Archives

Archive for November, 2014

November 13, 2014

“everythings too fuckd up today” & the revolution cannot wait: a brief reflection on the political at Avant-Canada

Not all delegates of the Avant-Canada conference would necessarily locate themselves under the umbrella term avant-garde since it is, as many critics have pointed out, a contentious, perhaps even outmoded, label with controversial militaristic connotations. However, I find the term useful in articulating a position that is not compliant with the status quo. More pointedly, the term, for me, identifies a radical mode of praxis that seeks fundamental social or political change. Avant-Canada was a meeting place for many of these types of poets, artists, and thinkers.

Continental theorists of the avant-garde such as Renato Poggioli and Matei Calinescu have addressed (with varying degrees of complexity and success) what are generally considered to be the two vectors of the historical avant-garde: 1) the radical political avant-garde, art in the service of social and political ideology; and 2) the aesthetic avant-garde, the belief that liberating artistic and literary form possesses the power to change society. This binary is over-simplified and specious, but it was while I was en-route to Avant-Canada that I wondered which face of the literary and artistic avant-garde I would enjoy over the course of the three-day gathering. Of course, it would be egregious to suggest that the conference reflected any one variant––numerous perspectives on the role of politics in art were situated, from the politically charged lyrics of the dub poets Lillian Allen, d.bi young, and Chet Singh to the more insidious formal experiments of conceptual writers like derek beaulieu and Christian Bök. From my perspective, however, the conference was characterized by a concern for topics of a more radical political interest over aesthetics.

The discussion I was privy to oscillated around topics of injustice, misogyny, and exploitation, among other issues. I am thinking of the timely “killjoy” panel “The Female Future-Garde in Canada” during which the panelists addressed issues of feminism, academia, and community by sharing not only their critical assessments, but their deeply personal narratives of experienced sexism, misogyny, and assault. The discussion was triggering and effectively confrontational––these panelists (whom I deeply admire) recognize, as Lee Maracle does in her essay “Ramparts Hanging in the Air,” that, “Silence is no longer a weapon of resistance.” Instead they vocalize a rightful opposition to the egregious offenses they face as they work to re-shape discourse, develop tactics of resistance, and strategize for the future. The roundtable left me exhausted and, as Julia Polyck-O’Neil has also indicated in her post, feeling “heavy,” but that heaviness, that weight, is something I want to carry with me as I continue to research, write, and organize to remind myself of the ways in which I can and should contribute. And I am also thinking of the dub poets, the cacophony of Jordan Abel’s plundering of Western novels in his performance of Un/Inhabited, the lucid anger of Lee Maracle’s keynote on colonialism and memory as a site of activism, Michael Nardone’s analysis of the sonic/spatial disruptions of the Idle No More Round Dance, and Skawennati’s futurist mini-series TimeTraveller™. Amongst these proceedings was my own presentation – ‘the killing of speech:’ The Sonic-Politics of The Four Horsemen” – which sought to develop a theoretical context that recovers the material and political possibilities of the sound poetry event that some sound poet practitioners have long abandoned.

The political spirit of these happenings is timely amid Canada’s ongoing climate of socio-political tumult, and indicative of a restlessness, discontent, and desire for change. It was a moment of not only broadening political and aesthetic consciousness, but the formation of a network committed to change. While bill bissett, in an apparent moment of disillusionment in 1978, once wrote “th revolushun will have to start tomorrow / everythings too fuckd up today,” Avant-Canada was a crucial interstice that saw the productive collusion of artists, activists, writers, and thinkers unwilling to wait.

November 12, 2014

Get Moving!: The Avant Canada Conference

by Kailin Wright

The Avant Canada conference (organized by Gregory Betts) fueled discussion and debates over the future—the future of Canadian art, scholarship, politics, and the academy. It was a conference that brought together scholars and artists; a conference that examined the avant garde of the pasts and futures; a conference that took me from panels on political futurity in Canadian literature, to video games, to representations of Aboriginal culture in the digital humanities, to small presses with Stan Bevington, to bp Nichol and Fraggle Rock. Personal touches like a boxed edition of Avant Canada: more useful knowledge (edited by Derek Beaulieu and Gregory Betts) and an encouraging email from Gregory Betts to the first panelists on Wednesday morning stood out, especially considering the sheer number of attendees and the scope of the conference.

I delivered a paper on failed pregnancy as a symbol of a failed national future in Canadian drama and participated in a roundtable discussion on EMiC emerging scholars. On Wednesday, I was fortunate to be a part of the “Future of Work” panel that included EMiC graduate fellow Julia Polyk-O’Neill, Robert David Stacey (Ottawa), and Carmen Derkson (Calgary); we received provocative questions on the performance of female howls as an embodied language in its own right and continued our discussion of the distinctions of gendered labor versus work late into the night

.

On Thursday, the EMiC Emerging Scholars Roundtable offered a look back at the past 7 years of the project—with all of its publications, mentorships, and training opportunities—as well as a look forward with the uncertainty of the market. Chaired by the EMiC Director Dean Irvine, my fellow roundtable discussants included Karis Shearer (UBC Okanagan), Bart Vautour (Dalhousie), and Marc André Fortin (Sherbrooke). In short, a group of scholars who I continue to learn from as they discussed Canadian poetry recordings (Karis), the Spanish Civil War project (Bart), and a daring blank edition of Barbieau’s The Downfall of Temlaham (Fortin) that performs issues of appropriation.

The conference culminated late Thursday afternoon in the spontaneous coming together of two distinct panels: one made up scholars discussing Digital First Nations and one with artists of the Dub poetry revolution. Jason Edward Lewis (Concordia), Michael Nardone (Concordia), and Stephen Foster (UBC-Okanagan) delivered work on Aboriginal territories in cyberspace, the phonopoetics of the Idle No More Round Dance Interventions, and contemporary representations of Indigenous peoples in popular culture, respectively. These papers were interlaced with performances and talks by Lillian Allen (OCAD), Chet Singh (Centennial), and D’bi Young (Independent Poet) on the political and personal in poetry. The last performer-speaker was D’bi.Young who ended the panel by performing a piece about the political shaming of female blood—a performance that took her into the audience because of, as she later explained over dinner, the sheer energy of the viewers.

This was a conference that brought you out of your seat and onto your active, political feet as you danced with artists, thinkers, readers, and activists to the sounds of Fraggle Rock.

November 11, 2014

A Thank You, A Confession, and a Digital Edition Prototype

I would like to start by thanking everyone for their cooperation over the past 14 months, during which time I pestered many of you to contribute to this blog and share updates on your EMiC projects. I have completed my term as social media intern for EMiC, and it has been a pleasure to work with all of you and see the wealth of exciting projects and valuable feedback that have been featured on EMiC’s social media outlets.

The confession part of this post is that I have not shared anything about my own (somewhat stalled) EMiC project during my time coordinating the blog. I started a digital edition project in my MA degree in 2012-13 with the hopes of having a completed website (bpnicholproject.ca) by the time I crossed the stage. The project was probably more ambitious than practical for a three-semester timeline, considering I began it with no clear idea of how I was going to get my ideas online. After realizing it would take more than a few Ladies Learning Code classes to create an interactive edition of selected bpNichol works myself, I sent out a call to Computer Science students at Dalhousie to see who I could hire as a web designer. The grad student I worked with was talented and capable, but also extremely busy with his own studies. Between our busy schedules and interdisciplinary communication difficulties (I may have learned helpful html, CSS, and JavaScript terms, but explaining the importance of bibliographic codes to a web designer is another thing), the project had a slow start. Once he finally had some prototypes for me, his server was hacked, the prototypes were lost, and he had to start over again. After redoing the pages he had previously created, he sent me all the necessary files for my own safe-keeping and politely admitted that he was too busy with his degree to continue.

Discouraged by my lack of finished product, I never really reported on these prototypes. With a full-time non-academic job, my project has been sitting on the back burner for a year and the guilt of not completing it prompted me to write posts about resources and cross-disciplinary tools but not actually write about my own project. So here is a long overdue post about where I ended up with two of the components of my digital edition, written with the hope that summarizing things “out loud” online will be the first step to setting things in motion once more.

(Pictured above is my homepage graphic that is still homeless.)

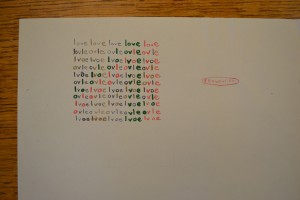

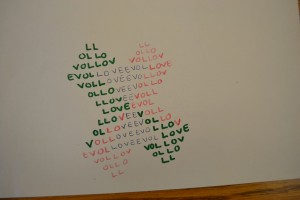

One of my main intentions with creating a digital edition (in the form of a website) of selected bpNichol works is to preserve bibliographic characteristics and the materiality of texts that are so integral to Nichol’s concrete poetry. bp often created many versions of a single work, so I also wanted to incorporate genetic criticism into my approach. Since a bibliographic editing orientation does not allow any textual features to be overlooked, genetic analyses that adhere to a bibliographic orientation must avoid creating eclectic texts, which are texts produced by collating features from all existing versions and emended to produce a copy text that includes the “best” of these features. Eclectic texts are highly impractical for concrete poetry because there is no clear way of deciding which margin width or font size is the “best” since each of these material characteristics is dependent and intrinsically linked to individual versions, their media, and the contexts of their production. In other words, each version of one of Nichol’s poems is informed by the material characteristics of all preceding versions and the significance attached to those characteristics.

While genetic criticism best directs the reader’s study of Nichol’s poems, the standard form of annotations used for this critical orientation, which refers to spelling and word use variations in a coded list ordered by line number, does not provide adequate representation on the subtle variances in bibliographic characteristics. Since Nichol includes bibliographic codes as part of his poems’ aesthetic dimensions, the materiality of his work plays a major part in the movement of his writing. Many of his poems do not vary in content between versions, but their aesthetics change due to alterations in bibliographic code.

My digital edition resists linear presentation and integrates apparatus with content by using a dynamic template to display scanned images of all versions of a chosen poem. The user can move from image to image by selecting thumbnails from a wheel or cycling through images using the arrow keys or ‘previous’ and ‘next’ buttons. The selected image moves to the centre of the wheel, allowing an image that had previously assumed the position of textual apparatus for the centre text to become the copy text of the edition. This template allows the genetic portion of my digital edition to function as a sort of version map, where the eye can move from one version to the next in an image landscape, making visual connections in all directions. The genetic narrative of the writing and production processes that can be inferred from the differences between versions can be picked up and left off at any point, thereby de-emphasizing initial intentions and end results and instead offering readers the opportunity to perceive a work from the vantage point of any one of the texts that comprise that single work. Each image acts as an annotation to the rest, providing information about textual variants just as traditional genetic endnotes would while allowing each image to function as both copy text and textual apparatus.

This screenshot shows the basic design of the version map.

This screen shot shows the version gallery after another image has been selected as the centre image.

The scanned images maintain the visual bibliographic codes of the original texts, such as font, paper colour, spacing, and margins. However, they do lose other bibliographic characteristics such as paper weight and texture, context provided by format (i.e. whether the poem is printed in a book, journal, or non-codex format), and context provided by front and back matter and placement amongst other content. Another difficulty I have encountered is maintaining page size. The web designer I worked with last year was unable to create a gallery of images that works in the way I just described while also keeping the original page sizes and still making everything visible on a standard computer screen. Even the irregularity between the shapes and sizes of scanned images causes problems of overlap when certain images are in the middle of the wheel (as shown in the below screen shot). My intentions of preserving bibliographic codes in every way possible don’t jive well with web design conventions that lean toward uniform image sizes and shapes.

I have also debated how much to provide for textual annotations. The below screenshot shows the images with no textual annotation for the centre image, with only the other images acting as genetic annotations. However, I feel that some traditional textual annotation is necessary to provide context.

The other section of the digital edition I had mapped out that I worked on with a web designer was a simple interactive section involving the text Still Water.

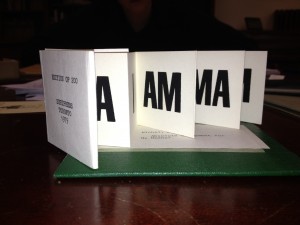

With traditional books, reader interaction is limited to turning the pages and reading the text, controlling the speed of reading but not much more. Readers could choose to read the pages out of order, but not without being aware of the definite sequence that is imposed upon the text by its bound format and page numbers. Nichol expanded these options first in his print material with works such as Still Water, which consists of twenty-eight cards in a box and could be shuffled and re-sequenced. In my digital-edition prototype of selected Nichol works, I focus on the potential to translate some of the original material characteristics of Still Water, particularly those that encourage interaction between the text and the reader, to a digital medium by making the collection available online.

This miniature archive of concrete poems printed on twenty-eight square cards in a box is difficult to find in its original form, and anthologies and critical editions that include excerpts from it lose key elements of the reader’s relationship with the text by re-printing the excerpts in a traditional codex format. Since Nichol did not number any of the cards, Still Water is not subject to any particular order, nor is it confined to a one-page-at-a-time presentation since the “pages” are not bound together. These features allow the reader to step in as editor of the text, arranging and re-arranging the poems. With no available record of the original order, readers cannot even be sure that the shape and flow of the text has not already been partially determined by previous readers. While there are cards with title, publication information, and dedication, the identities of text and paratext are blurred by such poems as “the blue pen i write these poems with,” which could be a stand-alone piece, a supplement to preceding or subsequent poems, or an author’s note about the production history of the text. Similarly, there are also three blank cards, which bear no marks to designate them as front or back matter, and which could be inserted throughout the body of the text in order to create pauses or indicate sections.

The interpretation of Still Water not only varies with its arrangement but also differs based on whether the reader views the work as a collection of individual poems or as a holistic whole comprised of parts with individual sub-narratives. The lack of binding and the perfectly square shape of the cards allow the reader to arrange them as a scene, in a four-by-seven rectangle, a two-by-fourteen column or any one of numerous irregular shapes, with juxtapositions and connections created by placing cards edge to edge. The scene can be read top-to-bottom, left-to-right, or as one large poem that draws the eye to its various quadrants and single cells based on the weight of words, groups of words, or absence of words.

Still Water re-invents the book as a collection of pages that allow content to be interpreted based on the relation of each page to all the others. With Still Water’s remediation of the book as a series of unbound cards, the authority that the book holds as a medium that directs the reader from the beginning to the end in a linear progression is transferred to the reader who can now direct the narrative flow of the text.

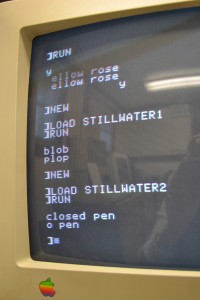

While at Lori Emerson’s Media Archaeology Lab at the University of Colorado in Boulder, I created five short programs for five different Still Water poems on the Apple IIe using Applesoft BASIC language (see above image). The programs were saved to a 5-¼-inch floppy and can be recalled by typing the commands LOAD STILLWATER1 (or STILLWATER2, STILLWATER3, etc.) and RUN. Hypothetically, if all twenty-eight units of content from the twenty-eight cards of Still Water were created as programs in BASIC programming language and saved to a floppy disk, any user could call up the “pages” of Still Water in any order that they choose. This concept is a good basis for what can be done with more complex programming language today. Using JavaScript and jQuery, it is possible to shuffle the Still Water cards. Readers can view the cards in one order and then, with a simple click, rearrange the order and re-view the content in any one of almost infinite permutations. Unlike the programs created with Applesoft BASIC, today’s programming languages also allow all twenty-eight cards to be visualized at once and dragged and dropped into different arrangements. Also, the original font, page shape, and paper colour can be maintained through the use of scanned images.

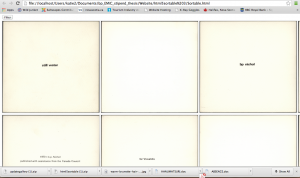

Here is a screen shot of the Still Water grid created by the web designer. One issue is that all 28 cards cannot be visible at once on a standard computer screen.

After hitting the “shuffle” or “filter” button, the cards will randomly re-order.

The reader/user can also click on individual “pages” and drag and drop them to reorder the poems as they wish.

I was generally really pleased with how this interactive version of Still Water turned out, although I admit the text can be a bit hard to read. The web designer created another html file in which the images were larger, but I find that it loses some effect as only a few images are visible in the web browser at a time.

Since the screen shots don’t necessarily illustrate the above concepts as well as I would like them to, I had hoped to be able to attach html files for you to open in your browsers, but that doesn’t seem to be possible on Word Press. If anyone would like to test out either of the components of my digital edition that I have featured here, I would be happy to email html files, and I am always happy to receive feedback. I hope to have more to share in the future as I continue to work on this project in my spare time.

November 11, 2014

Conceptual Writing and the Avant-Garde in Canada

Just days before the Avant Canada gathering in St. Catharines, the US-based journal Lana Turner published an outstanding collection of essays as part of a forum on historical and contemporary avant-garde practices and politics. In several of the 18 essays, conceptual writing is attacked directly and indirectly. David Lau, co-editor of Lana Turner, writes in the introduction to the forum that “if the avant-garde meant anything, it meant anti-capitalist, anti-status quo of the political economy,” and then details an account of “avant-garde co-optation at work in conceptual writing and the related practice of ‘curating’ digital archives of experimental art and literature.” In an important essay that problematizes race in historical conceptualizations of the avant-garde, Cathy Park Hong writes: “Conceptual writing is, for all its declarations, pathetically outdated and formulaic in its analog need to bark back incessantly at the original.” Kent Johnson constructs a conception of a “left front of the arts” from an earlier Lana Turner piece in which he declared conceptual writing “the new right-wing of the poetic ‘avant-garde.’” In this second essay, Johnson builds his argument on top of Peter Bürger’s problematic conceptualizion of the historical avant-garde, and then puts forward a simplified binary of conceptual practices that puts on one side “the heroic Chilean CADA conceptualism of the 1980s” and “the hyper-cynical, Museum-craving U.S. conceptualism of our day” on the other.

I reflected on these essays throughout the Avant Canada conference. My own paper – “On Sonic Disobedience: Phonopoetics and the Idle No More Round Dance Interventions” – put forward an argument close to Johnson’s own: “Any new ‘avant-garde’ poetics worth the historical resonance of the term will need something qualitatively more than aesthetics alone – something beyond mere prosody and theory.” Additionally, I took up Joshua Clover’s “basic orientations for a historical avant-garde in the present moment” with one edit: “One: it will not be identifiable via formal [medial] similarities to previous avant-gardes. Two: it will take as its basic provocations a set of propositions about immediate social antagonism. Three: it will draw its relation to race class gender from contemporary rifts. Four: it will align itself first with the negation of the current social arrangement including the negation of culture both as a medium for transmission and as such.” As thankful as I am for these essays, and as necessary and timely many of these critiques are for our moment, I want to offer four brief replies in regard to what I think are insufficient critiques of conceptual writing offered in the forum.

1.) Following Christian Bök’s paper at Avant Canada, I would say that those critics of conceptual writing who argue for conceptual writing’s absorption into or affinity with neoliberal politics choose to “willfully ignore” a great deal in their criticisms. Too often these criticisms buy into the persona performed by Kenneth Goldsmith at the cost of neglecting the works themselves. Often, these criticisms are most lacking in terms of what I would call a “medial blindspot,” in which they ignore the forms of textual production that are central to the diverse practices of conceptual writing: the material, technological and social infrastructures of the works, and the cultures or ecologies of their circulation. The politics of these forms of production and circulation should not be neglected in age of Edward Snowden and Aaron Schwartz. (I will leave this point perhaps insufficiently detailed at this moment, as I will be taking up specifically this project in my doctoral dissertation and hope to share excerpts of that work as I compose it.)

2.) In attempting to trouble the cultural politics of conceptual writing – which I do agree are worth troubling – too much effort is spent on what is wrong with it. Insufficient space has been taken up to think out how various tactics and strategies of conceptual writing may be useful to other (politically-oriented) practices of writing for our moment. For example, I would argue that one of the most important aspects of conceptual writing is its scrutiny of the document and its implicit focus on what John Guillory has termed “information genres.” (Here, I am echoing aspects of Darren Wershler’s paper at Avant Canada.) Examples of this scrutiny of documents have been evident in the works of Vanessa Place and Divya Victor, amongst others. In terms of the Avant Canada conference, I would say that Jordan Able’s Un/Inhabited and Rachel Zolf’s Janey’s Arcadia are two outstanding examples of how the scrutiny of documents and information genres can lead toward a potent critique and even an unraveling of settler-colonial rhetoric and discourse.

3.) I worry that critiques that set up such simplified binaries around and against conceptual writing, such as Johnson’s, reinforce what I see as a troubling narrative (too often propagated from “within” conceptual writing) that locates conceptual writing as solely emergent from a discussion of three or four (white, heterosexual) men, while ignoring the practices, discussions and publications of so many other poets. Such simplified binaries ignore Adrian Piper; they ignore Harryette Mullen and M. NourbeSe Philip; they ignore the work of CHAIN edited by Jena Osman and Juliana Spahr; they ignore Vanessa Place who has been central throughout; they ignore I’ll Drown My Book. I could, unfortunately, go on.

4.) Finally, I’d simply like to point to the generational milieu in which many (if not all) of the most polemical critiques of conceptual writing take place. What may be a clear positioning of aesthetics and cultural politics between peers of a particular (set of) generation(s) is not a fait accompli for those poets who have “come up” in the wake of conceptual writing and digital repositories such as the EPC, UbuWeb, PennSound, and Eclipse Archive. If anything, the compositional techniques, the modes of textual production and circulation, and the vast and accessible repositories of historical and contemporary works that are synonymous with or have been troublingly absorbed into the discourse of conceptual writing have significantly contributed to the breadth of effective tactics and strategies that might be taken up by future avant-gardes.

November 10, 2014

Avant Canada: poets, prophets, and revolutionaries: Thoughts on the Conference

By Julia Polyk-O’Neill

For the past three days, I’ve been attempting to take in one of the most exciting and poignant conferences I’ve ever attended. This conference, Avant Canada, held at my home institution (Brock University) and organized by my doctoral supervisor, Gregory Betts, and a committee made up, largely, of scholars I know (because of EMiC), is steeped in fascinating—and timely—discussions and debates. It has been overwhelming, but, in many ways, wonderful.

Many of the delegates are artists, poets, and scholars I have studied intensively. I volunteered at the registration desk on day one and kept doing double takes, realizing I was face to face with the human beings who produced the words I reflected on and often reproduced within my writings. The realization that these words, with which I spent such extended hours in a state of deep contemplation, came from human beings (many of whom reacted generously to my enthusiasm at connecting these proverbial dots) was initially jarring, but often throughout the week, when my mind would drift to a place of inner-calm (more on why this was necessary in a bit), I would turn this experience over anew and feel incredibly fortunate. I would return to the moment of having my paper accepted, to seeing the poster with these names, mine placed conspicuously (I felt) amongst them, and would quickly spring back to the present moment, remembering that this was special, a once in a lifetime experience.

I presented my paper on Day One, and thrilled at the reality that many of the poets and scholars I was discussing, or citing, were in the same building as I was. As the hours unfolded and my presentation time approached, a sense of calm set in. I was presenting alongside one of my EMiC colleagues, Kailin Wright, and our panel chair was none other than EMiC director Dean Irvine. I had registered the other two panelists (I volunteered at the registration table that morning), and knew I had nothing to be afraid of (if you’ve attended at least a handful of conferences, you know that there are certain things—character flaws or ‘eccentricities’—one might encounter in panel situations. Or maybe I’m just lucky). I felt pretty good about everything then, and, having made it through the presentation unscathed (with a few very good audience questions, too!), I feel great about how everything transpired.

Reflecting on my panel experience, I feel compelled to comment upon the incredible value of being a member of the EMiC community. As a relative latecomer to the project, I had the privilege of attending the final TEMiC summer institute a mere four months ago, where I met some truly exceptional scholars and enjoyed many invigorating seminars and late-night conversations at UBCO in beautiful Kelowna, B.C. We were collectively immersed in theories of textual editing, and each afternoon, enjoyed presentations by poet-scholars that related to the content of our more structured in-class discussions. Avant Canada, being a conference sponsored and organized by EMiC, brought a similarly collegial atmosphere. This suggests—and it is not an aberrant leap in logic—that there is a certain culture to EMiC-related events—one that foregrounds the importance of both the scholarly and the personal, as the events of the conference were structured according to a model that allows for much scholarly and social interaction, resulting in the creation or reinforcement of networks. When an event serves to bring together or create a mutually supportive community, even a remarkably diverse community (despite the common interest in avant-garde theory, politics, and poetics), the event and its effects become meaningful, and develops a life beyond the boundaries of its temporal and material contexts.

My panel was followed by a rather heavy roundtable, “The Female Future-Garde in Canada”, that addressed feminist strategies, as well as certain contentions within academe and publishing, and resulted, rather organically, in the sharing and unpacking of topical and triggering narratives. The evening’s keynote presentation was delivered by one of the most powerful speakers I’ve ever seen, Lee Maracle, who spoke of the grave injustices inflicted upon the Indigenous peoples of Canada and beyond, and the importance of cultural memory, and of family. I ruminated on my privilege throughout the night, at the constant joking about ‘first world problems’ that goes on between myself and my colleagues, and how, despite my fierce involvement in student politics and the growing of communities within my home institution and extremely diverse (but modestly-scaled) program, I often feel alienated, perhaps because I focus so compulsively on research and professional development, leaving little time to spend with family.

On the second day of the conference, I felt compelled to attend to some academic duties and missed Dean’s reference to some material in my paper (specifically Stephen Scobie’s work, Computer Poem, from 1968-9—and I should note that Professor Scobie was at the conference and has agreed to an interview on the topic of this under-archived work!), and when he mentioned his acknowledgement of my research, again, I felt my privilege. This was magnified during the third day, a symposium on the work of bpNichol, “At the Corner of Mundane and Sacred”, as I have been working as a research assistant for Gregory’s bpNichol project and am now, thanks to a very fancy book scanner, intimately familiar with Nichol’s work, having spent long hours struggling to scan some unusually-formatted (and quirky—as in, what is the title? Is this upside-down? How do I scan a 3D object?) texts for the archive. Coach House’s Stan Bevington’s presentation, “Small Press Workshop: Making the Avant” (with poet-cum-narrator Neil Hennessy’s often-comedic accompaniment), was particularly interesting to me, as Journeying & the returns (1967), the text he spoke to, was one of the first ‘unconventional’ Nichol texts I scanned. Bevington gave valuable context to the work’s material concerns, and the discussion that resulted from the day’s events was surreal—people exchanged Nichol (or “beep”) anecdotes and I eagerly took notes, as many in attendance did. I spent the day agonizing about all the possible mishaps that might shape my first time co-hosting a poetry reading, but nothing terrible happened thanks to an incredible support network comprised of friends and colleagues, old and new. In fact, I danced the night away with larger-than-life Fraggles.

In short, being surrounded by and engaging with mentors for a three-day period has powerful effects. Being a member of EMiC (even as a latecomer, and even as the termination of the project is imminent), and having a sense of belonging at an event like Avant Canada, was, and will continue to be, a positive and generative influence in my research and scholarly development.