Community

December 7, 2015

The Unbearable Lightness of Archives: Re-launching the bpNichol.ca Digital Archive

by Gregory Betts

With the sole exception of the audio recordings, the recently relaunched bpNichol.ca Digital Archive is a collection of photographic images that stand in stark contrast to the print-medium objects they represent. We have, then, a medium translation into the symbolic regime of the archive, where data (in fact, the texts that Nichol produced and published) are isolated into discrete series in order to open them to different configurations. Despite the gregarious warmth of bpNichol, Canada’s preeminent avant-gardist—indeed, our own “Captain Poetry”—the archive flattens the lush sensuality, the intricate materiality of his works into two-dimensional images, digital files that are represented entirely by light patterns on a smooth screen. Media archaeologist Wolfgang Ernst highlights such a “cold archaeological gaze” as “the melancholic acknowledgement of the allegorical gap that separates the past irreversibly from the present, a sense of discontinuity, as opposed to the privileging of continuity in historical narrative” (44-5). The digital archive encodes this separation without demanding a binding historical narrative. These are the things, separated from their aura as Benjamin would note, reconstructed in order to maximize access and circulation.

Nichol’s oeuvre, with its enormous scale and variety, represents an archive of limit-cases of Canadian small press publishing techniques and technologies. The two-dimensional digital files, however, efface some of the most striking characteristics of these often handmade objects, produced as they were in micro, sometimes single-digit, print runs, and often made for or given personally to a specific person. Nichol was a communitarian, and used his literature and publishing ventures to create and foster avant-garde communities. They are consummate exemplars of ephemera. As such, they performed a kind of exclusive communitarian function that contradicts open source digitalization: these were not intended to be objects of simultaneous collective reception. They are now, though, in this remade archived form.

The re-launch of the bpNichol digital archive thus serves as the institutionalization of a new phase of engagement with Nichol’s work that shifts beyond the direct impression of the biological author. This shift was evident at the 2014 bpNichol symposium I organized at Brock University in St. Catharines called “At the corner of mundane and sacred” which featured 16 paper presentations, 20 poets reading work inspired by bp, and hundreds of people on twitter doing an online flash mob of their favourite lines and puns from his work. It had the air of a celebration and it felt vital. We were lucky to have some of bp’s closest friends, colleagues, and collaborators presenting, including Steve McCaffery, Stan Bevington, and Stephen Scobie, but what was most striking about the event was the presence of new generations and their investment in thinking upon his works and discovering new ways to manifest his spirit of investigation, sincerity, and generosity. These are the sons and daughters, grandsons and granddaughters of Captain Poetry. Without ever having met the man, they have already begun building their own bps.

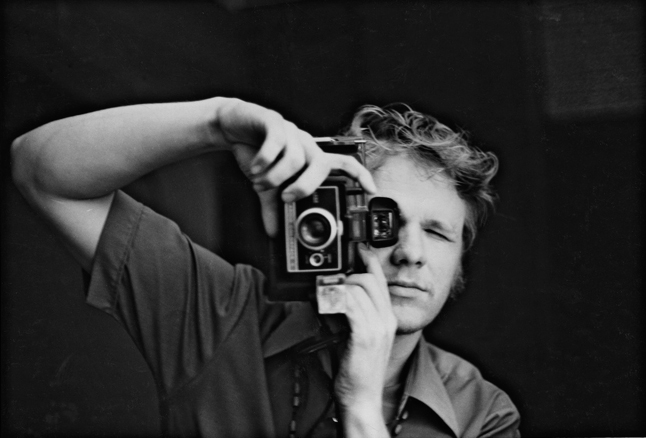

One such builder is filmmaker Justin Stephenson, who was at the conference to show us a glimpse of his new bpNichol film called The Collected Works in advance of its Toronto premiere. Functioning as both a dynamic archive and creative work in its own right, Stephenson’s work translates Nichol’s poetry (not his biography) into a dance of light and sound. Ernst notes that the photograph offers a distinct kind of representation of the past as it inscribes chemically and/or digitally the physical trace of the past. As such, the photograph “liberate[s] the past from historical discourse (which is always anthropomorphic) in order to make source data accessible to different configurations” (48). Stephenson’s film ruptures “the illusion of pure content” by his creative interventions in the re-staging and selection of Nichol’s work. Similarly, the bpNichol.ca digital archive encodes self-reflexivity by documenting the time, date, and (where available) technology of digitization as part of the meta-data record for each object in the archive. There are, of course, three time signatures at play in each photograph: the content, Nichol’s work, the interface, our photographic rendering of them, and the intraface, the archive frame itself.

The narrative of Nichol’s first poem, the beginning of the complete works, anticipates these problems and possibilities. A student at the time in Vancouver, he wrote the poem while visiting his brother in Toronto in the summer of 1963. He was working on a normative translation of Guillaume Apollinaire’s modernist masterpiece “Zone” when all of a sudden the sun struck his page as the cars whizzed by and the sight of bodies browning in a park below his window transported him for an instant into what he felt was an experience of perfect synchronicity with the poem. Apollinaire’s 1913 poem presents a fragmented collage of a flâneur walking the streets of Paris, moving out across Europe, and recording the modernist shift of that moment. Powerful new technologies—the airplane, the automobile, electricity—were supplanting mythology and nature, but a new kind of communion, a new kind of culture, indeed a new kind of individual was emerging in the shift. Nichol abandoned his straight translation of “Zone” and wrote a short lyric about the experience of being transported by Apollinaire in Toronto sunshine: a poem of the play of light and its historical trace! His poem was called “Translating Apollinaire” and it was published in 1964 in Vancouver in bill bissett’s new magazine Blew Ointment. The somewhat diminutive work launched a career of investigation into the question of what happens when writing, poetry, language move into new, hitherto unimagined spaces; what happens when new interfaces are used to transpose historical residue.

Apollinaire’s poem begins at the end with the lovely line, “In the end you abandon the ancient world.” Nichol’s first published poem begins with Icharrus, the myth hubristic human ambitions of transportational technology:

Icharrus winging up

Simon the Magician from Judea high in a tree,

everyone reaching for the sun

great towers of stone

built by the Aztecs, tearing their hearts out

to offer them, wet and beating

mountains,

cold wind, Macchu Piccu hiding in the sun

unfound for centuries

cars whizzing by, sun

thru trees passing, a dozen

new wave films, flickering

on drivers’ glasses

flat on their backs in the grass

a dozen bodies slowly turning brown

sun glares off the pages, “soleil

cou coupé”, rolls in my window

flat on my back on the floor

becoming aware of it

for an instant

Nichol revisited this poem almost a hundred times in the years that followed, creating a series of translations that he published as Translating Translating Apollinaire. The series broke apart and rewrote this poem with the ambition of uncovering every conceivable means that a translation he could be produced. It is wild, radical research and it demonstrates Nichol’s commitment to writing not as the creation of discrete beautiful objects, but as a process of engaging with the world, of investigation, of learning, ultimately of opening oneself up to the Other; as a dynamic processing of the past. Building from this template, the archive is best thought of as just another conceivable means of translating bpNichol’s complete works.

It is, at present, a growing repository of Nichol’s work all available for free because of the enormous generosity of Ellie Nichol. There are over 100 items currently digitized in the space, thousands of pages of work, with hundreds more books and chapbooks to come. The website was designed and built by Bill Kennedy, with the enormous support of Alana Wilcox, Editorial Director of Coach House Books, and assisted by EMiC-sponsored Research Assistant Julia Polyck-O’Neill. I am the curator of the space and would like to invite you all to get involved in expanding the archive (if you are interested, click on “contact” and send me a note) because even though the digital file violates the spirit of the original (I am reminded of Jean Mitry’s quip that “To betray the letter is to betray the spirit, because the spirit is found only in the letter” (4)), the desire for opening avant-garde community spaces and engagement through this work remains.

Works Cited

Ernst, Wolfgang. Digital Memory and the Archive. Minneapolis: U Minnesota P, 2012.

Nichol, bp. “Translating Apollinaire.” Blew Ointment. 2.4 (1965). Np.

—. Translating Translating Apollinaire. Milwaukee: Membrane Press, 1979.