Community

March 27, 2015

Legends of Vancouver: Collaborative Learning (and Putting Ethics into Practice)

Greetings, EMiC community!

At nearly two semesters into my PhD at Simon Fraser University, I have some exciting research updates to share. For the 2014-15 year, my EMiC PhD Stipend project proposed to analyze and digitize E. Pauline Johnson and Chief Capilano’s Legends of Vancouver (first published in 1911).

My stipend project began with many, many hours spent in SFU’s Special Collections library. With more than 50 copies of Legends in its holdings, SFU boasts an impressive collection that spans over a century of publication.

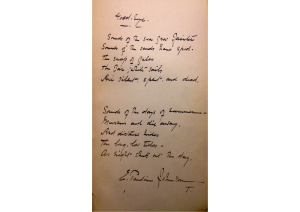

One of the most interesting parts of my research thus far has been investigating unique inscriptions and markings found in earlier copies; these paratextual elements situate Legends as a site for both remembrance and memorialization. In earlier editions of the text (those published between 1911 and 1913, while Johnson was still alive), some copies contain additional inscriptions penned by Johnson herself. In one case, Johnson makes the poignant exchange of the poem “Goodbye” as compensatory for the book’s shoddy construction: “this book seems to be rather badly put together so – I have written out a poem on the back flyleaf to ‘even things up’ – EPJ”.

In this poem, Johnson alludes to the passage from day into night as a metaphor for the transition from life into death. Her decision to inscribe this poem in 1912, only months before her eventual death from breast cancer, is curious. The poem is also significant in regards to the idea of loss – particularly as an expression of cultural mourning.

While comparing and analyzing the variant copies of Legends, I became interested in the changing paratextual apparatus and the ways in which it evinces an ongoing political and ideological series of recoveries and losses – specifically relating to Chief Capilano. Since this text was produced during the height of the socio-political movement of salvage ethnography (whereby Indigenous peoples were deemed to be on the brink of extinction), traces of these colonial power relations are present in the book’s paratext. With this anthropological trend, imbalanced power relations prevailed, often privileging the non-Indigenous voice and overshadowing the contributions of Indigenous collaborators. Early editions of this book speak to this imbalance in power, beginning with the front cover – while the generalized image of a male Chief (adorned with what appears to be Plains Indian regalia) is depicted, only Johnson’s name is listed as author. There is no mention of her collaborator on the title page, nor in the “Biographical Notice” section – and this process of erasure was perpetuated with subsequent editions. More contemporary versions of this text now include additional material about Johnson, but Capilano’s presence is still comparatively scarce (and to date, I have not seen a single edition of Legends that includes his photograph).

These observations bring me to my current research question: Why, in regards to this text, has Chief Capilano not been given the same kind of recognition as Pauline Johnson?

I am currently working in collaboration with members of the Coast Salish community to learn more about their perspectives on the Legends text. My hope is that by encouraging community dialogue and involving the descendants of Chief Capilano in this process, I can do my part to balance out the historical record. While this shift in focus strays from my initial goal of producing a digital edition, I believe that involving the community in this conversation first is necessary. After all, these are their stories.

Recently, I’ve had the opportunity to take part in an interdisciplinary colloquium and speaker series at SFU titled “Protecting Indigenous Cultural Heritage: Emergent Policy and Practice”. This series focuses on presenting new approaches to collaborative research and Indigenous policy development. As a non-Indigenous scholar working in the field of First Nations studies, this series has provided me with immeasurable insight as to best protocols for ensuring respectful collaboration. Most importantly, I’ve learned the value and necessity of putting ethics into practice. This means that my research may take more time – but I’ll be satisfied knowing that my research practices align with and reflect contemporary values regarding the protection of tangible and intangible Indigenous cultural heritage.

I would like to thank EMiC, and Dean, for giving me the opportunity to pursue this research.