating an intellectual “to-read” list. Like the manifesto of the journal itself, the advertisers are invested in building up print culture in Canada, and here rely on expanding the existing framework to

include more focused, specialized discussions of the arts for middle-brow readers.

Ideally, our advertising database will also be able to demarcate and extend the multiple links between the advertisers and contributors. For example, of the five musicians offering lessons in the magazine, two are contributors: Leo-Pol Morin and Rodolphe Mathieu. While their articles attempt to extend the discussion of modern music and establish their critical authority, their advertisements are quite traditional: Mathieu offers lessons in musical theory, harmony and counterpoint, while Morin offers piano lessons. These specialists use their criticism to sell their services, and also to generate an audience for their own recitals and public performances. Morin in particular also uses the advertisements in this way, with three issues advertising a performance in April, two of which include a full program. Morin’s agent, Henry Michaud, also advertises within the first few issues of the magazine, offering the middlebrow music-for-hire at parties and events of various sizes. This advertisement uses several markers to establish authority in the field: Michaud is affiliated with “the Standard Booking Office” in New York, and his clients include two artists with signed record deals from Columbia Records.

The avant-garde artists, writers and architects in Montreal that contribute to the magazine exist in a tightly knit social web. As we begin to read the advertisements in relation to the content, new and complex relationships are brought to light. We are not only able to read Canadian modernism in new ways, but we are also able to more fully historicize and socialize what we read in the diverse culture milieu that brought it into being.

See Also: