Archives

Archive for the ‘Research’ Category

August 1, 2014

Ethical Editing and the Digital Deluge

I’m something of a newcomer to DH, but what I enjoyed most about TEMiC 2014 was the alternation between practical matters and more abstract, wide-ranging theorizing. Workshops on specific sites and tools such as Spoken Web, the Modernist Commons, and Audacity gave way to discussions about the ethics of editing or reissuing a variety of texts. While some initiatives — such as several participants’ work disseminating Canadian poetry readings and other phonotextual materials — seem to be largely unproblematic examples of preserving work that could otherwise be lost or neglected, projects involving Indigenous cultural materials could be substantially more fraught (as Dean Irvine pointed out during his talk on Tuesday).

Such discussions, along with Karis Shearer’s and Jordan Stouck’s comments on the politics and ethics of dealing with correspondence containing contentious subject matter, made me reflect on some potential difficulties in my own work with EMiC. I pitched my project — a digital edition of Laura Goodman Salverson’s fascinating yet fairly melodramatic novel The Dove, in which a village of Icelanders is captured by Muslim corsairs and taken to Algiers — with the intention of disseminating what I thought was a richly bizarre iteration of the internationalist and imperialist concerns central to much modernist and Canadian literature. During TEMiC, I came to be aware of a range of possible objections to such a stance. Would those with a close connection to Salverson’s autobiographical writings or earlier novels consider her foray into historical romance to be in poor taste? If the edition’s target readership consists of a body of scholars with a particular set of interests, could the novel in fact be better off shrouded in some degree of obscurity? More practically, who would benefit from an elaborate genetic edition that incorporates many extra-textual features? Would it be wisest to prepare a very basic yet widely accessible edition? During one discussion I found myself arguing in favour of critical editing that produces sufficient collective enrichment — whether knowledge-based or aesthetic — to make the project more than an arbitrary digitalization of one’s research interests. And while many of the week’s readings and demonstrations of digital tools contributed to an atmosphere of limitless possibility, perhaps it is naïve to think in terms of a vast sea of lost texts that would be best served by preservation as digital editions or databases. Maybe Dean’s ideas about beginning a process of recovery and leaving open the possibility of walking away are relevant not only for projects involving sensitive Indigenous texts; perhaps truly responsible editing practices have to involve a surgical use of well-selected technologies for carefully thought-out purposes rather than be based on enthusiasm for the possibilities opened up by emerging digital technologies. I’m the kind of person who frets about most things, but last week’s discussions have nevertheless encouraged me to think more deeply about how to proceed with my edition.

Thankfully, however, these worries dissolved in waves of screen prints and sushi and seasonal beverages, not to mention the literal waves of Okanagan Lake. Much as my brief swims provided valuable respite from the patrons of the Centre of Gravity music festival (see also: the Bro-nado), I hope my use of digital editing methods results in a useful, if necessarily modest, final product.

July 30, 2014

“The Text Has Shattered”: The 2014 TEMiC Conference

For me, TEMiC 2014 was a week of “firsts”: I finally got to visit UBCO’s gorgeous campus; I was introduced to several new and valuable digital tools, including PennSound, the Modernist Commons, and the WayBack Machine; and I made a successful silkscreen print with Briar Craig during his Monday workshop, even if my wildly unsteady hand caused him to question my sobriety. At the same time, it was a week of “lasts,” if I am correctly recalling something that Dean Irvine said during Monday’s seminar: “After this week, you’ll never look at a text in the same way again.”

I will admit that Monday morning initially caused me some anxiety; there I was, preparing to give a presentation regarding John Bryant’s “Pleasures of the Fluid Text” in front of a room composed primarily of people who had considerably more experience with academia than I. However, my anxiety quickly gave way to ease and excitement, as I realized I was surrounded by a warm and welcoming community of people ready to share their genuine passions for literature and textual editing. This, I thought, is going to be an incredible week.

My suspicions were confirmed as the days went on, and I found the morning seminars to be one of the most enjoyable parts of TEMiC. Armed with a solid framework of theoretical scholarship and a questionable diet of Tim Horton’s pastries, each participant’s engaging presentation provided an excellent springboard into conversations that continued long into the afternoon. It was refreshing to see a mixture of theory and praxis at work, and projects like Nick’s WatsonWalk and Lee’s Spoken Web archive helped demonstrate examples in which literary studies can manifest in practical, enjoyable, and accessible ways. Whether discussing indigenous oral traditions, digital and audio recording, or simply the anagrammatic possibilities of TISH magazine, everyone’s unique projects and personal experiences helped propel each others’ understanding of textual studies to places we never thought possible.

Following each day’s delicious lunch in the atrium, we had the absolute pleasure of meeting a total of five guest presenters who furthered our discussions on textual editing and digital humanities. From Paul Seesequasis’s discussion of Aboriginal knowledges and textual representation to Miriam Nichols’s complex transcription of the “Astonishment Tapes”, it was once again useful to bring together various experiences and apply these examples to build upon our morning conversations.

I suppose I will conclude by recalling a word which was continually emphasized throughout the week: collaboration. One of the most vital aspects of TEMiC for any participant is the opportunity to meet with other students, faculty, and individuals from around the country with varying academic backgrounds and personal interests. During our very short time together in Kelowna, I witnessed countless examples of people sharing ideas that helped broaden everyone’s intellectual scope and make connections that will remain as lasting friendships.

As our plane took off and I headed back towards the distant shores of the Maritimes to resume my work on Canada and the Spanish Civil War, I felt changed by my time at UBCO. Maybe it was the scorching sunlight and over-consumption of breakfast sandwiches finally taking their toll; but more likely it was the comforting discovery that the post-undergraduate experience is less intimidating and terrifying than my mind sometimes envisions. I find it can be easy to compare oneself to others and stress about your own abilities or that one project you’ve been putting off; but at the end of the day, having sushi and a pint in the company of great people can be just as enlightening and fulfilling as an hour spent reading or plugging paragraphs into a Word document. If the 1963 Poetry Conference taught me anything, it’s that great ideas and pedagogy don’t come from a single mind, but from a group of them working together towards a common goal.

By Daniel Marcotte

July 29, 2014

Check Your Egos at the Door

This week was my first TEMiC at UBC Okanagan and I had no idea what to expect. The weather wasn’t nice enough to corroborate our bragging to the rest of the country, but being able to sleep with a blanket for a change was a nice consolation.

Taking the course as an undergrad was a bit intimidating at first. There were so many brilliant people in the room with various letters in their titles. The intimidation was short lived, however, as the group of participants at the summer institute were some of the kindest and welcoming people I’ve had the pleasure of spending forty hours over five days in a room with one wall of windows.

I was assigned the Charles Bernstein article, “Making Audio Visible: The Lessons Visual Language for the Texualization of Sound”. As part of my course credit I gave a seminar-style presentation on this article. It was nice to have the opportunity to present scholarly work in that seminar format as I have never done this before. I had a lot of great models to aspire to from watching other folk’s presentations throughout the week. It was a great learning experience in a new style of presentation. I also got the chance to really study Bernstein’s work more “closely” (see what I did there? ‘cause close is like close list—ahh forget it). Searching for videos of his talks on PENNsound and Youtube, I found myself listening for hours to Bernstein talk about things that did not pertain to my presentation at all. That man is a genius.

Other highlights of the week for myself include: The Stouck’s eye opening talk on Canadian writer, Sinclair Ross; Kaplan Harris’ breakdown of the economic differences between large and small publishers; and Miriam Nichols’ wonderful talk about the astonishment tapes. I was privy to the last one as it was so relevant to my own work on Warren Tallman and the TISH folks. It was great to hear someone talk about that time in Canadian history who experienced it first-hand.

Early in the week, Dean Irvine said something to the effect of “the reason why this institute works is because all the people who take part check their ego’s at the door”. That’s not to say that the people involved have egos in the negative sense, rather that they are so accomplished that they would have the right to rub it in all our respective faces. But Dean was right, everyone was inclusive. The dynamic of the group facilitated a confident week of navigating dense reading material, brilliant speakers, and gratuitous use of words with north of five syllables. I feel fortunate to have had the opportunity to get up before noon to learn and smash clocks with such fine people. Especially that Cole guy, man he was great. These posts are anonymous, right?

By Cole Mash

July 26, 2014

Wednesday.

“Make It Blog” Pound famously ordered, and Kailin expounded the weight of the decree: Publish Or I’ll Perish You (though perhaps I exaggerate).

The famous EMiC blog! The weblog. We-be-loggin #TEMiC2014, on a day-to-day schedule.

In the naivety of Monday I assumed that signing up for Wednesday’s scheduled blog-entry would leave me plenty of time to absorb some of the ample brilliance on display and spin it into the requisite 500 words, all before a quick swim in Okanagan Lake with Carl. But now it’s Friday and, as Rebecca Black always said, gotta get it done on Friday (especially important advice given that The Way Back Machine is very poorly named indeed (though still impressive)).

Somehow the week disappeared into a blur of stimulating seminars, delicious lunches, outstanding plenary speakers, wonderful workshops, adventurous automobiling, dinner-and-drinks(+), and late-night debates about the potential existence of a man named Marcel Duchamp (hint: he’s a real thing and an enthusiastic scrap-booker). Should I still write about Wednesday, as I promised all those other days ago? Should I attempt to remediate the performance of the day onto The Famous EMiC blog!, striving in vain for an authentic representation of the immediacy and original intention of all those users/actors/readers/writers/performers/speakers/places/materialities/bibliographies/double- and triple-helixed codes of hump or slump day? I’d try but my notes blew out of the car’s window on my drive over here and I don’t think that Karis had that webcam running and there don’t seem to be any recordings of the day on PennSound or SpokenWeb or YouTube. Anyway: Onward!

Tuesday morning I talked about the WatsonWalk app, which I worked on with the EMiC UA group. Our earlier discussion of archives and projects Tuesday had turned towards the importance of collaboration and Dean had argued that most people need to be taught how to collaborate—it’s not an automatic process that leaps successfully from a group. Dean’s point is a good one and I added to it only that people need instruction not just in general ideas or theories of collaboration as an abstract notion but also in practical specifics of collaboration: how can a team meet most productively, how does work material circulate (on-line or off), who keeps track of what’s happening (documentation), how does the workflow change, etc.? The collaboration that emerged around the WatsonWalk app was shaped by the humility and generosity of all the participants, especially Paul and Harvey, the project leaders. Projects without such patient leadership and without training in collaboration undoubtedly produce the horror-stories that emerge all too often in which collaboration degenerates into the hierarchical allocation of labour. Building on Julia’s earlier points about the importance of art and design in digital projects, I also noted that collaboration with artists and designers needs to happen from the initial stages of any dh project. Literary scholars generally aren’t very good at graphic design and programmers generally think that the blinking green text of the command line is pretty enough. Including a designer from the outset saves time, money, and effort. I talked also about the content of the WatsonWalk app, but that’s been done elsewhere and the best way to see how it works and what it contains is to download and play with it!

But that was Tuesday, not my Wednesday. Wednesday afternoon Paul Seesequasis, editor-in-chief of Theytus Books in Penticton, visited to talk about Big Bear, Queen Victoria, difficulties of translation, tricksters, scholarly depictions of “The Canadian Indian,” and tongues planted firmly in cheeks. In the morning seminar we had discussed, among other things, the nature of “the oral” and “oralities,” and the difficulty of shoe-horning all types of oral performance into systems designed to manage textual material. If textual artefacts are subject to the double-helix of linguistic and bibliographic codes, as McGann convincingly argues, what words do we have for describing the codes that govern texts that are distinctly non-textual—not bibliographic—including oralities and a range of other “performances”? Borrowing from Genette’s notion of the paratext, how about paraformance? Oral texts as structured by a double-helix of linguistic and paraformative codes? I like it.

The paraformative elements of Seesequasis’s plenary included a wry smile, a big belt-buckle, and an unreliable lapel mic held in his sometimes-waving hands, which meant that his voice came and went and there were gaps in his speech to be minded. Was he, even then, hiding the good stuff in those gaps? Was he performing a tricky sleight-of-hand as he fumbled through the unhelpfully named images on his computer, searching for the right one, reminding that he could have used PowerPoint but didn’t—was there another story being told in the repeated opening and closing of the images we’d already seen or somewhere on the desktop in the background? Was he teaching us the pleasure of frustration as he showed us those guys on the golf course again and again? Someone asked about humour and he said that situations that lack humour are generally bad ones.

A trickster must have installed this handrail off the stage:

Wednesday evening many of us put into practice all we’d learned about oral remediation as we sat around talking, telling stories of varying pertinence and volume, and as we talked we and our stories grew a bit fuzzy around the edges and the cheeks of our stories may have glowed a little but campus security didn’t seem to mind, yet. And out of Wednesday, and all the other days, wonderful connections developed between the participants of TEMiC 2014—collaborative projects, intellectual exchanges, and, I’m sure, lasting friendships.

I thoroughly enjoyed UBCO and a great many thanks to everyone in attendance and to Karis, Dean, Cole, and everyone else involved in organizing the week—or at least in organizing up to Wednesday: I wouldn’t want to step on the toes of whomever was press-ganged into remediating Thursday and Friday…

July 24, 2014

Adaptation

This being my first TEMiC, I wasn’t sure what to expect. It’s been awhile since I attended a course away from my home institution, and have really only travelled alone to briefly attend conferences. Add to this the uncanny phenomenon of re-encountering (after x years) the ‘residence experience’, wherein I shed the creature comforts of cable television, WiFi, and a private washroom. Not only that, but I couldn’t shake the sensation that my project and background as an artist/curator-slash student of Interdisciplinary Humanities are somewhat anomalous and amorphous when compared with those of other EMiC participants (I believe this is commonly referred to as ‘imposter syndrome’) and that this would alienate me, so, needless to say, I was nervous for the first official day of training.

This is where the complaints end. On Monday, the official start day of the course, I had been here for two nights and had adjusted to the ‘residence situation’. I had attended the welcome dinner and had found that I had much more in common with my fellow participants than expected, and felt must less insecure. The first day involved a discussion of some of the basic tenets of editorial theory, which are interesting in themselves, but it was really the discussion of our assigned readings that brought a sense of ease: theory, I can do.

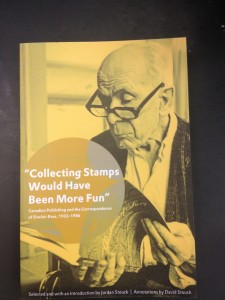

Face-to-face seminar discussion, as fraught as it can seem when I tend to second-guess the unformed thoughts I impulsively share with the group, is one of the most productive forms of communication in a pedagogical environment, and can bring a sense of unity to an otherwise disjointed and multifarious group. Add to this a brilliant presentation by Jordan and David Stouck on their book project, “Collecting Stamps Would Have Been More Fun” (2010) and a print-making workshop (!!!) with the wonderful Briar Craig.

Tuesday was the day of my presentation on Susan Brown’s “Don’t Mind the Gap: Evolving Digital Modes of Scholarly Production across the Digital-Humanities Divide” (2011), and although I was disappointed to hear that Brown wasn’t able to attend the afternoon session at the UBCO theatre, there was an interesting dialogue between my analysis of Brown’s paper (implicating the related conversations of critical posthuman theorists N. Katherine Hayles and Rosi Braidotti) my colleague Nick’s presentation of the creation of the Watson Walk app from the EMiC lab at U of A, and EMiC director Dean Irvine’s lecture on the history of avant-garde laboratories and collaboration and subsequent workshop on the development of the Modernist Commons.

The debate between traditionalists and digital humanists is central in some ways to my doctoral studies, as I have encountered critical perspectives regarding my interest in technological mediation and digital infrastructures. Encountering such enthusiastic and well-wrought arguments reinforcing the objects my curiosity was extremely refreshing, particularly because the milieu of a textual editing course would seem to lean, epistemologically and ontologically, more towards a traditionalist model. The notion that digital humanities implicates the advancement of new forms of literacy and expressive form, building and improving upon existing models of dissemination, is oddly comforting. Knowing that a community of scholars shares these interests will propel our research forward.

Reflecting on the past few days and anticipating the next few days of the training institute, the overall theme that comes to mind is that of adaptation. Sure, we have adapted to residence life and each other (it was noted that our seminars have become progressively more lively and animated), but on a different level, we, as both humanists and scholars capable of change, have adapted our projects and our individual and more collective levels of consciousness to the evolving digital climate.

By Julia Polyck-O’Neill

July 22, 2014

Developing Productive Strategies For Collaborative Projects

On day 2 of the 2014 TEMiC Institute, Julia Polyck-O’neill presented on Susan Brown’s article “Don’t Mind the Gap: Evolving Digital Modes of Scholarly Production Across the Digital-Humanities Divide.” Following the presentation, our group discussed what Brown identifies as the dialectical relationship between the computer sciences and the humanities aspects of the digital-humanities. Having explored the dialectics of collaborative work in the “A Collaborative Approach to XSLT” course as part of DEMiC at DHSI, and previously blogged on the pedagogical nature of this type of work, I believe it to be useful to synthesize some of the ideas that surfaced during our talk.

Below are the core questions from this morning’s conversation:

1) How can a collaborative digital editorial project’s team, which consists of literary scholars and computer scientists, gain the most from this type of relationship?

2) In a project that includes members with different expertise and expectations, can/should hierarchical relationships be avoided?

3) Since every member contributes differently, how do we try to ensure the satisfaction of each team member?

Following our discussion, here is what I have learned, if not been reminded of: Dialectical work should be exactly what its name suggests, dialectical. That is to say, a project should not be dominated by any individual, but rather should encourage a team effort where alternative ideas and approaches are welcomed. I am not suggesting that designating a leader is an unproductive strategy, but that the leader, as a member of the group, should not be above the team. Instead, its members should recognize that everyone depends on each other for the success of the project, and should understand the potential value of varying perspectives and differing expertise. In addition, a team is a living organism, it should be willing to adapt, and should always remain dynamic. However, what must remain constant is that the many relationships within the team should always be mutually beneficial for each member; and, perhaps most importantly, credit ought to be given when it is deserved.

Although these core ideas might appear to be obvious, it is often easy (especially in the heat and chaos of editorial projects) to lose track of what makes the team aspect of these collaborative projects so useful. For this reason, I am thankful to be here at TEMiC where I am reminded of the importance of collaborative work, and how to efficiently maintain productive relationships.

July 22, 2014

Narrating, Marketing, and Editing the Pause Between

Day 1 of TEMiC: The Okanagan edition

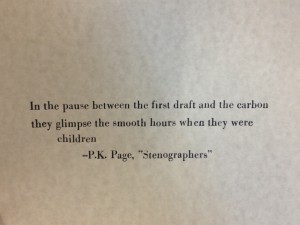

We kicked off the first day of the Theories of Editing Modernism in Canada (TEMiC) course with discussion of how the market shapes scholarly and creative output. A discussion anchored with examples of the differences between editions of Michael Ondaatje’s Billie the Kid and Atwood’s “This is a Photograph of Me” and The Journals of Susanna Moodie. The beauty of the white space that faces “This is a Photograph of Me” is lost in many anthologies that leave no room for the blank page. Canadian literary awards offer another instance of the marketability of literature; a market that more and more perpetuates the relationship between literary weight and physical weight: the books nominated for the Giller and the Governor General’s award seem to be growing in size, getting longer and longer. So, what are we, as scholars, as readers, in the market for? The reigning question at the end of Day 1’s morning session was: how do we define reading pleasure? Is it the pleasure of the interrupted text with scholarly apparatus? Or is it the pleasure of the plain text? And how is the market defining pleasure?

This issue of the market was picked up in the afternoon with guest speakers Jordan Stouk and David Stouk. Jordan and David spoke about Collecting Stamps Would Have Been More Fun; a collection of Sinclair Ross’s letters that has been aptly described as a “tragic novel” because it narrates Ross’s literary rejection. His book The Well exemplifies the demands of the market: the publishers shaped Ross’s book based on their projections of the market, but despite all these efforts, the market did not respond. Ross was left with a work that catered to the market, but the market was not buying. Jordan and David’s talk in part narrativized the blank place between Ross’s publications, the time of the rejections, the act of not writing and of not publishing.

In a letter to Margaret Laurence after the publication of The Diviners, Ross writes, “It’s the blank place that haunts the reader. There’s so much you don’t know—as you say, so much pain” (Feb 5, 1975). This passage resonates with the day’s discussion about market and speaks to the haunting pleasure of the white space and, to use a phrase from PK Page, “the pause between.”

How do you define reading pleasure? How do you negotiate different reading experiences in the classroom? Do you prefer an edition with a critical apparatus? Do students prefer editions with introductions, related essays, and critical material? How do you enter the text?

July 20, 2014

Staying the course: Research Plans, Motivation, and Pacing

Hannah’s recent post about staying energized has prompted welcome reflection on timing and pacing.

As a strategy to stay energized, I recently met with a colleague to create a 5 year plan and to chart out the years leading to tenure review. I find that meeting with colleagues in person helps to keep me motivated in the wake of energizing events like Congress, DHSI, and TEMiC. With a full teaching load from September to May, I always welcome the summer as a time devoted to research and writing; by July, however, something strange happens: I miss the structure and timetable that teaching provides. In the process of creating a 5 year plan, I realized the following:

1) I really need a 3 year plan as I prepare for tenure review.

2) I really really need a 5 week plan in order to accomplish key tasks before I go back to teaching in the Fall.

3) I also realized just how long major research projects take.

I ended up writing the same 3 research projects in years 1-3 in order to take into account revision and unforeseen inevitable delays. This process of rewriting the same goals helped me to focus on the long-term plan and . . . wait for it . . . to be patient.

Yes, patience was my take-away from the 5-year plan exercise: research projects take a long time from inception to realization, and that is ok.

In a way, my motivational exercise made me realize that it is important to stay energized but that it is, to borrow a tired metaphor, a marathon and not a sprint. And in the spirit of “energizing” old habits, let’s run with this metaphor, shall we?

I have been increasing my running mileage lately in preparation for a Midsummer Night’s run, which brings together my love of Shakespeare and running; these morning runs are done at conversational pace, a wonderful mix of enjoyment and challenge. This is the pace that I seek to set for my research: a pace that enables me to engage in dialogue with peers, colleagues, and fellow Canadianists; a pace that enables me to take the time out from my precious writing schedule to attend TEMiC; a pace with a run-talk, work-life balance.

To echo Hannah, how do you stay energized? Have you tried the 5 year plan? What are your strategies for staying on target with work goals?

July 15, 2014

On Figuring Out What’s Next

The Digital Humanities Summer Institute felt like a particularly whirlwind event this summer. As Melissa Dalgleish’s summary demonstrates, there was a flurry of blog posting matched by a spike in Facebook and Twitter activity, itself mirroring the busy thrill of seeing friends and colleagues in person. DHSI is always a perfect storm of excitement and exhaustion and inspiration, and every year I come out of it full of energetic determination: to Tweet more, to blog more, to read more widely in the ever-widening field of DH, to follow through on the thousand projects thought up over endless cups of cafe and drinks at Smugglers Cove.

- Infographic by Ernesto Priego. See http://epriego.wordpress.com/2014/06/09/digital-humanities-summer-institute-dhsi2014-in-text-and-numbers/ for more.

And yet, as soon as I return home, that energy begins to dissipate. All the other demands on my time, both personal and professional, step in, and Tweeting and blogging gives way to tucking articles into my Pocket for later. But this year, I’m determined not to let all that energy simply fade away.

Instead I’m crowd-sourcing the problem. I want to know how you, all of you, any of you, are taking that energy and moving it forward. What ideas, small or large, will go with you? What new projects or partnerships are you hoping to get off the ground? What tools or techniques will you be incorporating into your teaching and research? Let me know, and in the spirit of collaboration, let’s try to keep building this momentum.

June 20, 2014

New in the Neighbourhood

This year was my first ever experience of DHSI in Victoria, and it has been an awesome whirlwind of activities — meeting so many great people and participating in a lot of the colloquium and “Birds of a Feather” sessions. If I were to sum up the experience in a few words, it might be something like “excited conflict”. There is so much to see and do that it’s a little difficult not to become physically drained and mentally overloaded in just a couple days. Yet, at the end of the week, and even now, I find myself wanting to return for another heavy dose of the same, and wishing it was just a little bit longer.

The Course

I participated in The Sound of Digital Humanities course with Dr. John Barber, along with a few fellow colleagues I work with on a poetry archive project back at UBCO. Throughout the week, the course itself weaved through different focuses, and in between practicing basic editing in Audacity and GarageBand, there was much deep discussion about the nature of sound, theory, research, copyright, and the like. It is especially the latter discussion portion that I was keenly interested in, as we found that some others in the class were doing projects based on or around archives, and were tackling questions and concerns similar to what pertained to our project. It was an opportunity to not only listen and glean some greater insights from experts and generally brilliant minds, but to reciprocate it and impart some of my knowledge to others for application towards their own projects. The general atmosphere is… infectious enthusiasm: everyone is quick to offer their own valuable experiences and suggestions for solutions for others peoples’ projects — in some cases right down to the nitty-gritty technical details. In fact, come to think of it, it doesn’t stray too far from what you might find at a typical medium-sized gathering at a web development conference: some give talks on new cool techniques and technologies, and everyone is engaged in vigorous talk of theory and stories and jokes about working in the field, even over a couple pints at the pub. It was that kind of coming together and collaboration in our class (sans alcohol) which culminated with each of us putting a bit of ourselves into a sound collage representative of the broader aims of the Digital Humanities and our nuanced experiences in it. It was all at times (sometimes simultaneously) hilarious and poignant. Definitely not something I will forget any time soon.

New in the Neighbourhood

In addition to meeting new acquaintances, the week was also a time of reunion, where I was able to reconnect with my colleagues on our poetry archive project. It was a helpful and fun time for us to “regroup” — to reflect on the project’s progress, and also come back with new energy in thinking about ways of moving forward, with the application of some of our discussions both in class and within the larger DHSI hub.. For me, Chris Friend’s presentation on crowd-sourced content creation and collaborative tools yielded wonderful points about the benefits and perils of using such a model pedagogically. It has made me more particularly sensitive to how pedagogical functions might be brought to our archive, and what designs we might create (both visually and technically) to accommodate that.

On a more personal front, attending DHSI (and by extension, learning about the Digital Humanities as a field this year) has solidified a deep sense of belonging for me through moments of glorious serendipity, if you will; of happening upon something fascinating at the end of a long wandering; of searching for a place to call my “intellectual” and “academic” home. It is a place that beautifully brings together my major pursuits of web development, literary theory/criticism, and music, and collectively articulates them as the makeup of “what I do”. It has been one of those somewhat rare “Ah-ha!” moments where you find something that you were looking for all along, but didn’t know quite what it was.

It’s been a wild ride, but one that I definitely want embark on again. My greatest thank yous, all of my friends and colleagues — old and new — for such a wonderful experience. I look forward to when I can return again for another week-long adventure and “geekfest”!

Keep it “robust” my friends.