Archives

Author Archive

October 14, 2014

Writing in Canada Digital Publication and Conference

More new content on the George Whalley website!

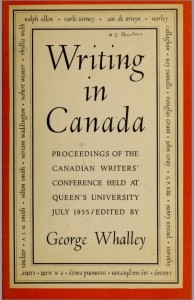

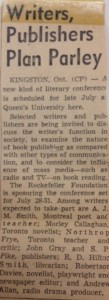

It’s with pleasure that we’ve now made available on the Whalley site a digital copy of Writing in Canada, George Whalley’s edited proceedings of the prestigious Canadian Writers’ Conference held at Queen’s University in July 1955.

The 1955 conference was a veritable who’s who of writers in Canada, with delegates including Earle Birney, Desmond Pacey, Eli Mandel, Anne Wilkinson, Dorothy Livesay, Hugh Garner, James Reaney, Jay Macpherson, Phyllis Webb, Adele Wiseman, Ralph Gustafson, Douglas Spettigue, Miriam Waddington, Irving Layton, Frank Scott, Louis Dudek, A.J.M. Smith, and Morley Callaghan.

Writers and critics were brought together at the conference with publishers, journalists, and interested members of the public to investigate a number of common concerns with writing in Canada, from concrete problems like a lack of contemporary Canadian poetry in school texts and a need for cheap editions of Canadian works to broader questions about what people read in Canada, whether criticism is beneficial to writing, and the impending obsolescence of the book form. All of these questions have echoed throughout Canadian literary history; Editing Modernism itself is part of a movement towards remediating the issues of access to Canadian books identified in 1955.

As Douglas Fetherling observed in the Kingston Whig-Standard in 1988, the conference took place at a decisive moment in Canadian cultural (and especially literary) history, with the Massey Report fresh off the press and the Canada Council just over the horizon. “To the delegates attending the Kingston conference,” writes Fetherling, “the future was of course unclear. But they appeared to sense that they were standing on a threshold. It must have seemed that anything was possible.” This sense of possibility permeates Writing in Canada, as does the intensity with which various means of fulfilling it were advocated—an intensity that led Whalley to describe conference discussion as a kind of “extreme literary criticism … in which the various branches of literature attacked each other unmercifully and accused each other of all kinds of crimes and fancies, some of them unmentionable” (Writing in Canada MS, QUA).

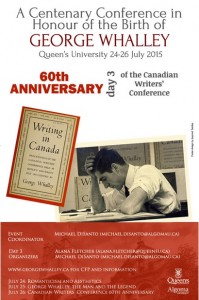

Writing in Canada’s reflection of this influential and highly-charged moment in Canadian literary history is must-read material for anyone interested in the direction of literary production and the cohesion of literary community in Canada. It is an especially apt historical touchstone to consult in the run-up to 60th anniversary of the Canadian Writers’ Conference taking place this coming July at Queen’s University.

We hope this meeting, which is part of a larger three-day conference held in honour of George Whalley’s centenary, will revisit some of the issues of 1955 in a contemporary context with an intensity to rival that of ’55.

Find the full text of Writing in Canada here and the call for papers for the 60th anniversary of the Canadian Writers’ Conference here. And don’t forget to get your conference paper proposals in to us by October 31st!

October 9, 2014

Death in the Barren Ground

We here at the George Whalley project are pleased to announce the availability on the George Whalley website of a section of one of Whalley’s most riveting broadcasts, “Death in the Barren Ground.” This 30-minute audio drama was aired on CBC radio’s Wednesday Night on 3 March 1954, and was re-broadcast on the same program in June 1954, by CBC’s International Service in December 1957, and on CBC’s The Human Condition in April and June 1967. It appeared on television over still photographs on CBC’s Explorations on 28 October 1959, and was repeated in this form on CBC TV’s Q for Quest on 6 June 1961. It is one of the many professional broadcasts Whalley prepared for the CBC between 1953 and 1971, the full bibliography of which can be found here.

“Death in the Barren Ground” tells the dramatic story of the last journey of John Hornby (1880-1927), an English explorer best known for his travels in the Northwest Territories. The story begins with the discovery of the bodies of Hornby and his travelling companions Edgar Christian and Harold Adlard—all of whom, as the CBC Times description puts it, “died slowly and painfully of privation … in what explorer Samuel Hearne called ‘The Barren Ground’”—by a party of geologists traveling the Thelon River in 1928.

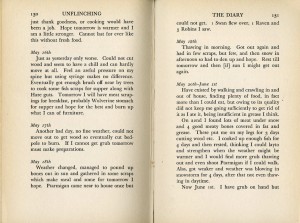

The drama unfolds on a framework provided by Edgar Christian’s diaries, which were found in the stove of the ill-fated party’s cabin on the Thelon. These diary excerpts carry the bulk of the narrative, with a narrator and some invented speech from both Hornby and Christian filling it out. A number of other important historical documents are woven throughout: a diary of Hornby’s (reported in Christian’s own), Hornby’s will, unsent letters from Christian to his parents, and the 1929 report of the G-division commanding officer of the RCMP on the burial of the bodies and the collection of the documents.

Whalley’s interest in the last journey of John Hornby and in Edgar Christian’s role as its de facto historiographer was longstanding. In 1962, Whalley would publish a biography of Hornby, titled The Legend of John Hornby.

This was the first published text to include the letters Christian wrote to his mother and father as he was dying, in which he implores “Please don’t blame dear Jack.”

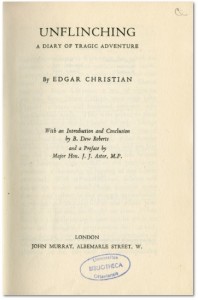

In 1980 this biography was followed by Death in the Barren Ground: The Diary of Edgar Christian, a newly edited version of Christian’s diary, which had previously been published in 1937 as Unflinching: The Diary of Edgar Christian.

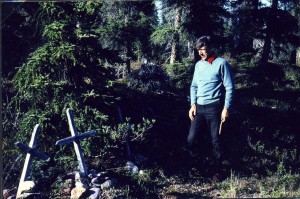

Whalley’s reading of the 1937 Diary was the inspiration for the radio and television broadcasts, as well as his later work on Hornby and Christian. In 1971 Whalley took a trip to the Hornby cabin and visited the sparsely marked sites where the bodies of Hornby, Christian, and Adlard are buried.

Find the full audio version of “Death in the Barren Ground” here. In this version from CBC’s Wednesday Night, the narrator is Frank Paddy, Edgar Christian is played by Douglas Rain, John Hornby by Alan King, and Inspector Trundle by Jim McRae. Happy listening!

June 8, 2014

Tool Tutorial: Out-of-the Box Text Analysis

This year at DHSI — my third and perhaps last round of it — I took Out-of-the-Box Text Analysis for the Digital Humanities, taught by NYU’s David Hoover. This class deepened my understanding of the way digital tools can enhance traditional ways of reading and analyzing texts. Using the Intelligent Archive Interface (a text repository developed at NYU and downloadable at http://www.newcastle.edu.au/research-and-innovation/centre/education-arts/cllc/intelligent-archive), as well as Minitab, Microsoft Excel (with a number of additional macros from Hoover), and some basic TEI, we explored largely comparative ways of answering questions about authorship attribution, textual and authorial style, and meaning, based largely on word frequency. The results of these analyses were visualized using dendrograms, cluster graphs, and loading/score plots.

Here’s a walk-through of one of the basic methods we learned of creating and visualizing a comparative analysis of the most frequently-used words in different texts.

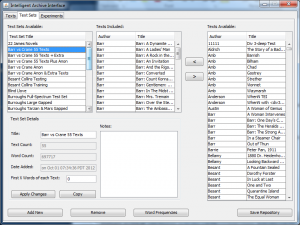

First, open the Intelligent Archive. In our class, we used a version populated with a number of plain-text novels, short stories, and poems edited by David Hoover. Go to “Text Sets” and either select an existing set of texts to compare, or create a new set. To create a new set out of new texts, go to the “Texts” tab, “Add New,” browse for your file(s), and add them to the repository. Give your new text set a title and add your new texts to it using the left-pointing arrow. Here, texts from 19th-century authors Stephen Crane and Robert Barr are being compared under the text set title “Barr vs Crane 55 texts.”

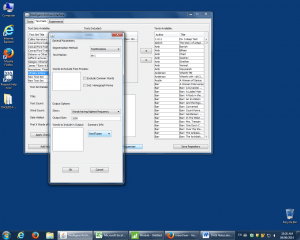

Once you have the text set ready for comparison, click on “Word Frequencies,” and choose the proper parameters for your comparison. Different selections provide slightly different results: the “BlockBigLast” selection divides the text into chunks and places any extra in one last large chunk. You can also select “Text Divisions” if you’ve marked divisions (ie. for chapters) in the plain text file you’re working on. Choosing “Text” will simply compare the entire texts against one another. “Words Having Highest Frequency” is the selection for charting the most frequently-used words across the indicated chunks of text. Other possible selections are “Inclusion words” selections (sorted or unsorted): entering particular topical keywords that you’d like to track in the “Words to Include in Process” box includes only these keywords in the analysis. The output size is the number of most frequent words (or least frequency words, or words with highest hits [that is, words occurring in most sections of the text, but not most frequently overall]) you’ll be using. 1000 is the highest word count that can be used in Minitab. Finally, select “WordTypes” to make sure you’re analyzing words.

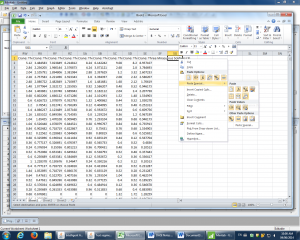

Once you’ve made your parameter indications, click OK. This will generate a text segment list, which displays the number and proportion of times the most frequent words occur in same-size chunks of each text.

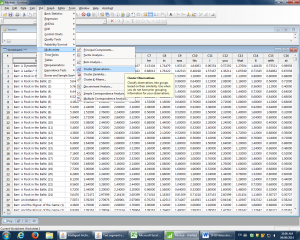

Change the output type to “Show Proportions” (this gives you the percentage occurrence of word frequencies). Select all the data with the “Select all” button, and then click on “Copy to Clipboard.” Next, paste the segment output into a plain Excel spreadsheet, transpose it so that the texts run down the side and the words across the top; and run a find and replace to change any apostrophes to carats (apostrophe seem to throw things off).

Copy this transposed spreadsheet into Minitab.

In this new Minitab worksheet, go to “Stat” in the toolbar, choose “Multivariate,” and then “Cluster Observations.”

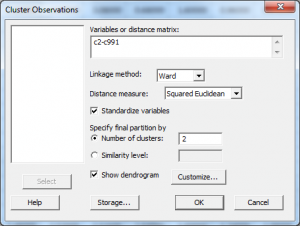

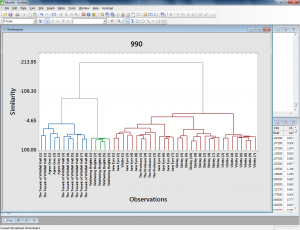

Under “Cluster Observations,” set the parameters to measure as many of the words as desired (words are listed down the left-hand side; these disappear once the range is selected). For example, c2-c991 captures the 1st to 990th most frequently used words. Select “Ward” as Linkage Method, “Squared Euclidean” as the Distance Measure, and click “Standardize Variables” and click “Show Dendrogram.” The cluster number should be appropriate to what is being compared; here, there are two authors being compared, so I’ve selected two major clusters.

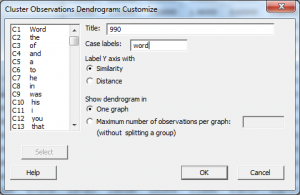

Under “Customize,” give the dendrogram a title, and put in “word” as the case label. Here, the title indicates the measure of 990 most frequent words.

Click OK and OK again and the dendrogram appears. If desired, right-click on the titles along the bottom and go to “Edit X Scale” to make the font smaller, and change the alignment to 90 degrees for easier reading.

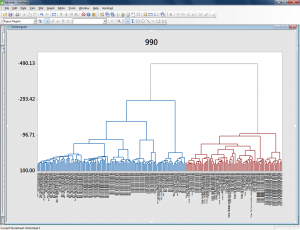

This dendrogram visualizes a comparison in which all the Barr texts group together in the blue cluster, while all the Crane texts groups together in the red cluster. This means that these two authors can be easily distinguished based on the most frequent 990 words they use.

In this example, a similar analysis of a number of texts by the Bronte sisters reveals that certain parts of their novels group with one another stylistically. The beginnings of their novels are especially similar — often, beginning sections are more similar in terms of word choice to other beginning sections of other novels than they are to the rest of the same novel.

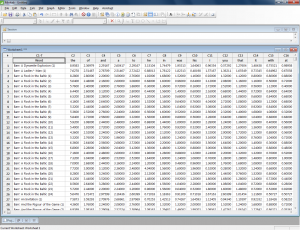

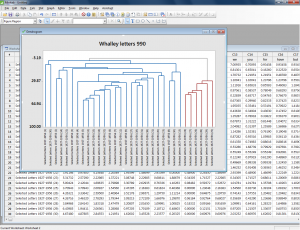

I also used this tool to measure the most frequently-used words in approximately 30 randomly-selected letters George Whalley wrote to his family between 1927 and 1956. In this case, I created a plain text file of all the letters, divided into individual letters using simple TEI headings. I indicated in the text set dialog that I want these divisions to be compared by selecting “Text Divisions” under Segmentation Method and inputting the division type (I only used one type of division to divide each letter, so I chose div1).

Then I followed the steps of changing the text segment display mode to proportions, selecting it all and copying to clipboard, pasting into Excel, transposing, replacing apostrophes with carats, and copying and pasting into Minitab. I used the usual parameters for Cluster Observations display.

The resulting Whalley dendrogram shows that a certain period of letter-writing is definable as using words differently than the others. These are a group of letters later in Whalley’s life (letters 24 to 29 of 31); however, the two letters that follow these are grouped with earlier letters (letter 30 is most closely aligned with letter 1, surprisingly, and letter 31 aligns most closely with letter 19).

I’m not quite sure what, if anything, to conclude from this visualization. It seems to me that this particular tool can be useful in indicating differences in style that need to be explored further through more traditional methods like close reading and research into historical context – for example, maybe a particular project Whalley was working on in the 1950s made its way into a number of letters. The dendrogram/word frequency analysis doesn’t show us this, but could point us towards it (if we didn’t already recognize it through reading the letters).

I would most recommend a tool like this for exploring authorship attribution or for very preliminary exploration of how certain topical keywords are used across a body of work. David Hoover is extremely well-read and a wonderful instructor, and I would also recommend his class to anyone interested in that kind of work.

Another DHSI, another tool learned!

March 7, 2014

Draft 1, Draft ?, Draft ?: Editorial Notes and Nuisances

So, as some of you may know, for the past year and a half I have been working with Michael DiSanto on the George Whalley digital edition, the basis of which is a huge Whalley database. The first year was a serious learning journey filled with reading, training (DHSI!), planning, scanning, scanning, and more scanning, editing, uploading, describing, and transcribing. Now, the Whalley database has been migrated to a spiffy new website designed by Robin Isard, and we are really moving toward our digital edition. What I’ve been doing for the last several months is writing editorial notes for the poems we have selected as definite inclusions for the edition: “Elegy,” “Battle Pattern,” “Calligrapher,” “Pig,” “A Minor Poet is Visited by the Muse,” “Lazarus,” “Letter from Lagos,” and “Dionysiac.” Each note has ended up between 1500-3000 words, depending on how involved Whalley’s revision process was. Each one includes certain common elements: a description of the number of extant texts and their pages in manuscript and typescript, the publication history, a chronology of the versions, and any relevant biographical details (some of these are pretty fun, like the fact that “Pig” was inspired by a pig footstool Whalley bought in London).

Determining the chronology of documents has guided my writing of these notes, as I personally find the way the text has morphed from one version to the next over time to be the most important element of defining the revision process for a user. I begin by consulting the timeline of poems created for the project by “research assistant extraordinaire” Stacey Devlin, to make sure I don’t miss any documents corresponding to revision dates already identified, and then consulting the timeline of Whalley’s life to confirm where he was and what he was doing while writing the poem. Then I scour the database, checking in the relevant record container for all versions of the poem and using the search function to find related documents (pictures, audio recordings, etc). I jot down the titles of all the documents, with dates (if available), brief descriptions, and item numbers, and confirm that I’ve got all the dates recognized in the timeline covered (or make notes of which ones I’m missing!). Then the tough part starts—which version comes when? To start, I use the dated documents (there are always a couple of these, thanks to Whalley’s organizational foresight) to create a skeleton revision outline, then add tentative works to it based on their titles, placing together, for example, all the drafts titled “Resurrection Stone,” and all the ones titled “Lazarus.” When a document is untitled, we title it using the first line, so I can group these together too. Working with these smaller groupings, I then compare the works against one another line by line, making note of where handwritten revisions and marginal notes have been incorporated, where changes apparently not indicated by revision marks occur, and where one base text corresponds to another. I re-group, un-group, and group the versions again, and connect the groups to one another. This part of the process, where I compare different versions and note revisions, looks something like this:

As you can kind of see in the notes, the revisions I’ve recorded in the top draft are incorporated in a draft I’ve called “RS3” for short (“Resurrection Stone [3]”), and I’ve discerned that this draft is spread across multiple one-page records. I also use a whole slew of less technical aides, including the old post-it note page tracker, handwritten timelines, and the odd napkin collation (it’s the poor man’s Juxta!).

By the end, I’ve got a firm grasp of what I think the chronology is, and why, and can pinpoint particularly illuminating instances of revision for the reader of the editorial notes.

The images above are taken during my writing of the editorial note for “Lazarus,” which has been the most involved one yet (edit: not as involved as “Dionysiac,” which was printed in two separate versions and has only one real cross-over version!). I often feel very lucky to work on someone as organized as Whalley, who dates his drafts often and uses reasonably legible proofreading marks. One of the most confusing things about discerning the order in which various pieces and drafts of “Lazarus” were produced, though, is that Whalley seems to have flip-flopped a number of times on some things—on one draft he’ll change a certain word, phrase, or line break, and he’ll incorporate this change in the base text of another draft, and then in the next draft it’ll be back to the way it appeared before! One example of this is the way Whalley worked on the poem without, then with, then finally without its first stanza. A smaller and more tedious instance of this is his back-and-forth over what would become line 30 in the published poem, which appears as “He claws his way out of the undertow,” then “Out of this undertow he claws his way,” and back again, and back again, several times.

To be honest, I’m really enjoying writing these notes. I get unreasonably excited about discovering sources of Whalley’s inspiration, even if I can’t figure out how they’re being used—for example, there’s a marginal note on the very first draft of “Lazarus” that reads “See V. Woolf ‘On Not Knowing Greek.’” I took a fair stab at explaining this, but I’m still not totally sure what the connection is. A more obvious source of inspiration for “Lazarus” is the sculpture of that name by Jacob Epstein, the posture of which is the focus of Whalley’s early drafts of the poem.

This is probably quite an idiosyncratic “how-to” for editorial notes, but I hope it was illuminating in some way. I would welcome any tips and tricks from veteran editors on how to polish my approach!

August 23, 2013

A Year of Whalley

Since May of 2012, Michael DiSanto (Algoma University) and I have been collaborating on an open-access, online database of primary materials that includes scans of Whalley’s poetry manuscripts and typescripts, related letters, personal papers, and photographs. The database, which was adapted from the Algoma University Archive (AUA) and the Shingwauk Residential School Centre, built by Robin Isard, the eSystems Librarian, and Rick Scott, the Library Technologies Specialist, is connected to the open access website Michael edits and manages, www.georgewhalley.ca. The database is RAD (Rules for Archival Description), OAI (Open Archives Initiative), and Dublin Core compliant. This means the materials collected by the project can be easily moved into almost any library or archival database via OAI protocols. With the cooperation of the Queen’s University Archives (QUA) and the Whalley estate, the database is used to collect Whalley materials together in one location and make them accessible from anywhere on the internet. This database will serve as the foundation for subsequent digital and print editions of Whalley’s works, the first of which is a digital edition of selected materials that will provide rich insights into George Whalley’s creative process as a poet. This digital collection will serve as the counterpart to the scholarly print edition of Whalley’s collected poems that Michael is editing for McGill-Queen’s University Press (MQUP), with an expected publication date of 2015. The digital edition will be comprised of manuscripts and typescripts, as well as private papers such as the composition calendar in which Whalley recorded the dates and locations he composed and revised many of his poems between 1937 and 1947. Whalley’s letters from his correspondence with Ryerson Press for the chapbook Poems 1939-1944 (1946) and selections from his wartime correspondence will also be included, and transcriptions for each digital image will also be presented.

My work on the Whalley project has provided me with valuable experience working first-hand with the very rich collection of published and unpublished materials in the QUA’s George Whalley Fonds. I spent much of my time during the last year scanning letters and poetry and prose manuscripts and typescripts located in the QUA to digital archival standards (between 400 and 600dpi) in TIFF format, editing them, converting them to JPEGs, and uploading them into the database with RAD-compliant descriptions. At the same time, Michael has scanned, edited, converted, and uploaded documents in the private papers kept by the Whalley family in Southwold, England, and by various other people connected to Whalley. Between the time I joined the project in May 2012 and the end of March 2013, we made 1711 records describing 4888 files, including no less than 4075 pages of manuscripts, typescripts, journals, and letters. Both Michael and I have also produced public works on Whalley. I presented a conference paper at Trinity College Dublin in mid-June of this year on Whalley’s multi-linguistic radio adaptation of Primo Levi’s memoir, Se questo è un uomo, and made a colloquium presentation at Queen’s University which compared the self-presentational modes of Whalley’s pre-war, wartime, and post-war letters to his mother. Michael, Robin, and I also gave a talk on our approach to the Whalley project entitled “Archiving from the Start: An Archive Database Solution for Literary Research” at DHSI this past June.

Currently, we are working with Robin on a major refresh of www.georgewhalley.ca and on formulating the technical and aesthetic design elements of the edition. Some of the editorial decisions we have made concerning the edition include the choice to use a “Related Materials” sidebar to direct users to documents connected to the one they are currently viewing. My work has shifted in the last month to focus on editing the database’s records for various typescripts and manuscripts into a more granular format, to enable users to search quite specifically among records.

December 6, 2012

Oh, the Irony!

This is a relatively short note about something that has been nagging at me for some time. Over the course of the first part of my EMiC-funded project – to digitize and create a database of the poetry, prose, essays and life writings of George Whalley – I have learned a great deal about editing for an edition, and specifically about the ways in which the digital environment facilitates versioning. It has occurred to me over the course of my work and while attending various conference panels on digital editing that perhaps we, as digital editors, are less attuned than we should be to recording the genesis of our own projects for institutional memory. The process of putting together a digital edition seems potentially endless. Whalley’s writings could easily take a lifetime to collect, digitize, and describe, let alone tag in TEI, explicate and annotate, and visualize using visualization tools. I wonder whether there is any sort of protocol for recording our editorial choices for the next person who takes up work on the author we are working on, or whether siloing and/or lack of such protocol dictates that scholars newly approaching the subject lose out on all justifications of the hard work done before, and have only the finished product from which to infer method. I think the issue of erasure of the “versions” of a digital versioning project is immediately relevant in light of the rapidity with which digital technologies are changing; if versions of a project could be saved as the project advances, it might be easier for future scholars to decipher (and repeat or diverge from) the modus operandi of their predecessors when attempting to migrate the final version to an updated information management platform.

What do people think of this? Is there a way to record the steps of digital production as there are on paper? Or are we stuck with the final product? Are we at risk of losing the justification of our work due to the erasure of genesis markers online?

June 8, 2012

Tenure Lack, Alt-Ac, and Generally Talking Back

Throughout this week (my first DHSI!) the lack of tenure-track positions for those currently graduating with doctoral degrees was a major topic of discussion. In personal conversation with wonderful EMiCers and non-EMiCers alike such as Kersta, Melissa, Emily Ballantyne and Emily Sharpe; Alyssa Arbuckle, Sandra Parmegiani, and Caley Ehnes; and Donna Bilak and other new acquaintances at the Institute, dissatisfaction with what Daniel Powell called “the straight and very narrow path” on which academics are set today was palpable. Wednesday’s unconference session on Alt-Ac, DH, and Graduate Training (organized by Powell, Alyssa Arbuckle, Alyssa McLeod, and Shaun MacPherson) provoked denigration of the narrow track from graduate programs geared too exclusively towards the acquisition of pedagogical, professional, and methodological practices necessary for that specific but oh-so-elusive tenure-track position. This particular session focused on restructuring graduate programs as a method of providing academics with more transferable hard skills and thus a wider individual arsenal with which to tackle job market, both Ac and Alt (as in Ryerson’s Literatures of Modernity program – http://www.ryerson.ca/graduate/literatures/. See full notes from the unconference session here: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1CKuRYHE7D157D6vHrLmySwCPX4ViHD_G6OaAvM1h86k/edit?pli=1). But for me the format of the session itself was the most effective answer to the problem at hand: the meeting provided a timely platform for the type of preliminary autogenic and collaborative work which is, in my view, the best response to a decaying hierarchical structure of academic competition and intellectual siloing. I thought the session, in which graduate students and recent graduates defined their own concerns, articulated their desires, and identified existing models on which to build, was a succinct example of how the soft skills of collaborative brainstorming, crowd-sourcing, large-scale trouble-shooting, and project planning learned in DH can be practically applied to change the largely unsatisfactory existing structures of graduate training and academic opportunity.

With so few tenure-track positions currently available – especially teaching Canadian literature in Canada – it is clear that academics need to create their own opportunities outside the traditional walls of the academy. My experience and discussions this week have solidified my belief that not only is this creative self-sustenance a necessity, but, especially for those in the digital humanities who have been part of collaborative and innovative digital initiatives, it is a very realizable possibility. I think we should look at this dearth of access to traditional, well-defined professional “tracks” which may suit our skill sets but not necessarily our research interests, personalities, or lifestyles less as a major professional concern enhancing collegial competition, as this view leads to further entrenchment of departments in traditional disciplinary models as various fields attempt to protect their practices from interdisciplinary dilution. Rather, the inevitable breakage of this archaic system can be viewed more as an opportunity for junior academics to identify our own individual niches, point them out, and fill them. While this seems idealistic, such examples of collaborative initiatives for intellectuals outside or in partnership with the academy can be found close at hand in DH: the Modernist Commons in which the Digital Editions class has been working this week is one of many examples in DH of autogenic scholarly creation – born, of course, of the mother of necessity. Specifically literary endeavours for academics include Ooligan Press’s Graduate Program, which provides MA and MS degrees in book publishing in partnership with Portland State University, is a student-run press which publishes in both print and digital media (http://ooligan.pdx.edu/graduate-program/); while initiatives like the independent Netherlands-based think-tank Kennisland (http://www.kennisland.nl/en) provide a model for larger and more interdisciplinary (quasi)-Alt-Ac involvement. The more doctoral graduates with experience in DH use their experience in collaborative project planning to plan and build the career they want, the less legitimate the current “one-track-fits-all” mentality will become, and the pressure felt by those within graduate studies to compete with one another to support existing, unsatisfactory structures may be replaced by the impulse to collaborate and create new ones.

Examples of successful Alt-Ac projects, suggestions for new ones, and ideas for funding are welcome!