Archives

Author Archive

March 31, 2015

The Dove and the DH Guru of Indiana: The Carl Watts Story

It’s hard to believe that it’s been almost a year since I was given the go-ahead to begin my digital edition of Laura Goodman Salverson’s The Dove. When I got this opportunity, I knew very little about the Digital Humanities. It often feels like this is still the case; nevertheless, in the past year I’ve attained some practical skills, made some new CanLit discoveries, and embarked on a mission to help people who also feel incompetent as they take their first steps in the world of DH.

Although I had for some time been thinking about the relevance (or at least peculiarity) of The Dove, last spring I was suddenly overwhelmed with practical questions that needed answering. Scanning pages was easy enough, but some other basic steps were bound up with a slew of large and poorly formed queries: Is this the Tesseract I’ve heard about? How do I make it work? Can a lone man indeed create a digital edition on his laptop? Where does it go? During those early days in Kingston it seemed like there was nowhere to turn.

With the help of two fabulous colleagues (Google and Emily Murphy), however, I was eventually able to crack the code. The first colleague taught me how to generate reams of .txt files in which each gross stain on the pages of the novel was transcribed as a * or a Q. The second colleague solved my schema problem and pointed out some errors I had made in my TEI markup. This eleventh-hour save notwithstanding, I would describe myself as a master of DIY TEI. And while my basic TEI/XML markup is functional, my CSS skills are currently both DIY and LOL.

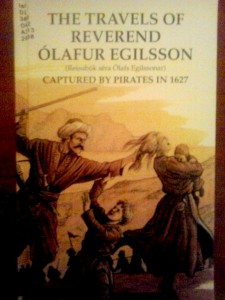

As I’ve been messing around with CSS, I’ve also continued researching the text’s history. I’ve always felt strange using the word “research” to describe my academic work; all this word ever really meant to me (as a graduate student) was frantically reading articles and then synthesizing them into either a term paper or an attempted publication. In contrast, having an entire funded year to read around a topic allowed me to make some actual discoveries. For instance, on my trip to view the typescript of the novel at Library and Archives Canada, I learned that Salverson made corrections with a green pen and that government employees enjoy eating lunch in food courts. As far as The Dove is concerned, I managed to uncover a consistent error in the small amount of writing that has mentioned the novel. These sources usually describe the text as based on an Icelandic saga, but my readings in this area revealed that this word usually refers to other, much earlier sources. Meanwhile, Salverson seems to have based her novel on one particular, somewhat different text: a seventeenth-century memoir entitled The Travels of Reverend Ólafur Egilsson. Much of the background research that led to this discovery has found its way into my introduction to the edition. This introduction is only about half finished, but when I mutter things to myself I definitely describe it as “masterful.” In the meantime, I’ll leave you with a picture of the memoir, which was conveniently translated into English for the first time in 2008:

I’m also fresh off delivering a grotesque Frankenstein’s Monster of a conference presentation at the annual meeting of the College English Association in Indianapolis. I started by describing my edition and discoveries, moved on to some practical tips regarding getting a digital-editing project off the ground, and concluded with a state-of-the-discipline rumination on textual communities and critical contexts in our early- or mid-DH epoch. Some audience members looked bewildered (in one case, disgusted), but when the session ended I was greeted by a lineup of people who either had technical questions of their own or were offering their thanks for being provided with a basic plan for getting started on a similar project. After having spent my early days struggling to answer such basic questions, I felt good knowing that I was now able to help people in similar situations. Perhaps some of the horrified looks I got during the presentation were merely reactions to the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, which was passed just as I arrived in the city. On that note, I took this picture of the Indiana Death Star shortly after I dubbed myself the DH Guru of the state:

As I move on to the next stages of the project, I want to thank Glenn Willmott, Emily Murphy, and Google for their advice. Also, obviously, a big thank you goes out to Dean and EMiC for allowing me to make progress on the edition and encouraging me to share my research and experiences.

August 1, 2014

Ethical Editing and the Digital Deluge

I’m something of a newcomer to DH, but what I enjoyed most about TEMiC 2014 was the alternation between practical matters and more abstract, wide-ranging theorizing. Workshops on specific sites and tools such as Spoken Web, the Modernist Commons, and Audacity gave way to discussions about the ethics of editing or reissuing a variety of texts. While some initiatives — such as several participants’ work disseminating Canadian poetry readings and other phonotextual materials — seem to be largely unproblematic examples of preserving work that could otherwise be lost or neglected, projects involving Indigenous cultural materials could be substantially more fraught (as Dean Irvine pointed out during his talk on Tuesday).

Such discussions, along with Karis Shearer’s and Jordan Stouck’s comments on the politics and ethics of dealing with correspondence containing contentious subject matter, made me reflect on some potential difficulties in my own work with EMiC. I pitched my project — a digital edition of Laura Goodman Salverson’s fascinating yet fairly melodramatic novel The Dove, in which a village of Icelanders is captured by Muslim corsairs and taken to Algiers — with the intention of disseminating what I thought was a richly bizarre iteration of the internationalist and imperialist concerns central to much modernist and Canadian literature. During TEMiC, I came to be aware of a range of possible objections to such a stance. Would those with a close connection to Salverson’s autobiographical writings or earlier novels consider her foray into historical romance to be in poor taste? If the edition’s target readership consists of a body of scholars with a particular set of interests, could the novel in fact be better off shrouded in some degree of obscurity? More practically, who would benefit from an elaborate genetic edition that incorporates many extra-textual features? Would it be wisest to prepare a very basic yet widely accessible edition? During one discussion I found myself arguing in favour of critical editing that produces sufficient collective enrichment — whether knowledge-based or aesthetic — to make the project more than an arbitrary digitalization of one’s research interests. And while many of the week’s readings and demonstrations of digital tools contributed to an atmosphere of limitless possibility, perhaps it is naïve to think in terms of a vast sea of lost texts that would be best served by preservation as digital editions or databases. Maybe Dean’s ideas about beginning a process of recovery and leaving open the possibility of walking away are relevant not only for projects involving sensitive Indigenous texts; perhaps truly responsible editing practices have to involve a surgical use of well-selected technologies for carefully thought-out purposes rather than be based on enthusiasm for the possibilities opened up by emerging digital technologies. I’m the kind of person who frets about most things, but last week’s discussions have nevertheless encouraged me to think more deeply about how to proceed with my edition.

Thankfully, however, these worries dissolved in waves of screen prints and sushi and seasonal beverages, not to mention the literal waves of Okanagan Lake. Much as my brief swims provided valuable respite from the patrons of the Centre of Gravity music festival (see also: the Bro-nado), I hope my use of digital editing methods results in a useful, if necessarily modest, final product.